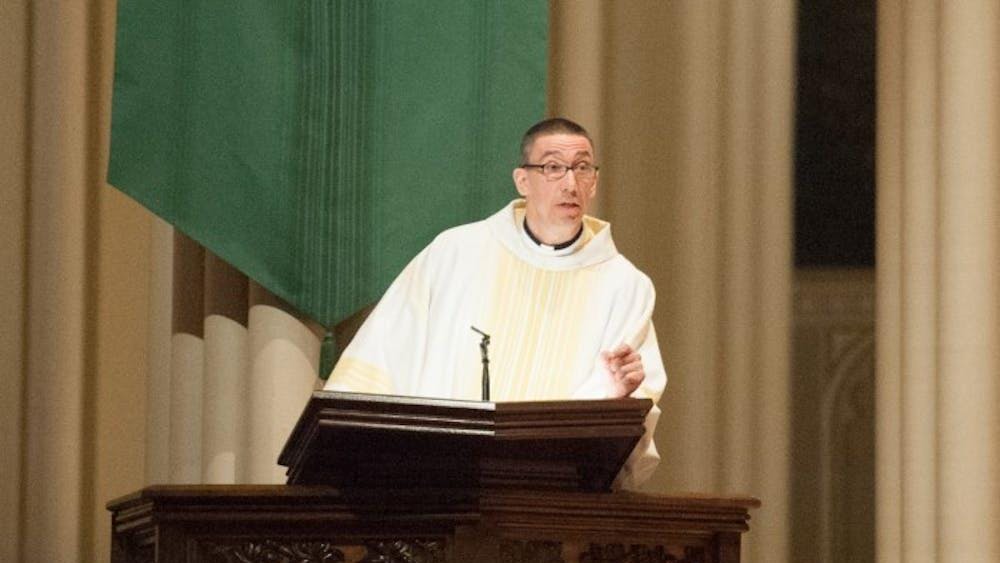

Professor Michael Waddell, director of the master of autism studies program at Saint Mary’s, called for a more complete understanding of autistic identities — acknowledging both the struggles and gifts of individuals with autism — during a presentation Wednesday.

In the lecture, Waddell read from his personal work exploring autism in relation to the Catholic faith and said he plans to publish a book on the subject in the future.

“The task of my book is to search Catholic intellectual tradition for resources that can enrich the way we understand and respond to autism,” he said.

Waddell opened his presentation by discussing autistic identity in context of the “Autism Rights” movement, which advocates for autism to be viewed not as a disability, but rather as a form of neurological diversity.

Members of the movement believe that, for those on the spectrum, autism is an intrinsic part of the self, Waddell said.

“Accordingly, the much-sought-after cure for autism has been condemned by some autistic self-advocates as an assault on a minority group that is akin to eugenics or genocide,” he said.

Waddell said he looked to St. Thomas Aquinas and his writings on the metaphysics of identity and relationships to gain insight into how those with disabilities form their identities.

He referenced a reflection on Aquinas’s writings by Fr. Terrence Ehrman, assistant director for life science research and outreach at Notre Dame, entitled “Disability and Resurrection Identity.”

Waddell said Ehrman “goes so far as to explicitly deny that disabilities are intrinsic to a person’s identity” and “rejects the notion that healing a disability would destroy an individual’s identity” in his article.

“Indeed in this way of seeing things, curing autism might even be thought to make a person’s life better,” Waddell added.

However, he said, advocates of autistic identity would strongly object to the idea that their condition is a privation, instead seeing it as an inalienable part of themselves.

Waddell said his research led him to view autistic identity as uniquely relational, defined by the way autistic individuals bond with one another.

While those with autism are often misunderstood as antisocial by nature, Waddell said, in reality, they can develop profoundly meaningful relationships if given the opportunity to freely interact with others like themselves.

“In this way, autistic identity is not merely a matter of being a subject of privation, or even a matter of a diagnosis — it’s an act of self-understanding that creates connections with others who become friends,” he said. “These relations that comprise autistic identity are real goods in the lives of autistic people.”

With this in mind, Waddell said, public discussion of autism ought to focus on both acknowledging the struggles life with the disorder brings as well as celebrating the unique minds of those who have it.

“I think that there’s room for meeting in the middle,” he said. “It allows us to have meaningful conversation in a way that’s not happening now.”

Waddell added that Catholic Social Teaching can provide insight into how dialogue between non-autistic individuals — so-called “neurotypicals” — and those on the spectrum can be achieved.

“Here I think the Catholic Church has even more resources to offer — teachings and practices about using power to serve those who are vulnerable, rather than to persecute them, about forgiveness and reconciliation in broken relationships, about understanding all people as having inherent identity,” he said.