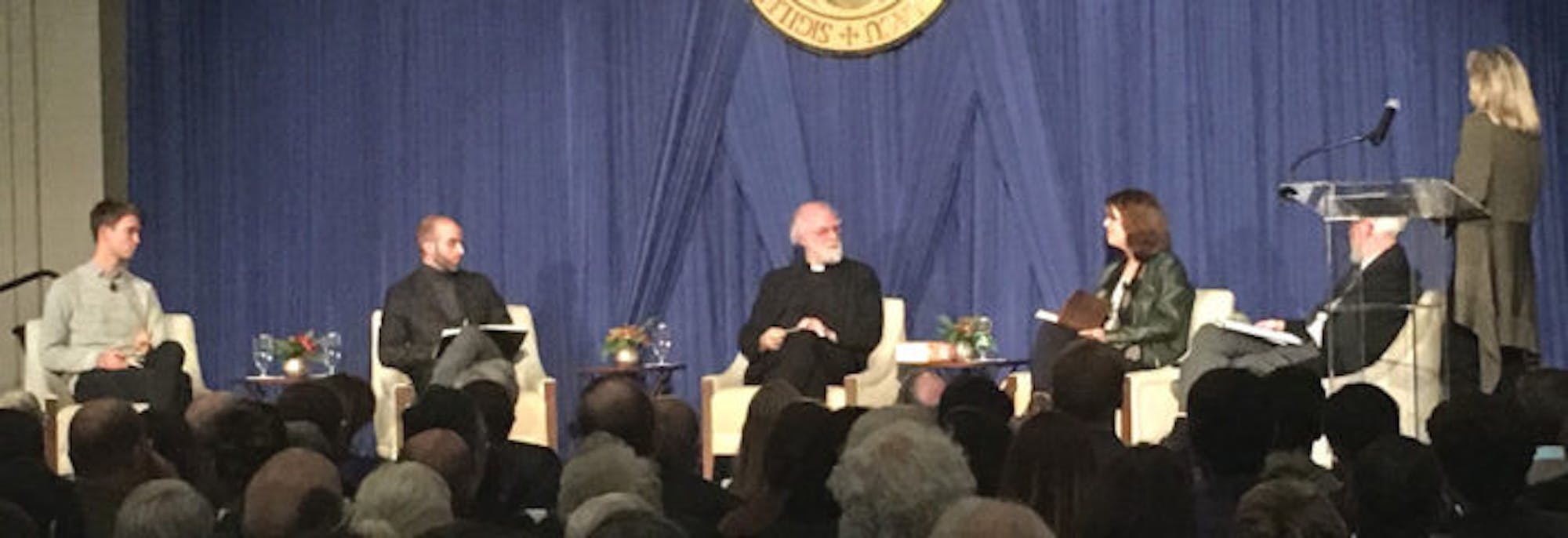

Former archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams discussed the portrayal and power of prayer in Shakespeare’s work in a lecture in the Dahnke Ballroom as part of the Notre Dame Forum on Monday night.

Though Shakespeare’s works cover a broad range of topics — including comedy, tragedy, love, deceit and death — there are some themes and issues that appear consistently. Williams said prayer is one of these recurring themes.

“One of the most characteristic features, in fact, of Shakespeare’s dramatic work is the way in which he will allow his plays to talk to each other,” he said.

Though prayer is visible throughout Shakespeare’s work, Williams specifically addressed its portrayal in Shakespeare’s plays written between roughly 1599 and 1611 — plays such as “Hamlet,” “Henry V” and “The Tempest.”

Each of these plays contain characters praying, or attempting to pray, Williams said. In “Hamlet,” Claudius attempts to pray for forgiveness for killing his brother — Hamlet’s father — while at the same time hypocritically continuing to enjoy the throne he gained as a result of his brother’s murder. In “Henry V,” the eponymous king of England prays for victory against the French, while at the same time acknowledging that his position as king results from his father’s potentially illegitimate usurpation of the throne.

“We are left with a whole set of unresolved questions about prayer. What makes it effectual? What renders it ineffectual? And about whether interior penance is actually the whole story,” Williams said. “The echoes are clear — here again is someone praying to be able to repent while not having to make restitution of the goods he enjoys in virtue of the sin for which he is trying to repent.”

The prayers offered in these are not always entirely genuine, Williams explained, as Shakespeare stages them for the effect they may supposedly produce. In the play “Measure for Measure,” a similar dynamic is on display in which various characters feign sincerity in order to manipulate others.

“Appeal is constantly being made to mercy, to grace and yet the characters, each one of them in their different ways, pretends to seize that mercy and use it as a tool of control, of staging, of pushing others into roles and patterns of interaction — dramas — that the powerful ego sets out to construct,” Williams said.

In “The Tempest,” Shakespeare’s final work, the dynamic is slightly different. The wizard Prospero, who throughout the play has used his magic powers to manipulate the other characters to achieve his own goals, lays down his instruments of power and vows his days of magic are over.

“He is stepping out of the role of being a dramaturgist, he’s stepping away from the power to do what the Duke in ‘Measure for Measure’ does, what Hamlet and Claudius are both doing, what in a sense Henry V, too, is doing,” Williams said. “That is, the attempt to resolve, or bring truth to light, by staging a performance. Prospero has, unlike the others, succeeded in his task. He has staged something which has brought about not only truth but a certain kind of reconciliation.”

Prospero abdicates his power in an attempt to reconcile himself. He appeals to the audience in “The Tempest,” saying, “Unless I be relieved by prayer, which pierces so that it assaults, mercy itself and frees all faults, as you from crimes would pardon'd be, let your indulgence set me free.”

“It is a renunciation that he cannot simply make for himself,” Williams said. “He needs prayer — not his own prayer, not the elusive, transparent, totality of repentance which escapes all the characters we’ve seen so far, but something else. He needs the audience, he needs the redeemed human community.”

It is this moment, Williams said, that speaks to the audience.

“In that moment of seeing the staging of our own despair, our own unwillingness to renounce and be transformed — as we see the staging of that we understand the depth of our own need,” he said. “As we let go of the characters on stage, the characters in the drama, we enact, we stage, what we need to do for one another, and what God has done in his own theo-dramatics with us, is to breath freedom for creatures, freedom for the other and in that prayer is justified, and prayer is answered. We are relieved by prayer.”