“Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone.” Malcolm X.

Respect. A word most often associated with Aretha Franklin, respect can go by many other names in our society such as politeness, deference, courtesy, etiquette, reverence and obedience, to name a few. Respect is by and large considered to be a necessity in most social interactions. Even radical revolutionaries like Malcolm X recognized the importance of the age-old social nicety.

But where exactly does respect come from? While little academic research exists concerning the broad topic of respect, a great deal of theory exists concerning politeness. Sociologists such as Erving Goffman, Penelope Brown and Stephen Levinson have identified politeness as a social ritual practiced by society in order to preserve each other’s “faces” or public identities.

When we enter the public, sociologists claim that we attempt to preserve our self-esteem and our sense of independence in action. Thus, politeness is a way to circumvent any threats to these qualities. For example, in order to avoid threatening a peer’s sense of independence in action, I may ask them to “Please help me out with the group’s Prezi, if it’s not too much of a burden?” rather than demanding that they “should make the group’s Prezi.” In the latter case, the threat to independence in action is completely bare, while in the former, the threat to independence is masked by social niceties.

If we are to believe politeness theory, then this raises an inevitable question: why is it that humans are so affronted by a threat to their independence in action that they have created an entire (arguably time-wasting) linguistic system hiding these threats? Politeness theory would answer that such masking is necessary in order to ensure that all parties in a social interaction feel affirmed.

Additionally, one could argue that masked threats to independence are necessary for preserving a sense of equality in interactions. This explanation becomes more interesting when one examines various contexts in which our society requires respectful behavior.

For example, the timeless adage, “respect your elders.” Several articles have already been written concerning the various problems with this proverb, such as its inherent ageism, arbitrariness and its unjustifiability (after all, when was the last time you were told to respect your elders only once they have earned your respect?). This cultural precept requires politeness on the part of the youth, but in no way requires an equal politeness from the elder. In this case, politeness and respect are being used to enforce a social hierarchy — and as a result, it is impossible for the primary actor deferring respect to remotely believe the social interaction to be an equal one.

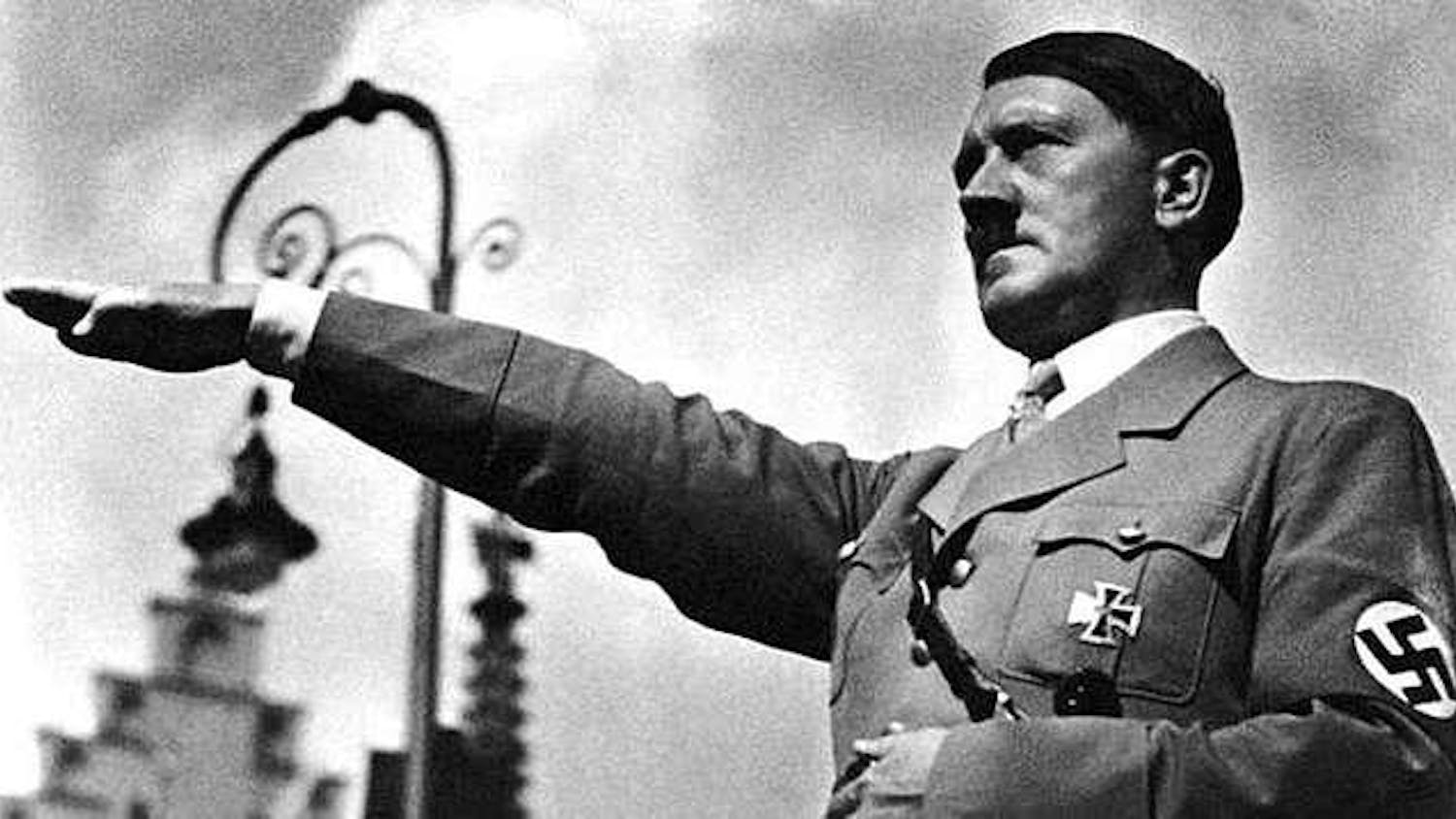

The same can be said for another common social ritual: respect for authority. As early as the first days of class, children are taught that they must always show respect to figures of authority and as children grow into adults, they pass the same message onto their own children. Our society runs on an eternal cycle of inherited, unquestioned and unjustified rules of conduct.

Perhaps it is in part due to this cycle that Americans tend to react so negatively to political activists that engage in protests or criticize figures of authority (even when justifiably so). Even Edward Snowden, a man who risked his life in order to expose governmental authority figures as significantly lacking in respectability due to human rights violations, has been widely criticized for failing to respect authority — and why? Why is it that Americans value preservation of an unjustified social nicety even at the expense of their own basic human rights?

Perhaps our society, which claims to value the equality of human beings, would benefit from an adjustment to current social behavior that arbitrarily reinforces a hierarchy. Perhaps, if humans truly need politeness to protect their own sense of independence, then citizens, employees, the youth, etc., are equally deserving of the respect that they are socially expected to show their government figures, bosses, elders, etc. If this is too much to ask of figures of authority, then perhaps, in the name of equality, we ought to be questioning, rather than blindly respecting authority. Anyone who demands your respect at the expense of your sense of self or basic human rights is clearly failing to treat you as an equal or as you deserve to be treated. In the wise words of Malcolm X,

“Be peaceful, be courteous, obey the law, respect everyone, but if someone puts his hand on you, send him to the cemetery.”