Former Irish quarterback John Huarte came out of seemingly nowhere in 1964 to win the Heisman Trophy. And had it not been for one phone call in the spring before his senior season, Huarte likely would have remained unknown.

In the spring of 1964, the Irish were scrimmaging inside Notre Dame Stadium. On one particular play, defensive end Harry Long cleanly drove Huarte — and his throwing shoulder — into the ground.

In pain and with some separation around his collarbone area, Huarte went to the hospital. The local doctors discussed surgery. They proposed putting pins around his shoulder.

First-year Irish head coach Ara Parseghian got on the phone with Huarte.

“Ara, they want to operate tomorrow,” Huarte recalled telling his head coach.

“Like hell they are,” Parseghian replied.

So Huarte waited a few weeks, began swimming and then started throwing lightly. In about six weeks, all the pain was gone, and he could throw fine.

“If they had to have surgery on me, you never would have heard of me,” Huarte said recently by phone. “That would have finished my career.”

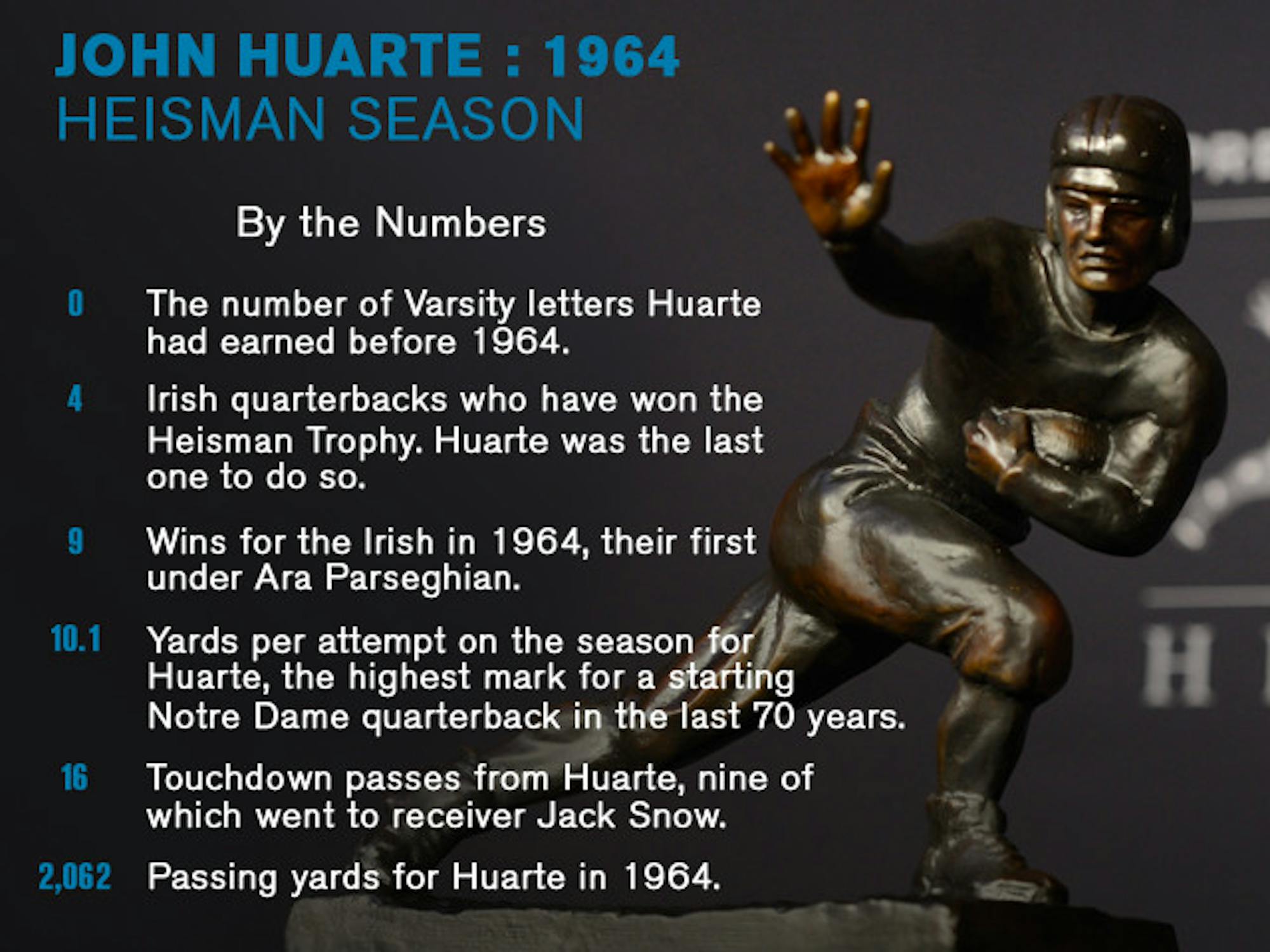

To that point, Huarte hadn’t had much of a career. He played sparingly in his sophomore and junior seasons. He hadn’t won a varsity letter.

But things changed when Parseghian left Northwestern for Notre Dame.

“Ara was just a top-notch coach and organizer,” Huarte said. “Ara had an intense voice, and when he spoke, he really commanded our listening. And if you didn’t [listen], you didn’t get too many chances.”

Huarte and the Irish capitalized on their chances in the 1964 season after stumbling to a 2-7 mark in 1963 — Notre Dame’s fifth consecutive season at .500 or below.

Huarte, despite not playing much, worked out with fellow California native and Irish receiver Jack Snow. They worked together in the summer, refining their skills.

“When Ara came along, we had the advantage of I kind of knew what Jack would do just by his body language,” Huarte said.

Huarte stayed focused on the little things — clean snaps, deceptive play fakes, proper dropbacks — in his preparation. And there wasn’t much time spent on anything but football and academics. Huarte didn’t have a car, and he didn’t have much extra money. He even once sold his summer-school food tickets to his roommate for $150 just so he had some spending money — even if it meant a six-week diet of peanut butter sandwiches.

A focused Huarte had a new opportunity when Parseghian took over the program. Parseghian and Huarte led the Irish to a 9-1 season that ended with a 20-17 loss to USC in the finale.

“What changed for me is just basically clear direction I got from Ara, what he wanted,” Huarte said of his personal turnaround.

Notre Dame scored at least 24 points in eight of its 10 games, and Huarte threw for 2,062 yards and 16 touchdowns en route to winning the Heisman Trophy. Huarte described Notre Dame’s offense as simple — typically an I-formation with Snow in the slot — but said Parseghian excelled as a play-caller. The head coach would hold a six-by-six card on the sideline and flash signals to Huarte just outside the huddle.

“All I had to do was execute,” Huarte said. “Ara was the field general.”

Huarte is the first to say he was not a skilled runner, but he proved otherwise in front of a national audience against Michigan State in mid-November at Notre Dame Stadium. On fourth-and-inches from the Spartans’ 23-yard line, Parseghian signaled for a quarterback keeper.

“I said, ‘Oh man,’” Huarte recalled with a hearty laugh. “The only way this is going to work is if you make a helluva fake.”

Huarte faked to his tailback, pulled the ball and scampered 23 yards around the corner and into the south end zone for a touchdown.

“So on national TV it looks like, ‘Man, he can run,’” Huarte chuckled. “Well, yeah, if no one tackles me, I can run.”

Huarte ran all the way to Heisman Trophy contention, putting him in the conversation with the likes of Tulsa’s Jerry Rhome, Illinois’ Dick Butkus, Snow and Wake Forest’s Brian Piccolo.

Then one day, Huarte was up on the second floor of Walsh Hall along with two of his roommates. The phone at the end of the hall rang, and one of Huarte’s roommates answered.

“John! John, you got it!” he yelled back to Huarte.

Huarte picked up the phone himself and heard Irish public relations man Dr. Charlie Callahan on the other end, delivering the news. Huarte called his parents, who would accompany him to New York. Huarte, who hadn’t even earned his first — and only — letter yet, had become Notre Dame’s sixth Heisman winner — the fourth and last Irish quarterback to win a Heisman.

One morning, 50 years removed from that unexpected season, Huarte, 71, sat looking out at the ocean in the Los Angeles area and reflected. He remembered getting his second- or third-grade report cards in Anaheim, California. There were his class grades, but also a grade for perseverance. Though his parents had to explain the meaning to him, perseverance stuck with him, Huarte said.

“Everyone has downs, disappointments,” Huarte said. “I think you have to sort of develop a habit of staying with things. In the long run, it really helps.”

Huarte admitted to feeling “pretty down” through his first three uneventful seasons at Notre Dame. At one point, he wanted to do some calculating. He added up all the hours he estimated he put into football at Notre Dame and divided that total from the value of his full scholarship. Huarte came to find out he was making roughly $23 per hour.

“I thought, ‘You shouldn’t really complain,’” Huarte said. “Just shut up and keep playing football.”

After his career in South Bend, Huarte played 10 seasons professionally — eight in the NFL and two in the World Football League. In 1977, after conversations with his brother Gregory and stints as a stock broker and real-estate broker, Huarte started the small Arizona Tile Company. Thirty-seven years, 25 branches, seven states and 650 employees later, Huarte’s family business is one of the major importers and distributors of granite, marble, Italian and Chinese tile on the West Coast.

Huarte’s two sons and son-in-law run the company for the most part. The former signal-caller spends his days visiting with his children and grandchildren, exercising, reading books on U.S.-Hispanic history and editorials in the Wall Street Journal.

Huarte, with his wife Eileen, recently made the trip back to South Bend in early September to be honored for the 50th anniversary of his Heisman Trophy. While in town, Huarte spent 30 minutes visiting with Parseghian. Naturally, the topic of Huarte’s from-out-of-nowhere, improbable Heisman run was part of the discussion.

Said Huarte: “Ara still says, ‘That will never happen again.'”