Three weeks ago, students crowded around TV screens, watching as votes trickled in from around the country.

Some cheered. Some cried. Across campus, emotions ran high as one of the most divisive election seasons in American history drew to a close.

Now, the country is starting to look forward and examine the implications of Donald Trump’s victory — and for University President Fr. John Jenkins, that means pondering what the election means for Notre Dame.

In an interview with The Observer on Thursday, Jenkins said he is considering inviting the President-elect to speak at this year’s Commencement ceremony.

“I do think the elected leader of the nation should be listened to. And it would be good to have that person on the campus — whoever they are, whatever their views,” he said. “At the same time, the 2009 Commencement was a bit of a political circus, and I think I’m conscious that that day is for graduates and their parents — and I don’t want to make the focus something else.”

Traditionally, the University has invited presidents to speak at graduation during their first year in White House. In 2009, President Barack Obama was the sixth president to deliver the Commencement address, following in the steps of Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush.

Jenkins said he plans to select a Commencement speaker sometime during the spring semester. Right now, he’s still weighing the different factors involved.

“My concern a little bit is that, should the new president come, it may be even more of a circus,” he said.

This election spurred levels political acrimony higher than Jenkins said he remembers in the past.

“I think it’s fair to say the election reveals deep divides in this nation — divides on political views, on economic prospects, educational differences, differences in opportunities,” he said. “And they run deep in the country.”

During this time, Jenkins said Notre Dame has a role as an educational institution to be a place of discussion that brings people together.

“I think being president of Notre Dame gives me a certain soapbox. You can say things that people will pay attention to what you say because of that. I take that seriously,” he said. “I try to use that soapbox that I have as well as I can to serve those ideas and not kind of advance a personal agenda.”

In a prayer service hosted six days after the election, Jenkins told undocumented students that the University would continue to support them, even if Trump were to rescind the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Program, as he promised to do during his campaign.

The DACA Program was the result of an executive order issued by Obama and allows some undocumented immigrants who came to the U.S. as children to gain work authorization and, in many cases, financial aid to attend universities. Last week, Jenkins signed a public statement in support of DACA, joining more than 400 other college and university presidents.

“These people were brought here as minors and are highly talented people, are valuable to this country,” Jenkins said. “So, if an administration would make changes, I would think trying to deport these talented young people would be among the most ill-advised moves they could make.”

“If there should be an effort to do that, we would do everything we can to fight that, whatever way we can,” he added. “Not only for these young people who are Notre Dame students, but for the good of the nation.”

In the past, the University has refused to give information on the immigration status of its students when asked by the state of Indiana. As a general policy, Notre Dame is guarded about giving any information about individual students to government agencies or other organizations, Jenkins said.

But it’s difficult to plan for the future at this point in time, he added, because no one can do more than speculate what policies the Trump administration will institute after the inauguration ceremony in January.

“I think it’s important at this stage to wait and to see and to listen,” he said.

Jenkins said, in the past, elections and other current events have created divisions within the campus political environment. But he called the demonstrations in the days following Trump’s victory the largest he’s seen during his time as University president.

“I think with the degree of animosity, the meanness of the rhetoric in the election, there was a lack of real discussion between the two opposing parties,” he said. “It does seem we have hit a peak or a sort of high point in terms of that animosity, that vitriol in public discussion.”

Jenkins said it’s the first time since the election of Abraham Lincoln that riots broke out in cities across the U.S. in reaction to a presidential election; now, America faces the challenge of finding ways to foster constructive conversations.

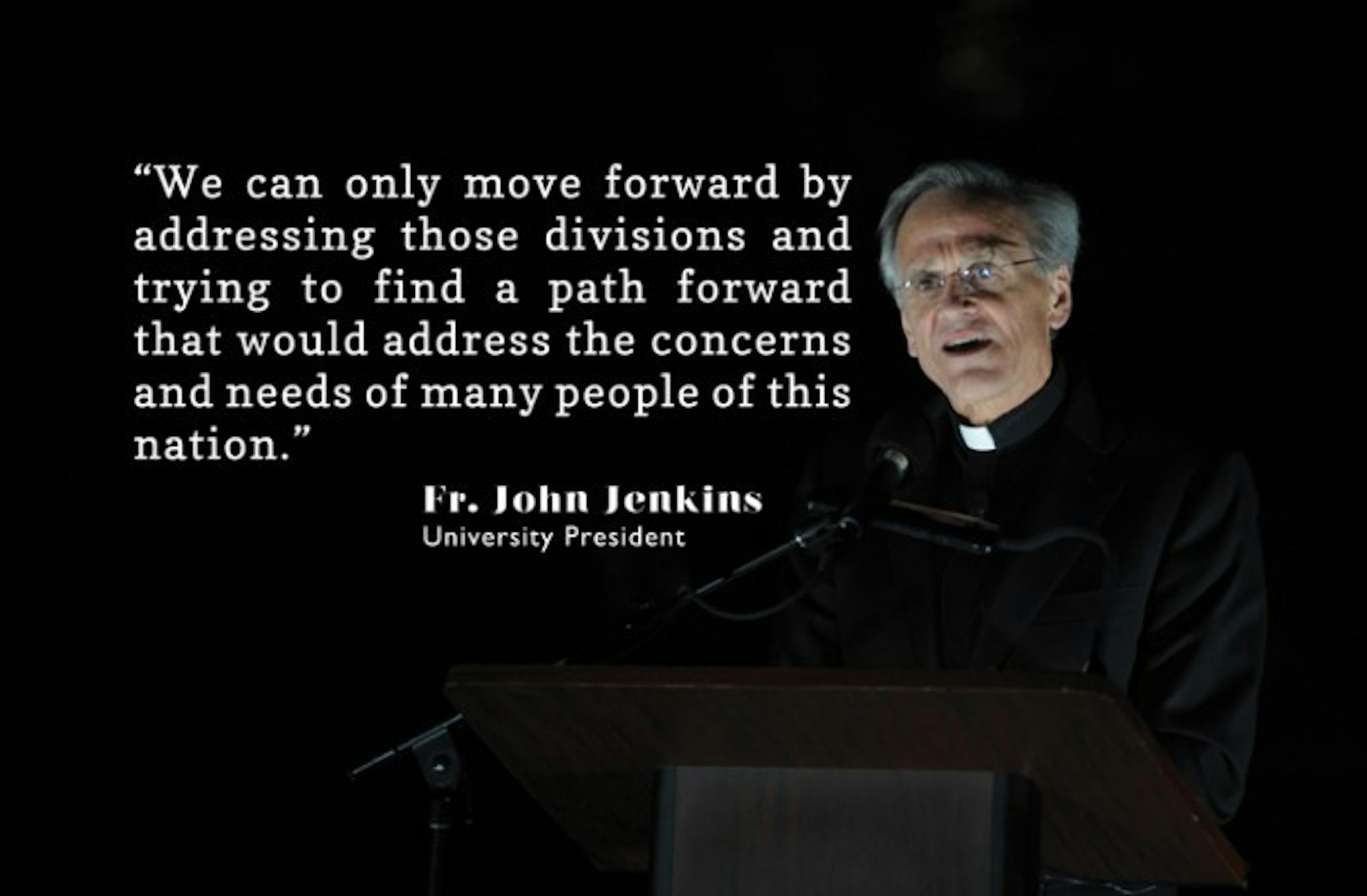

“The fact is we’re a democracy,” he said. “We can only move forward by addressing those divisions and trying to find a path forward that would address the concerns and needs of many people of this nation.”

Jenkins: No decision yet on Trump as Commencement speaker

Joseph Han, Chris Collins

Joseph Han, Chris Collins