Power outage fuels campus chaos

April 26, 1999 | Finn Pressly and Tim Logan | Researched by Sarah Kikel

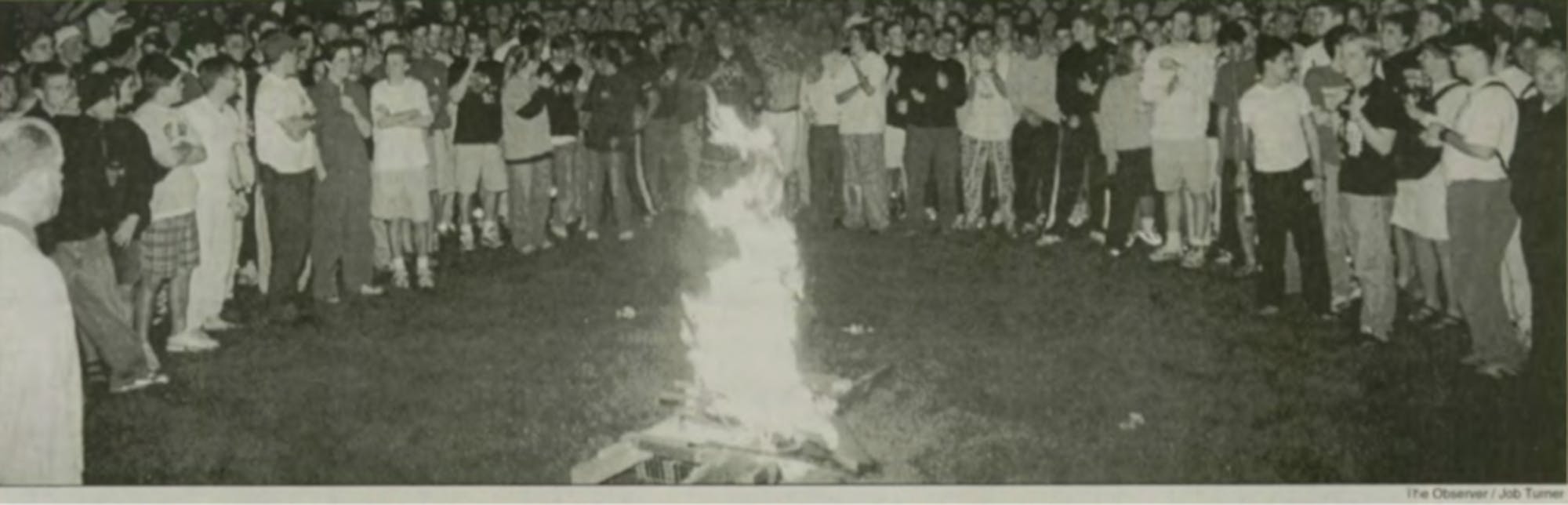

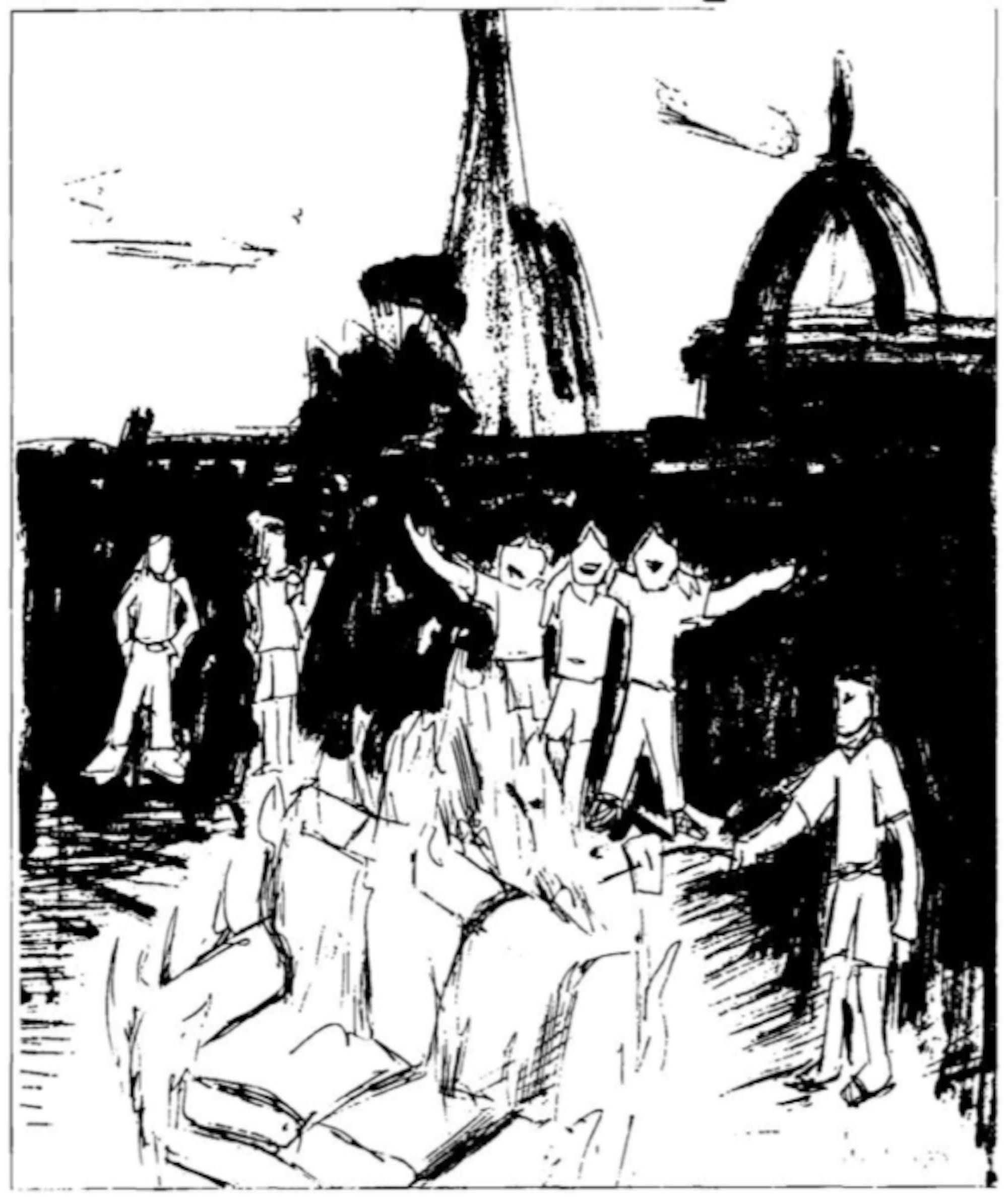

At approximately 1 a.m. on April 26, 1999, a power outage affected the north side of South Bend, including the Notre Dame campus. Most campus buildings, including every residence hall but McGlinn, lost power. The outage was caused by a partially-severed Indiana-Michigan power supply line, which director of University security Rex Rakow later said he suspected was due to a raccoon chewing the line. While the lights came back on after approximately 40 minutes, the commotion on campus continued into the night — now student-led.Students ignited six bonfires across campus, many of which grew out of control: One at Main Circle set fire to a nearby tree, and flames in front of Fisher Hall reached up to 12 feet high.

Students respond to ‘Black Sunday’ events

April 28, 1999 | Researched by Andrew Cameron

In the wake of the April 26 power outage and ensuing uproar, students weighed in on the night’s events in The Observer’s April 28 Viewpoint section. Responding to widespread criticism of the night’s unruly behavior, sophomore Michael Cory Campbell defended the students involved.“[The students] were not violent or angry,” he wrote. “They were just enjoying a great part of life: chaos. Ironically, what posed the greatest danger was the University’s attempt to actively control chaos.”Campbell cited a fire truck refusing to yield to pedestrians and a fire extinguisher “hurl[ing] noxious chemicals into the crowd” as examples of the University’s response endangering students.Junior Mike Major, coining the term “Black Sunday,” had a less favorable view of the students’ revelry.“Never before in my three years as a student have I been so ashamed of the Notre Dame student body,” Major wrote. But his reasons for disapproval were unusual: “Do we really consider that a riot?”

Office of Residence Life responds to student uprisings

May 14, 1999 | Tim Logan | Researched by Meg Pryor

On May 14, 1999, The Observer ended its Black Sunday coverage with news of its consequences: Several April 26 “rioters” would appear in hearings with the Office of Residence Life. Despite the sizable crowds, reports were filed for only 12 students. Following their hearings, the students would be disciplined on the basis of “obstructing police and fire officials, adding fuel to bonfires and disrespecting security personnel.” The hearings would not be held until the following semester, however, because the disciplinary reports were not filed or reviewed until after classes had ended. University policy dictates that hearings may not take place during finals week. Representatives of the Office of Residence Life expressed hope that the disciplinary process could remind students of the University’s behavioral expectations.“I think you could say our process is a way to educate people of our standards,” said Jeffrey Shoup, the director of Residence Life. “This is a way to re-educate people about what is appropriate and what is inappropriate.” While the names of disciplined students and details of the hearings were never released, the strange story of Black Sunday still persists — perhaps just as captivating today as it was on that fateful night in 1999.