In the late summer of 2015, Germany opened its borders to a large number of Syrian refugees who were fleeing their country for Europe. That policy choice has had many ramifications in the nearly three years since. In recent weeks, the city of Chemnitz in eastern Germany has seen an acute backlash against foreigners after two refugees allegedly stabbed a German man to death.

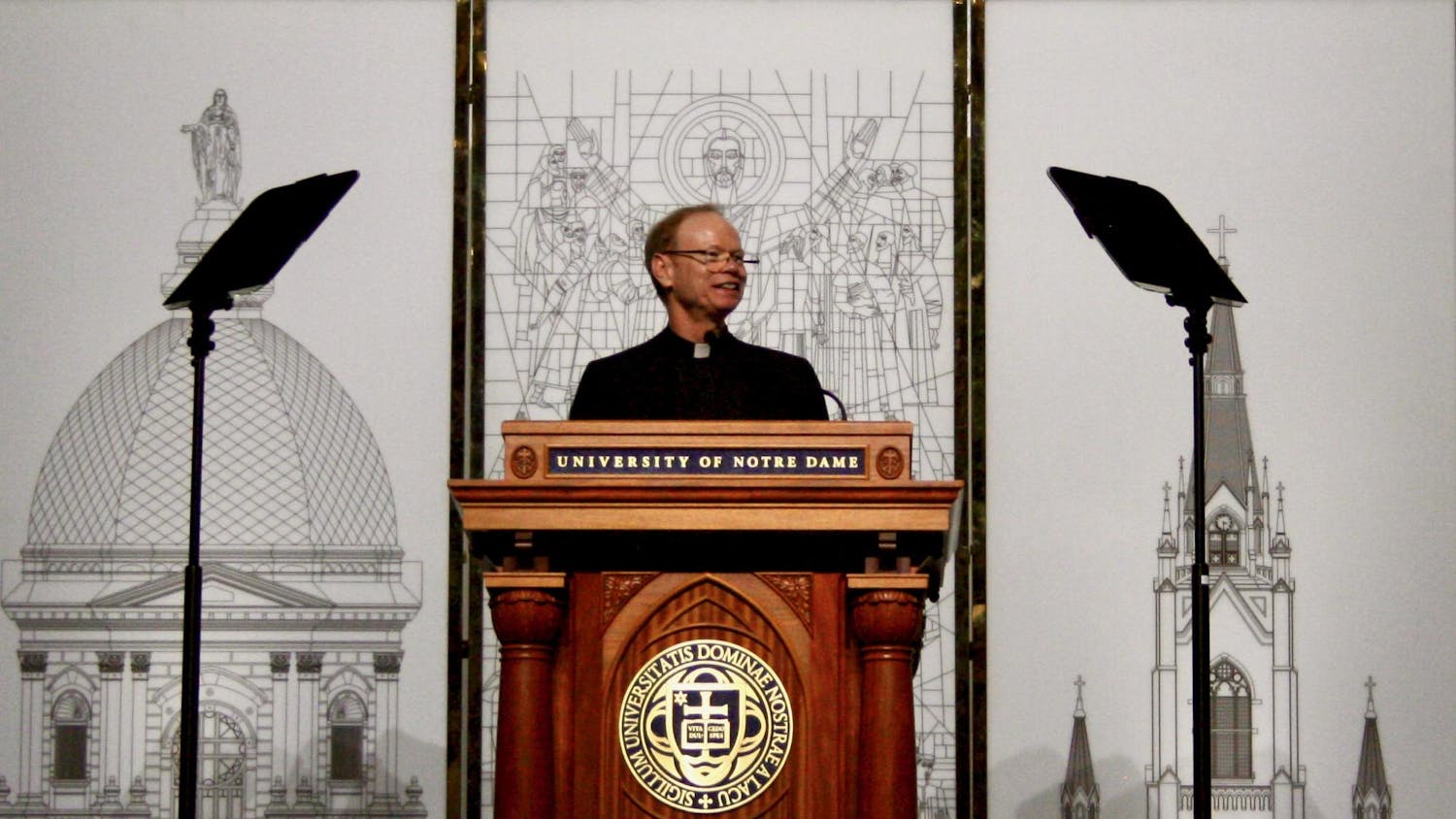

A panelist of six Notre Dame faculty members explored the forces at work in Chemnitz, Germany, and the West in a Tuesday panel discussion entitled “Lessons from Chemnitz: Right-Wing Radicalism in Europe Today.”

Maurizio Albahari, an associate professor of anthropology, noted the trend of illiberalism sweeping Europe. While he said the European far-right, with the help of former White House advisor Steve Bannon, is increasingly effective at campaigning, there are underlying issues that make Europeans susceptible to these arguments.

“Concerns about immigration often illuminate issues that predate immigration — regional hierarchies and inequalities, youth emigration, multiple forms of socioeconomic precariousness and nationalism,” Albahari said.

To demonstrate his point, Albahari described the situation in Saxony, the state in which Chemnitz is located. Though he said many residents cite the influx of foreigners as society’s biggest problem, most people have not had major interactions with foreign-born individuals. Most Saxony residents are also relatively satisfied with their lives. These facts, he said, point to the “saliency” of racism. However, Albahari expressed hope for the future, as he noted the many active anti-racist and anti-fascist groups in Chemnitz.

“If it is at the local and everyday level that national and supranational racism materializes, it is also at that very level that egalitarian integration and anti-racist engagement emerges with equal force,” he said.

Rüdiger Bachmann, an economics professor, explored how migration and related issues have affected the German political scene, particularly regarding the electoral ascendancy of the far-right, anti-immigrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) Party.

In exploring what kind of people vote for the AfD, Bachmann suggested history could play a role.

“Who votes for AfD? Who votes right-wing populist in Germany? That’s actually a bit surprising. A famous, current study … they actually find something super interesting, something that’s also slightly deviating from experience in other countries,” he said. “They actually found that the biggest explanatory variable for AfD vote shares is the vote shares of the Nazi Party in the early 1930s. This is controlling for influx of immigrants and unemployment rates, which sort of approximate local economic conditions, which actually didn’t have much explanatory power. So, this, if you believe these numbers, that shows there’s a deep undercurrent cultural streak of racism, anti-Semitism, in the vote shares of the parties.”

In discussing the current state of other major German political parties, Bachmann said longtime Chancellor Angela Merkel, who opened the borders in 2015, is in a weak position. He also said Germany’s two largest parties, the center-right Christian Democratic Union and center-left Social Democratic Party, are both in a precarious position. The AfD, he said, has placed second in recent opinion polls.

Bill Donahue, the director of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, said overall German attitudes toward immigration have soured in the years since 2015.

“When I compare mainstream news reports from a year ago to now, what you see is people who were basically pro-immigration, pro-integration are largely abandoning that stance. They’re abandoning it by taking cover under bureaucratic and logistical arguments,” he said.

While at one point many Germans saw the influx of immigrants as an opportunity, that idea has lost much of its popularity, Donahue said.

“In 2015-2016 … there was a bit of a honeymoon for German national identity. Contrary to what Fritz Stern argued about unification being Germany’s great second chance, it was really Merkel’s immigration policy that gave Germany its great second chance,” he said. “It revived German popularity, German reputation and essentially erased to some extent the image of Germany of former Nazis. That no longer seems to be paramount in the minds of Merkel’s critics, for all kinds of reasons.”

American studies professor Perin Gürel discussed the implications of these current problems for Germany’s Turkish community, which continues to be Germany’s largest ethnic minority. While the Turkish-German community has been vocal in its opposition to the backlash in Chemnitz, Gürel drew parallels between Germany’s experience with refugees and Turkey’s, noting that the latter is home to the largest number of Syrian refugees.

“In an online discussion, I was surprised to see — I don’t know why I was surprised — but it was shocking to see Turks express some anti-refugee sentiments that really parallel the German far-right,” Gürel said.

Vittorio Hösle, the Paul Kimball Chair of Arts and Letters, expressed a concern that it is becoming more difficult to have a rational conversation about the politics of refugees in Germany, noting there are “objectively” some issues that have been caused by the influx.

“What worries me is that it has become very difficult to discuss rationally the pros and cons of different policies,” Hösle said. “On both sides, there are certain stereotypes there. If you are critical of some of the decisions of Merkel, then you are adamantly a neo-Nazi, and on the other hand, if you are for universalist politics you are a traitor to your nation.”

Hösle offered some criticisms for how Merkel had handled the refugee situation, noting she did not consult the German parliament before deciding to open the country’s borders. He was also critical of the chancellor’s failure to set an upper limit on how many refugees she was willing to admit at the height of the crisis.

Jim McAdams, a political science professor and the director emeritus of the Nanovic Institute, said German political parties need to make changes in how they operate in order to connect with the types of people who vote for the far-right. He cited the example of people living in formerly communist East Germany, whose plight, he argued, is not well understood by those living in former West Germany and has led them to support the far-right.

“I think they need to do is begin to redefine themselves,” he said. “The challenge for parties in Germany is how to redefine their relationship with people who no longer trust them.”

Panelists discuss refugees, far-right in Germany

Annie Smierciak | The Observer

Six Notre Dame professors participated in a panel discussion Tuesday titled "Lessons from Chemnitz: Right-Wing Radicalism in Europe Today." The panel focused on the issues of refugees and the far-right in Germany.