Several Notre Dame students have come together to produce a magazine as part of a social awareness campaign combatting the fast fashion trend of buying and throwing away clothing items made in sweatshops. The magazine will promote slow fashion, fair trade, made-in-America brands and thrift store shopping.

According to Marie Bourgeois, a research associate with the visual communications design (VCD) program, the social awareness campaign is a larger project under which students create their own campaigns based on societal issues they see.

“The Visual Communication Design 8: Design for Social Good class was started by professor Robert Sedlack, who brought a model of social design to Notre Dame's VCD program,” Bourgeois said in an email. “Throughout his seventeen years teaching at Notre Dame, he would have students create social awareness campaigns focusing on contemporary issues in society. I have been a guest critic on these projects for years throughout my graduate school career at Notre Dame, and after graduation.

"Last fall, I had the joy of being able to co-teach with Robert for the Design for Social Good course, which brought me closer than ever to the brilliant projects he had conceived and perfected. Robert and I agreed last spring, before his passing, that we would teach this class together again this fall, so I have decided to keep as true to his structure for the course as possible with this semester's class.”

“Typically, students gear their campaign toward the University community,” Bourgeois said, “Such campaigns have received a great deal of attention from Notre Dame students, faculty and staff over the years, as our design students tend to come up with creative, striking interventions that disrupt daily life on campus and cause viewers to think deeper on an issue that may not be top-of-mind.”

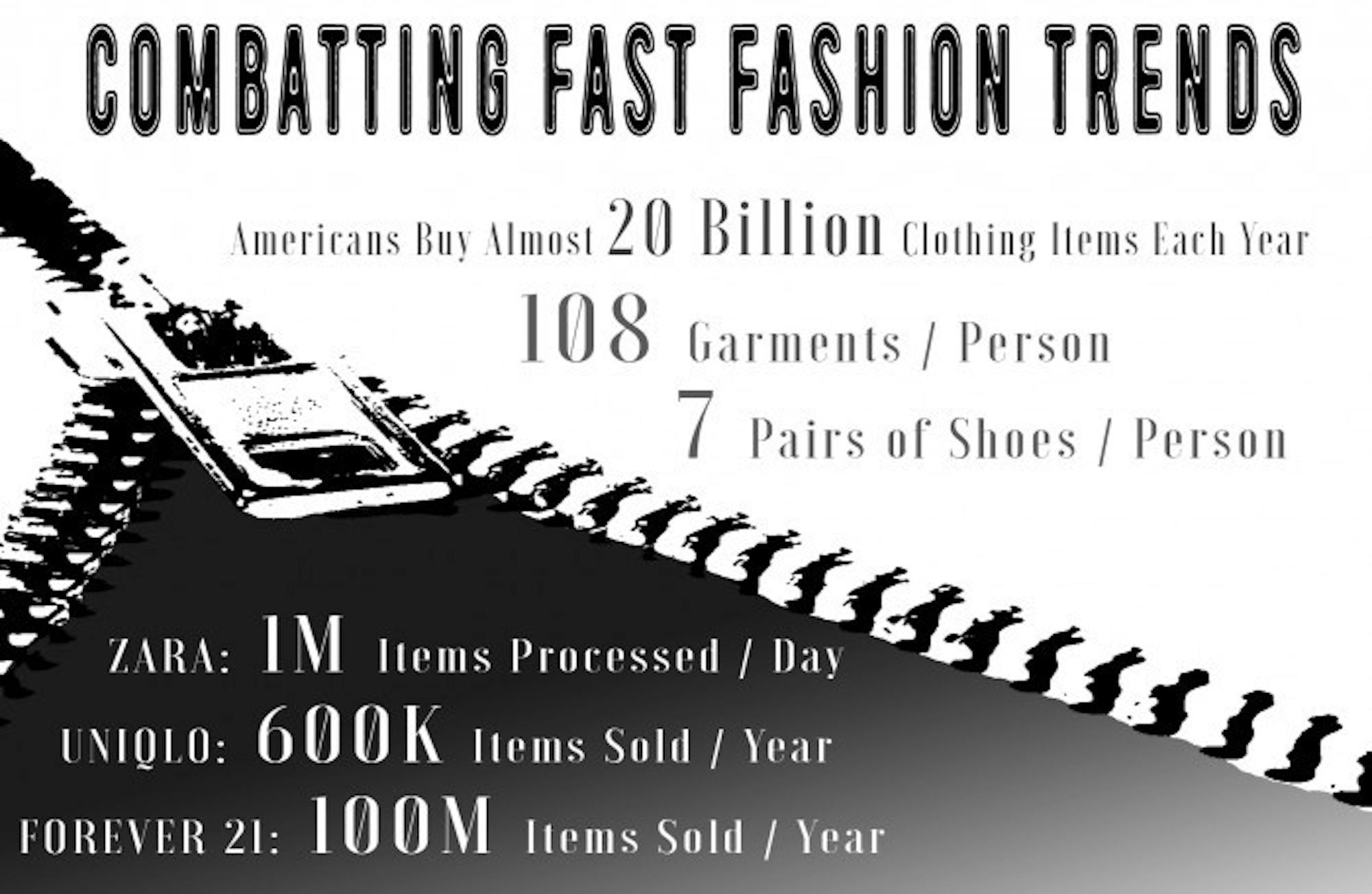

Juniors Amy Ackermann and Mary Kate Healey have combined forces to create a magazine to combat ‘fast fashion,' a trend that, according to Bourgeois, has been steadily rising over the past two decades (Editors Note: Ackermann is a photographer for The Observer). Fast fashion is “the shift within the fashion industry toward cheaper, more rapid production of items," she said.

Many of the most popular clothing companies among young adults have participated in fast fashion behavior in order to be able to offer high-fashion products at slashed prices through quick turn-around.

“One major outcome of this market trend toward fast fashion is that a style's season is greatly shortened — what used to be six months or longer is now measured in weeks,” Bourgeois said, “This is results in huge profits for companies as they are able to sell at higher volumes, encouraging consumers to buy cheaper clothing more frequently, contributing to a sense that clothing is somewhat disposable."

Bourgeois said the fast fashion model exploits vulnerable populations in an effort to drive down the cost of goods and contributes to environmental concerns.

"When clothing is viewed as disposable, that is exactly what happens to it. Many of these cheap garments are ending up in landfills where their synthetic fibers are releasing toxins into the atmosphere," she said. "Every step of a garment's production, from dying to sewing, to packaging, can create harmful pollutants if the environment is not a top focus throughout the making process. The cheaper the production, the less the environment is considered.”

According to Bourgeois, as found in Elizabeth L. Cline’s book “Overdressed: The Shockingly High Cost of Cheap Fashion," between 1996 and 2011, more than 500,000 American garment industry jobs were lost due to apparel production being outsourced to outside of the United States. Finally, only 20 percent of donated clothes are sold in charity thrift shops. Around 50 percent is turned into fibers or wiping rags, and the rest is shipped overseas and used as clothing

“In high school, I spent a week helping out at a thrift store in northern Minnesota,” sophomore Emily Schoenbauer said, “What I learned there was shocking. In the back room, there was a mountain of clothing ...

"I realized that all of those racks of clothing in department stores that I usually sifted though mindlessly were going to end up in someone's closet, be worn a dozen times, go out of style, and then be brought where? Places like this where they have more than they know what to do with? In the garbage? No matter where it ended up, I now know that there is an unsustainable amount being produced. Something has to be done.”

Schoenbauer is serving as a model for the project.

“It simply involves having a super fun photo shoot with Amy [Ackermann] while wearing some of my favorite clothing items that I have bought sustainably, like a dress from a thrift store, a sweater from a garage sale, and even a couple blouses that I may or may not have permanently borrowed from my mom,” Schoenbauer said.

Ackermann and Healey have prepared for the magazine’s production by researching fast fashion statistics and information, interviewing fellow students about their buying habits and collecting stories about ethically produced clothing items.

“Their hope for the project is to encourage our generation to start buying clothing more sustainably,” Schoenbauer said, “The way the fashion world works right now requires that people who want to stay up-to-date should be buying basically a new wardrobe every couple years. Think about the racks upon racks of clothing that are in every Forever 21 or H&M around the country. That is not all being purchased, but they will overproduce their cheap merchandise to ensure that they make as much profit as possible.

"We have created a never-ending cycle of waste through something that seems harmless, wanting to look your best. That is why … we have to begin shifting our mentality. While it is fun to buy the low quality, merely-for-dollars shirt from the department store, we can find even cheaper, more unique options at second-hand stores, which are everywhere.”

Schoenbauer said students should know that the magazine is not calling for radical lifestyle changes.

“I still shop at the mall ... I would just like to ask people to start making small changes," she said. "Next time you're going shopping just for fun, decide to peruse through Goodwill. If there are local garage sales happening, stop by. I guarantee that you will find something cheap and incredibly special to you.”

Bourgeois said these campaigns serve to promote deeper thinking on issues surrounding our everyday life.

“With this particular campaign, the hope is that my students will bring more meaning and understanding to something so ubiquitous as clothing," she said. "The reality of that garment, however, goes back to the crop that was harvested to create the fibers for the material. ... With heightened awareness around something we as consumers encounter daily, we can begin to make choices that push the industry toward a more desirable and thoughtful means of production."