This is a response to Mimi Teixeira’s article “Is Income Inequality Really that Bad?” published two weeks ago. This is the second installment of BridgeND’s Income Inequality series. All responses, arguments and constructive criticisms are welcome.

“The issue of wealth and income inequality is the great moral issue of our time, it is the great economic issue of our time and it is the great political issue of our time.” – Senator Bernie Sanders

I suppose quoting Bernie is one way to share your political views bluntly. However, that is not my intent. I agree with the Senator on some things, especially his core premise that income inequality matters. However, the political crusade he and others lead to rectify persistent inequality often misses the point. Unequal wealth distribution is not in and of itself an injustice, at least not in our constitutional system. If we redistribute the wealth, what really have we gained other than forced and unnatural equity? So, many people would prefer instead to focus on opportunity inequality. But this too does not do the issue justice. Income inequality is not simply a symptom of opportunity inequality, but a fundamental cause of it. However, this does not take away from the fact that the issue of income inequality in itself is a misnomer. The buzzwords “income inequality” narrows and minimizes the problem of structural inequality to a mere question of money. If the phrase income inequality is to be anything more than empty rhetoric, we need to start focusing on the substance of the issue — it’s creation, it’s causes and credible solutions.The unequal distribution of wealth in our nation is a small part of a much larger structural problem which unequally favors a few while systematically disadvantaging many. While Teixeira argues income inequality is a natural byproduct of capitalism, I argue the opposite. While a degree of inequality is normal and even beneficial, the fact of the matter is that the level and nature of inequality in America is not natural, but is created. I argue that this systemic inequality is built on three foundations: the failings of federalism, past and present institutional racism and convoluted and inherently unequal fiscal policies. All of these factors do more than cause or allow inequality; they are a fundamental affront to the values of liberty and self-determination enshrined in our founding documents. That is why income inequality and all structural inequalities are the defining political and economic issues of our time.

The failings of our (admittedly genius; thanks Hamilton!) federalist system play a crucial and too often unnoticed role in perpetuating inequality. The negative effects are most evident in infrastructure and education — both funded almost entirely by local tax bases.

Our infrastructure is nationally rated as a D+. Like many national issues, this lack of infrastructure unequally affects the poor. Cities like Flint, Michigan lack the resources to replace lead pipes or remedy the situation which officials caused (mostly due to shortsighted fiscal policy). The burden of infrastructure repair and investment is placed almost entirely on local governments, which means poorer areas have tremendous difficulty securing funding for improvements. Despite the fact that clean water and transportation are universally considered fundamental rights, our federal system does not leave much room for a remedy. People do not like to pay for other people’s stuff — and hence there is constant pushback to any effort to regulate or fund local infrastructure programs from the state or national level.

A similar problem exists in American education. Gross disparities exist in funding and have not met with any widespread remedy. This system of unequal funding means that poorer children — who typically have no choice in the schools they attend — almost certainly receive a lower quality education than those students in middle class and upper class districts. There has been immense pushback, typically enforced by the courts, to most efforts to distribute education funding equitably. The idea of revenue sharing has been enacted in some states whereby all districts receive funding based on the same formula, not contingent on their tax base. But most states have chosen to dodge the divisive issue of school funding by leaving current, inequitable systems intact.

Since our federalist system fails in these regards, lawmakers must act to guarantee certain rights such as education and infrastructure for all Americans. Until we do this, the gulf between rich and poor will only expand and millions will continue to be denied their fundamental right to self-determination.

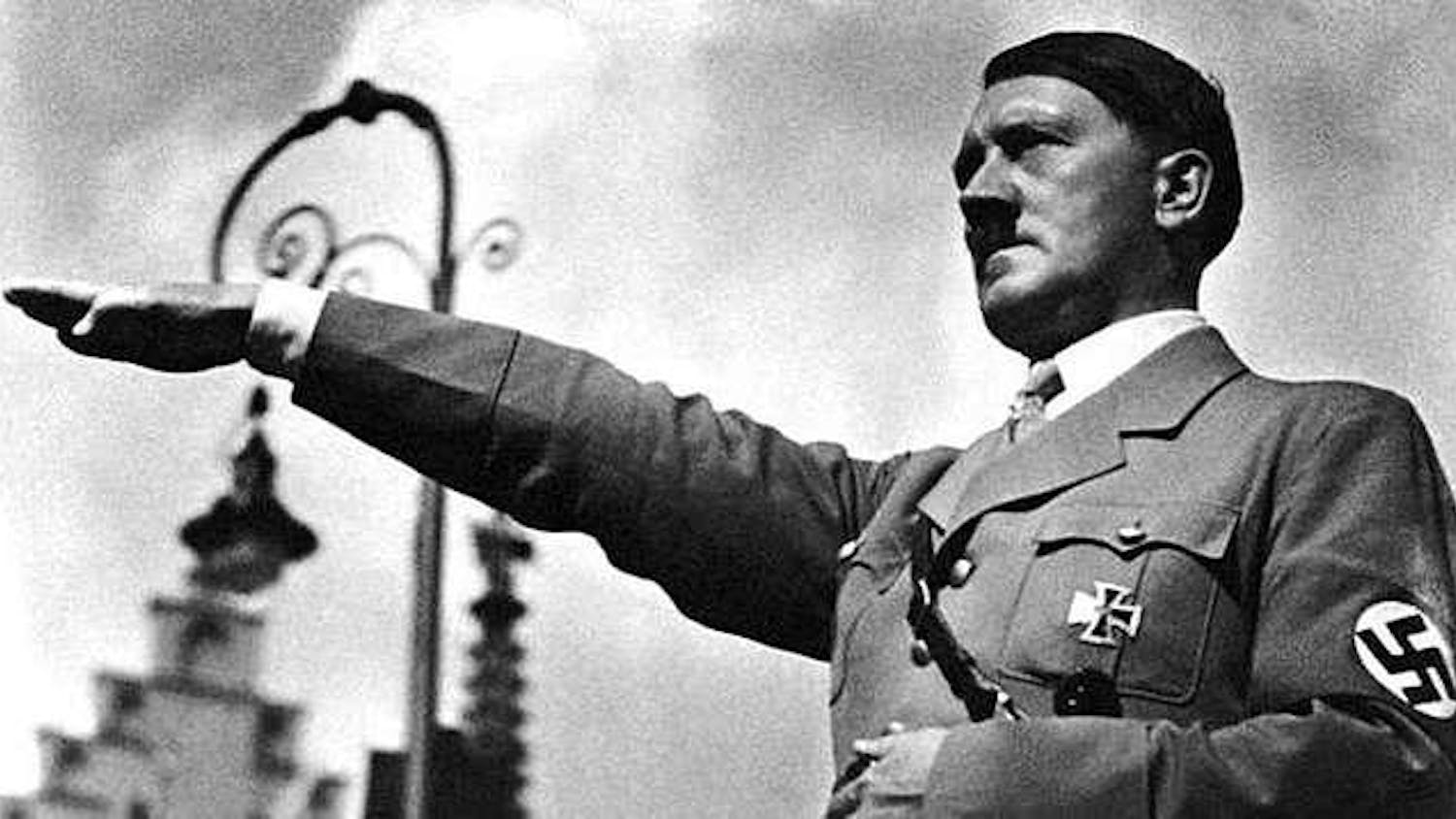

Many would prefer to ignore the role of race as a cause that perpetuates economic inequality. This unwillingness to address racial issues will stymie and hamper any efforts to address the problem of income inequality. Poverty rates among people of color are more than two and a half times as high as among whites. Unless you want to adopt a doctrine of racial inferiority, then it is necessary to address why certain populations are endemically disadvantaged.

However the remedies for this problem thus far — the Reconstruction amendments, Brown v. Board, Civil Rights legislation and Affirmative Action programs — have never addressed the roots of injustice. The blatantly unjust law is patched and amended; our government and our people effectively say “oops!” and move on, patting themselves on the back for being champions of equality and democracy. I do not advocate for a blame game or to shame your sense of patriotism. But instead of apologizing and blaming we should seek to make right what we had in the past done wrong — but we have not and do not.

After Reconstruction was abandoned, two main issues have had a particularly poignant and lasting effect today: schooling and housing.

While many point to Brown v. Board as the end of racial inequality in America, this is not the case. While progress began to be made by the 1970’s, in many ways America’s schools are just as segregated and unequal as they were before the Civil Rights Acts. Local funding ensures inequality is reinforced in low income districts. Even more troubling, several studies have shown majority minority schools are funded significantly less than their majority white counterparts of the same socioeconomic composition. While affirmative action has decidedly increased the diversity of American colleges, these efforts have been severely challenged ever since the late 70s; quotas were deemed unconstitutional in Regents v. Bakke, effectively denying minority students recourse for more than a century of intense exclusion. Affirmative Action programs that consider the whole person — particularly one’s race and socioeconomic class — are a necessary and essential remedy for the inequality of our system.

Black Americans were also essentially deprived of affordable housing and healthy neighborhoods. Many cities in the North, and until 1968 the federal government, sanctioned a racial practice called redlining where banks would cordon off entire areas of cities where residents of color lived, marking them unfit for investment. This practice denied millions of minority families’ access to a reasonable mortgage and inspired disinvestment in minority communities; worse yet, even after the 1968 housing act, the practice continues in many ways. Hence neighborhoods many excuse as products of "de facto" segregation were actually deliberately segregated, and remain so. Businesses fled or closed as disposable incomes dwindled due to unfair leasing agreements. Middle class families left if they could afford the loss on the sale of their home. Schools lost adequate funding and qualified teachers. City governments and developers no longer invested in hospitals, cultural attractions or parks in these "bad neighborhoods" and hence inequality became cyclical.

Lastly, fiscal policies that create and sustain inequality must be rooted out and rewritten. The tax code is generally so convoluted only the relatively well-off can navigate it and exploit the ample loopholes available. Large corporations often end up paying far less than they should. The infamous Citizens United case only makes income inequality more drastic, as money now has a direct and unfair role in the political realm. Loopholes need to be closed, corporations and the rich need to follow fair tax laws and lawmakers need to stand up to their own special interest and fix the broken and inequitable campaign finance system.

As Americans, we need to realize these structures of inequality exist and we have a civic duty to encourage our lawmakers to address them. I do not advocate for wealth redistribution. I am not anti-business. I do not pretend welfare as it is merely needs to be expanded in order to solve all of our problems. But if we strive so determinedly for a culture of individualism, merit and self-determination, then we should at least be committed to making the rules of the game fair.

Inequalities that are determined by anything other than skills, contribution or hard work need to be addressed and counteracted. It is not normal, it is not neutral, it is not natural. By claiming the glaring inequalities in our society — racial, structural, economic — are simply part of life, people willfully ignore reality. But when we throw around the terms income and opportunity equality for political expediency we avoid having a substantive debate on the true causes of this issues and how we can come together to fix them. The current level of income inequality in the U.S. is not a natural byproduct of capitalism. Our nation has gradually constructed and continuously reinforced structures of inequality. It is time to face the facts and work to dismantle these artificial bulwarks that favor some at the expense of many. We created a monster, now it is our turn to tame it.

Adam Moeller is a history and economics major with a minor in education, schooling and society. He lives in Sorrin College and can be contacted at amoeller@nd.edu