Editor’s note: This is the first installment in a two-part series discussing two South Bend families’ experiences with the 1994 Rwandan genocide, in light of Notre Dame’s commemoration of the 20th anniversary of this tragedy to take place April 26.

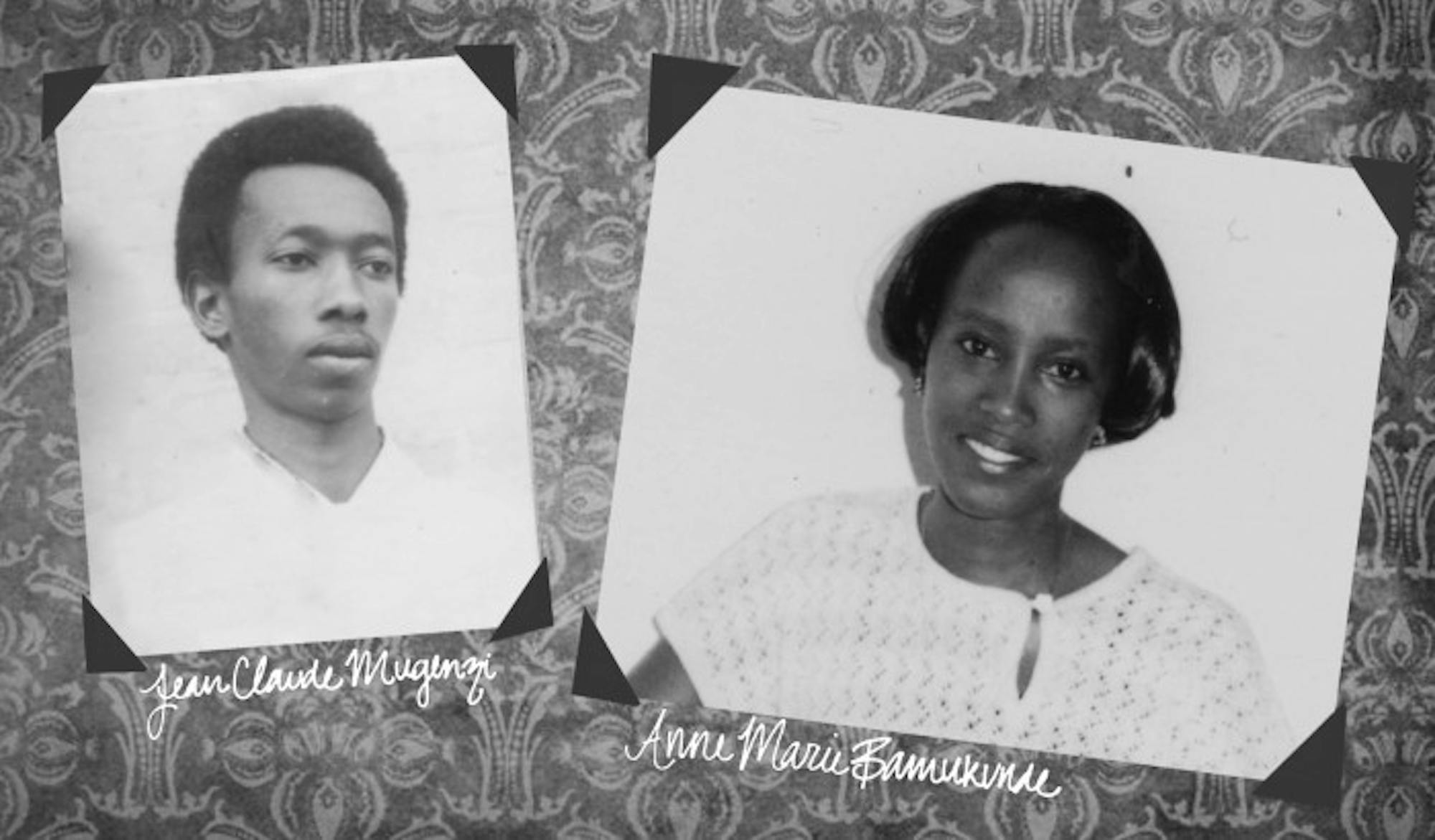

Jean Claude Mugenzi cannot lie face down in his bed without thinking of his father and siblings’ murders and his own bullet wound.

Mugenzi and his wife Anne Marie Bamukunde, now South Bend residents, survived the 1994 Rwandan genocide against the Tutsis, in which one million people were killed in 100 days.

Mugenzi, who was 24 at the time of the genocide, said he fled with his parents and four siblings for 80 days from the killers.

“There was nowhere to run because the neighbors knew where we were,” he said.

“They were home. So we fled. We saw some of them coming, and we managed to flee through banana trees, and we spent several nights in a swamp near where we come from.

“We could hear them looting our property. We could hear them. We could hear the cows screaming because they were being taken away. Even though they are animals, they can feel. They know there are intruders in the home.

“We could hear them removing iron sheets from our house, so there was a lot of noise and commotion. You feel uprooted right then and there. You’re sitting, hiding in the middle of a swamp, wondering if you’re going to make it on the other side, how you can hide maybe at a friend’s house before the killers discover you. And you hear all of that. You just realize, ‘This is the end.’”

Mugenzi and his family sought refuge with Hutu friends throughout the country but could not stay long in one location, he said.

“We would be discovered sometimes and get tortured and get stripped,” he said. “We had to walk almost naked and bare-footed. … Thanks to an old Hutu friend, we would escape sometimes when [the killers] stopped us at the roadblock when they were about to kill us.

“I remember one time there was a Hutu who used to farm our fields who told the others, ‘I will take care of them,’ meaning, ‘I will kill them.’ He took us to a different place where we spent several days, and of course, after that time, we had to be on the move again.”

Mugenzi said he and his family were “caught by surprise” one night when they had tried to reach a camp operated by Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) rebels.

“There was a group of people with knives and guns,” he said. “They ordered us to lay face down, and they started killing. Before they got to me and some others, the rebels arrived and shot from a distance.

“When they heard the shots, the leaders said, ‘Shoot them all.’ So they started shooting, so I got shot, and my father and the others didn’t make it. Only my mom managed to slip away through the bushes and my two little sisters.

“So I was left for dead in the cold blood, and I could see left to right, one was dead. I could see my younger brother agonizing, and there was nothing I could do to help him. So then there was fighting for what seemed to be an eternity for me, but after that, the RPF rebels took me with their injured to a make-shift hospital, where they treated me for the next maybe two weeks before I was reunited with my mom and my two sisters because they went a different way. They didn’t know that I survived.”

Bamukunde said she also lost most of her close relatives in the genocide.

“Sometimes I don’t trust people because of what happened,” she said. “I was 16 at the time of the genocide, so I lost my dad. I lost my brother and many aunts and uncles and many friends of our family.

“So it was like after genocide, we were just alone, and we were just trying to organize ourselves. It was a new life to many people.”

Mugenzi said one way survivors have tried to honor the memories of their loved ones is through ceremonial burial.

“When they were killed, they were just thrown wherever,” he said. “Some were lucky to bury them a few days later, but in make-shift tombs. Others were lost completely. We don’t know where [my wife’s] dad was. We never found him and her brother. And it’s the case for many survivors.

“So when you’re lucky to know where your loved ones were left, to bring some closure, you bury them with respect and dignity at a memorial site, a genocide memorial site. We did that for my older brother who was killed in Kigali.”

To help other survivors process their experiences during the genocide, Bamukunde said she became a psychiatric nurse in Rwanda.

“The concept of mental health was new,” she said. “Psychiatric nursing was new in our country before genocide. So they told us about mental health and they told us it’s about counseling.

“It’s about taking care of people who have been through psychological programs, trauma, genocide. … I had some friends who went to [nursing] school together who were all genocide survivors, and we were all interested in doing that because we were thinking we could also reach out and help our family, friends and many other survivors.”

Bamukunde said she treated many patients for trauma as a result of the genocide, even people who were in their mothers’ wombs during that time. Therapy has helped these and many other survivors to understand their feelings, she said.

“We were trying to really listen to them and trying to go through all those stories because sometimes I felt like the story was too much for them, too hard,” she said. “So talking also helps them or using cognitive therapy, talking about the thoughts that they have that doesn’t help them, trying to change them [or] trying body relaxation.”

To educate others on genocide, Mugenzi makes documentary films, he said. Mugenzi said he and Bamukunde moved to the United States five years ago so he could attend film school at Columbia College Chicago, from which he will graduate in May.

“[My wife] always says, ‘Why didn’t you go to law school or something else in the country?’” he said. “I said, ‘I don’t understand. That is something I don’t want. I will find what I want, whatever it is, and I’ll go for it.’ So I came here to pursue that dream of mine, and thank God I’ve almost reached it, almost.”

Mugenzi said he and Bamukunde moved to South Bend a year ago because of their love of Notre Dame and the strong Rwandan community here.

“The first time I came to the U.S., I think we came to the Basilica [of the Sacred Heart],” he said. “I’m Roman Catholic, so with friends we came to pray here. We would come almost every Sunday. I love this Basilica. I love this place. … Maybe my kids will come here to study, or maybe I will get a job here.”

As both Notre Dame and the world remember the 20th anniversary of the 1994 Rwandan genocide, which took place from April 7 to mid-July, Mugenzi said the genocide is “always present” to survivors, no matter the year.

“I should tell you that it took me probably 10 years before I could look at the moonlight and enjoy it, because whenever the moon was out we couldn’t come [out] from hiding and cross a road or something to go into another hiding,” he said. “So I hate it for that. … And it’s a little thing, to not be able to enjoy nature because of what I endured during the genocide, or not being able to lie down lazily in my bed [face down] because that’s how my people got killed. That’s how I got shot, in this position.

“Our life is disturbed by many little things. There are things you can’t take for granted that some people do. Some people are not even able to enjoy life because of their history.”