Writer’s Note: This analysis discusses specific plot points from “Boogie Nights.” I want everyone’s first viewing of “Boogie Nights” to be as magical as mine, so please refrain from reading further if you’ve not yet seen the movie.

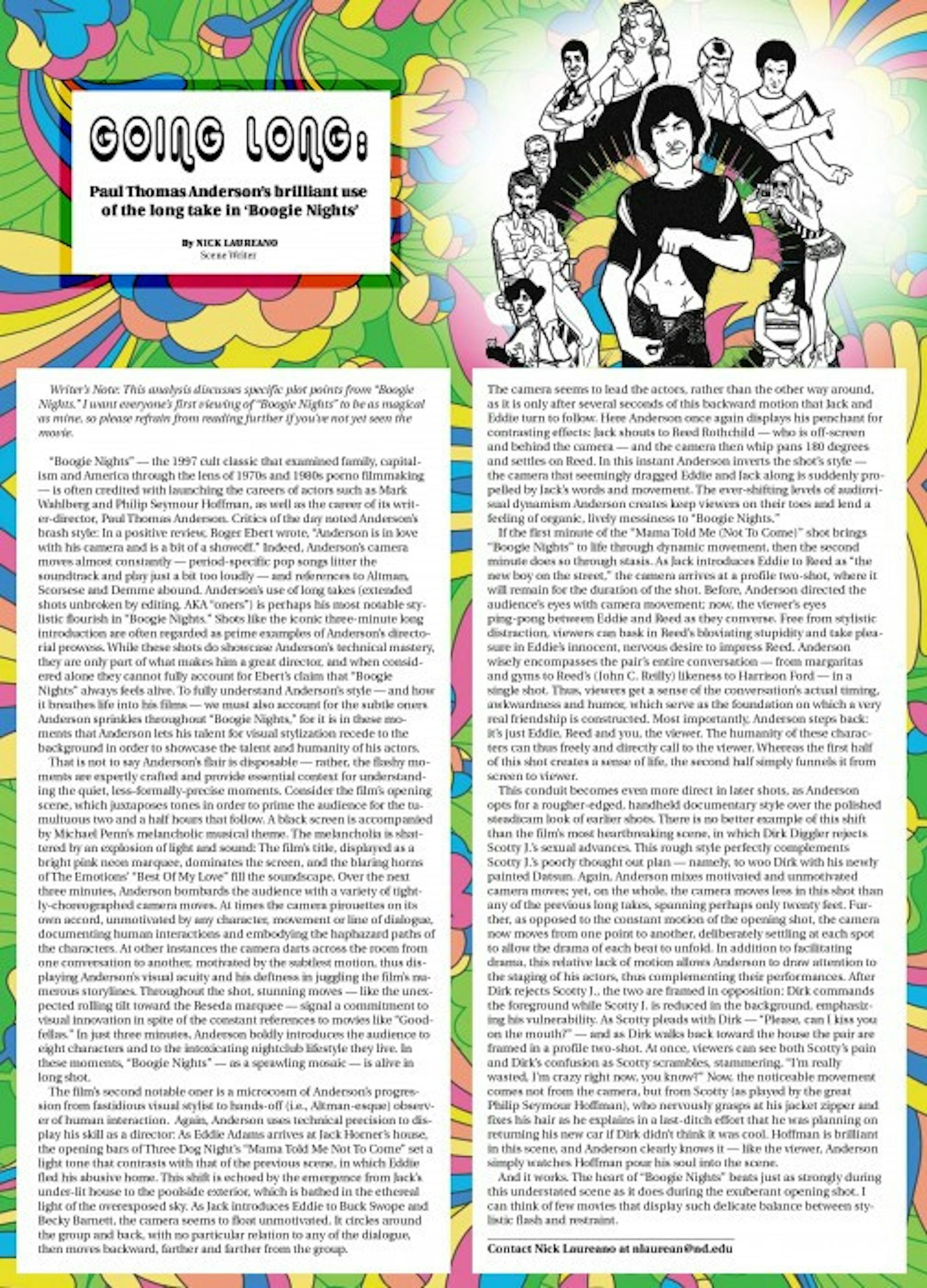

“Boogie Nights” — the 1997 cult classic that examined family, capitalism and America through the lens of 1970s and 1980s porno filmmaking — is often credited with launching the careers of actors such as Mark Wahlberg and Philip Seymour Hoffman, as well as the career of its writer-director, Paul Thomas Anderson. Critics of the day noted Anderson’s brash style: In a positive review, Roger Ebert wrote, “Anderson is in love with his camera and is a bit of a showoff.” Indeed, Anderson’s camera moves almost constantly — period-specific pop songs litter the soundtrack and play just a bit too loudly — and references to Altman, Scorsese and Demme abound. Anderson’s use of long takes (extended shots unbroken by editing, AKA “oners”) is perhaps his most notable stylistic flourish in “Boogie Nights.” Shots like the iconic three-minute long introduction are often regarded as prime examples of Anderson’s directorial prowess. While these shots do showcase Anderson’s technical mastery, they are only part of what makes him a great director, and when considered alone they cannot fully account for Ebert’s claim that “Boogie Nights” always feels alive. To fully understand Anderson’s style — and how it breathes life into his films — we must also account for the subtle oners Anderson sprinkles throughout “Boogie Nights,” for it is in these moments that Anderson lets his talent for visual stylization recede to the background in order to showcase the talent and humanity of his actors.

That is not to say Anderson’s flair is disposable — rather, the flashy moments are expertly crafted and provide essential context for understanding the quiet, less-formally-precise moments. Consider the film’s opening scene, which juxtaposes tones in order to prime the audience for the tumultuous two and a half hours that follow. A black screen is accompanied by Michael Penn’s melancholic musical theme. The melancholia is shattered by an explosion of light and sound: The film’s title, displayed as a bright pink neon marquee, dominates the screen, and the blaring horns of The Emotions’ “Best Of My Love” fill the soundscape. Over the next three minutes, Anderson bombards the audience with a variety of tightly-choreographed camera moves. At times the camera pirouettes on its own accord, unmotivated by any character, movement or line of dialogue, documenting human interactions and embodying the haphazard paths of the characters. At other instances the camera darts across the room from one conversation to another, motivated by the subtlest motion, thus displaying Anderson’s visual acuity and his deftness in juggling the film’s numerous storylines. Throughout the shot, stunning moves — like the unexpected rolling tilt toward the Reseda marquee — signal a commitment to visual innovation in spite of the constant references to movies like “Goodfellas.” In just three minutes, Anderson boldly introduces the audience to eight characters and to the intoxicating nightclub lifestyle they live. In these moments, “Boogie Nights” — as a sprawling mosaic — is alive in long shot.

The film’s second notable oner is a microcosm of Anderson’s progression from fastidious visual stylist to hands-off (i.e., Altman-esque) observer of human interaction. Again, Anderson uses technical precision to display his skill as a director: As Eddie Adams arrives at Jack Horner’s house, the opening bars of Three Dog Night’s “Mama Told Me Not To Come” set a light tone that contrasts with that of the previous scene, in which Eddie fled his abusive home. This shift is echoed by the emergence from Jack’s under-lit house to the poolside exterior, which is bathed in the ethereal light of the overexposed sky. As Jack introduces Eddie to Buck Swope and Becky Barnett, the camera seems to float unmotivated. It circles around the group and back, with no particular relation to any of the dialogue, then moves backward, farther and farther from the group. The camera seems to lead the actors, rather than the other way around, as it is only after several seconds of this backward motion that Jack and Eddie turn to follow. Here Anderson once again displays his penchant for contrasting effects: Jack shouts to Reed Rothchild — who is off-screen and behind the camera — and the camera then whip pans 180 degrees and settles on Reed. In this instant Anderson inverts the shot’s style — the camera that seemingly dragged Eddie and Jack along is suddenly propelled by Jack’s words and movement. The ever-shifting levels of audiovisual dynamism Anderson creates keep viewers on their toes and lend a feeling of organic, lively messiness to “Boogie Nights.”

If the first minute of the “Mama Told Me (Not To Come)” shot brings “Boogie Nights” to life through dynamic movement, then the second minute does so through stasis. As Jack introduces Eddie to Reed as “the new boy on the street,” the camera arrives at a profile two-shot, where it will remain for the duration of the shot. Before, Anderson directed the audience’s eyes with camera movement; now, the viewer’s eyes ping-pong between Eddie and Reed as they converse. Free from stylistic distraction, viewers can bask in Reed’s bloviating stupidity and take pleasure in Eddie’s innocent, nervous desire to impress Reed. Anderson wisely encompasses the pair’s entire conversation — from margaritas and gyms to Reed’s (John C. Reilly) likeness to Harrison Ford — in a single shot. Thus, viewers get a sense of the conversation’s actual timing, awkwardness and humor, which serve as the foundation on which a very real friendship is constructed. Most importantly, Anderson steps back: it’s just Eddie, Reed and you, the viewer. The humanity of these characters can thus freely and directly call to the viewer. Whereas the first half of this shot creates a sense of life, the second half simply funnels it from screen to viewer.

This conduit becomes even more direct in later shots, as Anderson opts for a rougher-edged, handheld documentary style over the polished steadicam look of earlier shots. There is no better example of this shift than the film’s most heartbreaking scene, in which Dirk Diggler rejects Scotty J.’s sexual advances. This rough style perfectly complements Scotty J.’s poorly thought out plan — namely, to woo Dirk with his newly painted Datsun. Again, Anderson mixes motivated and unmotivated camera moves; yet, on the whole, the camera moves less in this shot than any of the previous long takes, spanning perhaps only twenty feet. Further, as opposed to the constant motion of the opening shot, the camera now moves from one point to another, deliberately settling at each spot to allow the drama of each beat to unfold. In addition to facilitating drama, this relative lack of motion allows Anderson to draw attention to the staging of his actors, thus complementing their performances. After Dirk rejects Scotty J., the two are framed in opposition: Dirk commands the foreground while Scotty J. is reduced in the background, emphasizing his vulnerability. As Scotty pleads with Dirk — “Please, can I kiss you on the mouth?” — and as Dirk walks back toward the house the pair are framed in a profile two-shot. At once, viewers can see both Scotty’s pain and Dirk’s confusion as Scotty scrambles, stammering, “I’m really wasted, I’m crazy right now, you know?” Now, the noticeable movement comes not from the camera, but from Scotty (as played by the great Philip Seymour Hoffman), who nervously grasps at his jacket zipper and fixes his hair as he explains in a last-ditch effort that he was planning on returning his new car if Dirk didn’t think it was cool. Hoffman is brilliant in this scene, and Anderson clearly knows it — like the viewer, Anderson simply watches Hoffman pour his soul into the scene.

And it works. The heart of “Boogie Nights” beats just as strongly during this understated scene as it does during the exuberant opening shot. I can think of few movies that display such delicate balance between stylistic flash and restraint.