The University of Notre Dame has historically been home to a predominantly white student body. Currently, both minority and international students comprise about 30 percent of its population. So it came as a shock to some when they discovered that the Snite Museum of Art would host “Solidary & Solitary: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection,” a traveling exhibit of abstract art from modern and contemporary artists of African descent.

The exhibit, on view until Dec. 15, draws from the collection of Pamela Joyner and Fred Giuffrida. The collectors will visit the Snite Museum of Art this Friday for a public reception with the exhibit at 5:30 p.m. that is free and open to the public.

“Solidary & Solitary,” which was curated by Christopher Bedford and Katy Siegel from the Baltimore Museum of Art, showcases just the tip of the iceberg of their vast collection — the exhibit in the Snite contains 51 pieces out of the almost 400-piece collection, including monumental works from Glenn Ligon, Shinique Smith, Norman Lewis, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, Jack Whitten and others.

In a phone interview with both collectors, Giuffrida, a ’73 Notre Dame alumnus, says that he and Joyner “don’t think of collecting as a passive activity. There is a mission behind the collection, and that is to rewrite history to put these artists in their proper place.” Instead of simply paying for pieces and not understanding the artists behind the work, Joyner and Giuffrida have developed a personal relationship with a majority of the living artists from the collection. The pair even own a property next to one of their homes in Sonoma, California, where artists are able to take up residency. Joyner believes this “is an opportunity where we get to know people personally and particularly with living artists.”

[gallery type="columns" link="file" ids="165165,165166,165153,165154,165156,165152,165155"]

Through this traveling exhibit, Joyner and Giuffrida are attempting to change the art world and influence the the future of art history. Within the art world, many of these artists have been forgotten about and strewn aside.

Joyner notes that, during the Harlem Renaissance, African American artists were expected to create art that displayed the struggles of fellow African Americans — but when they failed to do so, their art and talent was pushed to the side.

“On the one hand, the traditional art world did not assign validity to art created by African American makers that did not clearly depict African American subject matter,” Joyner, who began collecting in the 1990s, says. Joyner, who has spearheaded the couple’s collection project and now works full time as a collector, says that she became interested in abstract art because it offered “another way of making” for the artists. Now, through “Solidary & Solitary,” these abstract artists are receiving their long-overdue recognition.

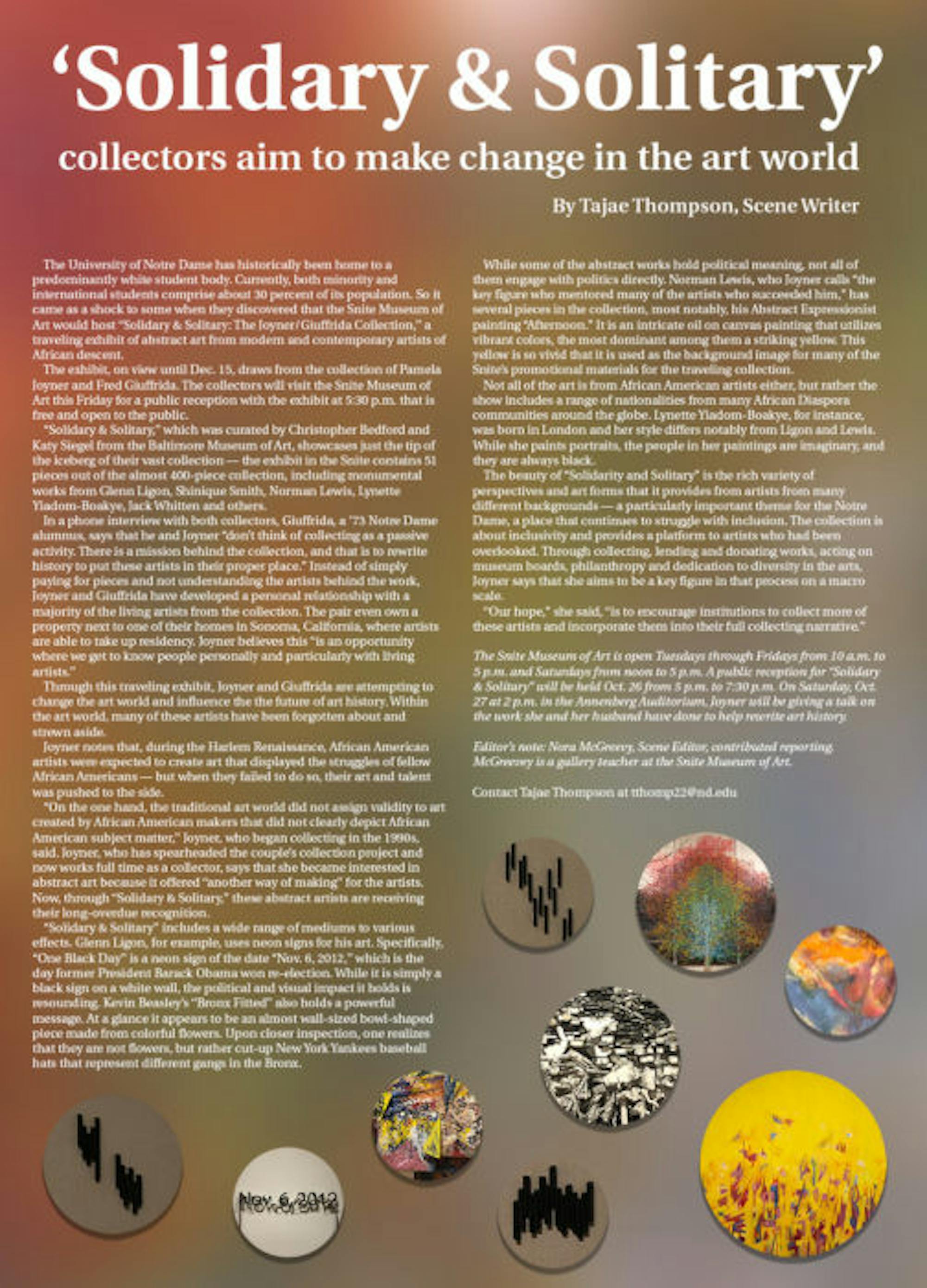

“Solidary & Solitary” includes a wide range of mediums to various effects. Glenn Ligon, for example, uses neon signs for his art. Specifically, “One Black Day” is a neon sign of the date “Nov. 6, 2012,” which is the day former President Barack Obama won re-election. While it is simply a black sign on a white wall, the political and visual impact it holds is resounding. Kevin Beasley’s “Bronx Fitted” also holds a powerful message. At a glance it appears to be an almost wall-sized bowl-shaped piece made from colorful flowers. Upon closer inspection, one realizes that they are not flowers, but rather cut-up New York Yankees baseball hats that represent different gangs in the Bronx.

[gallery type="columns" link="file" ids="165157,165158,165159,165160,165161,165162,165163"]

While some of the abstract works hold political meaning, not all of them engage with politics directly. Norman Lewis, who Joyner calls “the key figure who mentored many of the artists who succeeded him,” has several pieces in the collection, most notably, his Abstract Expressionist painting “Afternoon.” It is an intricate oil on canvas painting that utilizes vibrant colors, the most dominant among them a striking yellow. This yellow is so vivid that it is used as the background image for many of the Snite’s promotional materials for the traveling collection.

Not all of the art is from African American artists either, but rather the show includes a range of nationalities from many African Diaspora communities around the globe. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, for instance, was born in London and her style differs notably from Ligon and Lewis. While she paints portraits, the people in her paintings are imaginary, and they are always black.

The beauty of “Solidarity and Solitary” is the rich variety of perspectives and art forms that it provides from artists from many different backgrounds — a particularly important theme for the Notre Dame, a place that continues to struggle with inclusion. The collection is about inclusivity and provides a platform to artists who had been overlooked. Through collecting, lending and donating works, acting on museum boards, philanthropy and dedication to diversity in the arts, Joyner says that she aims to be a key figure in that process on a macro scale.

“Our hope,” she says, “is to encourage institutions to collect more of these artists and incorporate them into their full collecting narrative.”

The Snite Museum of Art is open Tuesdays through Fridays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and Saturdays from noon to 5 p.m. A public reception for “Solidary & Solitary” will be held Oct. 26 from 5 p.m. to 7:30 p.m. On Saturday, Oct. 27 at 2 p.m. in the Annenberg Auditorium, Joyner will be giving a talk on the work she and her husband have done to help rewrite art history.

Editor’s note: Nora McGreevy, Scene Editor, contributed reporting. McGreevy is a gallery teacher at the Snite Museum of Art.