BAZAAR, Kan. - It's no secret that Notre Dame is a place chock-full of mystique. As with many places that are tradition-laden, people stop asking "Why?" about certain questions and just accept it because it's the way it's always been. Don't walk up the front steps of the Main Building or you won't graduate. If you walk around the lake with a significant other, you better be ready to marry her. Don't tread on the God Quad grass, or else.

At what point do we lose our curiosity?

I've always been intrigued by KnuteRockne's place in Notre Dame lore. We know he went 105-12-5 and won three national championships, popularized the forward pass and put Notre Dame on the map, both in football and as a University. But what do we know about the man?

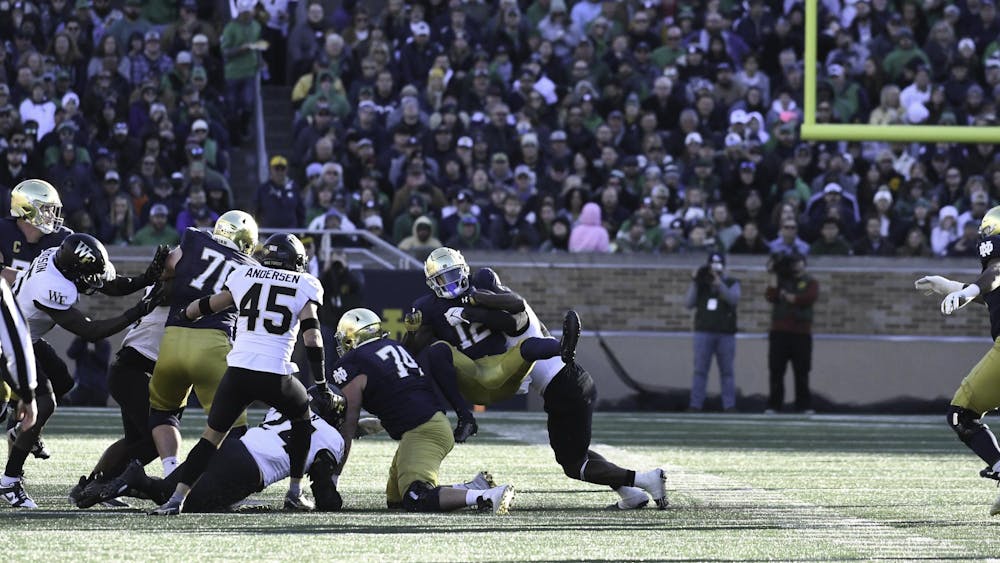

With Notre Dame's 12-0 season and impending national championship berth, I've grown increasingly inquisitive about who the man who got the ball rolling for the nation's most storied program. I, like so many others, didn't choose to attend Notre Dame because of football, but the sport is what put Notre Dame on the map. If it weren't for Rockne, how many of the 8,452 undergraduate students currently attending the University would actually be here?

I realized just how little I know about the man who started it all. Rockne is forever immortalized in bronze form outside the tunnel on the north side of Notre Dame Stadium. Realizing Irish coach Brian Kelly is one win away from getting his own statue someday, I considered what parallels, if any, exist between the two men.

It's unfathomable to think of a seemingly immortal Brian Kelly, but is that how he too will be viewed someday if he wins in Miami on Jan. 7? Will he be perceived as a man of destiny for Notre Dame, pulled by unseen forces to South Bend to fix the program after the failures of Davie, Willingham and Weis?

I've witnessed Brian Kelly in action the past three seasons. I've seen Brian Kelly struggle, fail and, in his third season, lead the Irish to within a game of adding a 12th national championship banner to the tunnel. I've seen Brian Kelly alienate the players recruited by the previous regime before ultimately endearing himself to them. I've seen him deal with tragedy and heartbreak. Through the highs and the lows, we've seen Brian Kelly the man.

I realized I needed to go find KnuteRockne the man.

***

I started at the end, the site of Rockne's grave at Highland Cemetery, a few miles west of campus. It's December in South Bend, and while snow had yet to hit the region, it is nonetheless a frigid day. The grass at the cemetery is not the luscious green you find during the summertime; it is transitioning to a season in which it will be covered by a snowy blanket.

Rockne's headstone is unremarkable in that it is no different from any other one at Highland Cemetery. It reads: "KNUTE K. ROCKNE," and lists him not as coach, but as "FATHER" above his name. Football is the source of his fame, but not of his identity. In the bottom left corner, his birth year, 1888, is engraved and the year of his death, 1931, in the bottom right corner. Some of the corners have been chipped off, probably by Notre Dame fans looking for a keepsake to cherish the myth.

But a headstone is hardly a glimpse into a man's life. Needing to quench my desire for more information on who this man was, I headed to Notre Dame Archives on the sixth floor of Hesburgh Library. I discovered Rockne wrote guest columns for different publications, including Notre Dame's own Scholastic Magazine. The topics ranged from the virtue of collegiate athletics to football strategy.

In one of his accounts, when recalling his initial reaction to a friend's suggestion that he play football at Notre Dame, Rockne said, "Who ever heard of Notre Dame? They've never won a football game in their lives."

But of course he ultimately decided to attend Notre Dame and, looking through the archives, I can't imagine what the University in 2012 would look like had he chosen another path.

When perusing through items related to the airplane crash in which Rockne died, the most striking visual was a photograph of Rockne's rosary. The black rosary snapped in two places on impact and the bottom of the miniature crucifix is bent. When authorities arrived at the scene of the plane crash, they found him clutching it in his hand.

What was swirling through Rockne's mind as the plane plunged to the frozen earth below? Notre Dame? His family? His mortality? A prayer?

***

Rockne boarded the F10 plane in Kansas City at 9:15 a.m. on March 31, 1931. It was an icy day, and the pilot lost control of the plane when ice froze over the left wing in Bazaar, Kan., 140 miles southwest of Kansas City.

Fourteen-year-old Easter Heathman heard the plane above but could not find it in the cloudy sky. He heard the wooden plane carrying eight people tumble into the hillside. Each one died instantly.

Later in the 1930s, a memorial was constructed at the site in to honor Rockne and the seven others who perished at the scene. Heathman maintained the grounds from then through his 2008 death. The University honored him in 2006 for his service with an honorary monogram.

Rockne and his team always returned to a boisterous crowd of thousands at Union Station in South Bend after prevailing in an important road game. The final time he arrived at Union Station, it was in a casket. Nonetheless, thousands gathered. This time, it wasn't in support of KnuteRockne the coach. It was in support of KnuteRockne the man and the wife and children he predeceased.

In order to fully find Rockne, I needed to drive Bazaar, Kan., and see and feel the memorial for myself. How could I expect to truly understand the man unless I traveled into his past to the location of his untimely death?

***

Observer colleague Kevin Noonan and I drove more than 1,700 miles in three days across the Midwest and into the Great Plains to find KnuteRockne. Easter's son, Tom, now leads occasional tours to the site. ("My dad always said, 'I've taken a lot of people up here, and not one of them was a dud.'")

It's Saturday afternoon, and we park at a one-room schoolhouse in Bazaar to meet him.

He arrives in a black pickup truck and tells us we should all ride together, "because the rental car won't make it on this terrain."

We hop in the truck and Tom drives toward the site. Kansas is experiencing a pretty rough drought, so the ground is dry and the grass yellow. In order to reach the memorial, he opens two gates that are locked with a combination to keep horses and cattle inside.

We trek through the bumpy trail, and after a few minutes we can see the memorial atop the hill.

Upon sight, we are speechless. Nothing but plains stretch beyond the memorial for miles. Engraved on the granite monument are eight names. Atop the list it reads, "ROCKNE MEMORIAL." There is a small wiry fence around the monument Easter constructed years ago to protect it from the cattle.

Even today you'll find bits of glass from the plane sitting atop the soil. It was a cloudy day when we were there, but Tom said when the sun shines or the rain pours down, you can see the hill shine from miles away.

Perched atop the hill, the world comes to a halt. I picked up a couple small shards of glass, and was immediately humbled as I realized I was handling one of the last remaining physical connections to KnuteRockne, the man.

Suddenly, it all makes sense. Rockne needed to die a heroic death for the myth to be this grand and everlasting.

While his name is the only one remembered of the eight who died in the crash, in that moment he was just as vulnerable and helpless as the others aboard the flight. When it dove into the hill in the middle of America with nothing around them, KnuteRockne the man ceased to exist, but the legend found a new beginning.

***

On the trip back to South Bend, we stop near Kansas City to meet Kay Sizelove. Her father, Paul Kennedy, ran track for Rockne during the early 1920s. He was the team captain and an accomplished mile runner.

On one occasion, when the team was aboard a train to South Bend after a meet, Rockne pulled Kennedy aside. He asked Kennedy to join him in a different compartment. Kennedy was worried he had done something wrong and wondered why the coach singled him out.

When they reached the adjacent room, they sat down and Rockne looked into Kennedy's eyes.

"I need your help, Paul," he said. "My wife and my anniversary is coming up soon. I don't know what to get her.

"What should I get her, Paul?"

Even when Rockne was in his element, among his athletic squads, he could not help but think of his wife.

***

After meeting with Kay, we took an indirect route back to South Bend and met Sr. Anthony Wargel, a 98-year-old Ursuline nun, in Louisville. A lifelong Notre Dame fan (she paces with her walker while watching the Irish play), she remembers the national impact of Rockne's death when she was a 17-year-old girl growing up in Evansville, Ind.

As a woman who has devoted her life to religion, Wargel considers Rockne's faith to have been his most striking characteristic.

"He was so inspired that the boys would always make it to Sunday Mass, regardless of when or where they played, that he converted to Catholicism," Wargel said. "That tells you about a place like Notre Dame."

Rockne converted to Catholicism in 1925 (in fact, he was baptized on campus in St. Edward's Hall), and just six years later, as a 43-year-old man, he died clutching a rosary.

He wasn't just a football coach. He was a God-fearing man who worried about what to get his wife for their anniversary and where to spend time with his children.

That's KnuteRockne the man. As the days pass by, that image fades from our consciousness and the mythic figure builds. Even his grandchildren don't know who KnuteRockne the man was. Pretty soon all we will have are legends and tales.

***

When I return to South Bend, I call Knute's grandson, Nils Rockne, who resides in San Antonio. His father, Jack, was 5 years old when Knute was killed in the plane crash, so even he had limited memories of his father to share with Nils.

As I explain to Nils my search for his grandfather, he interrupts me.

"Excuse me, but I have to correct you. You're saying my grandfather's name wrong. It's 'Kuh-newt'Rockne, not 'Newt' Rockne."

It says a lot about how his myth has perpetuated that we don't even pronounce Rockne's name correctly.

The only vivid memory Jack passed down to Nils was playing on a Miami beach in March of 1931: Knute the father enjoying a respite from football season with Bonnie and their sons, oblivious to the impending tragedy that would shake a family and a university and consume the nation.

There, in Miami, KnuteRockne the man existed for what would only be a few more days. The man would soon be replaced by myth and legend in an obscure Kansas field.

There, in Miami, Brian Kelly will descend on Jan. 7 to try and secure his position among Notre Dame immortals with Rockne, Leahy, Parseghan, Devine and Holtz.

There, in Miami, the birth of the Brian Kelly myth can take place. If he wins, his story will span generations to come. If he wins, when the man is gone, only the myth will remain.

Contact Andrew Owens at aowens2@nd.edu

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Observer.

Sports writer Kevin Noonan contributed to this report.