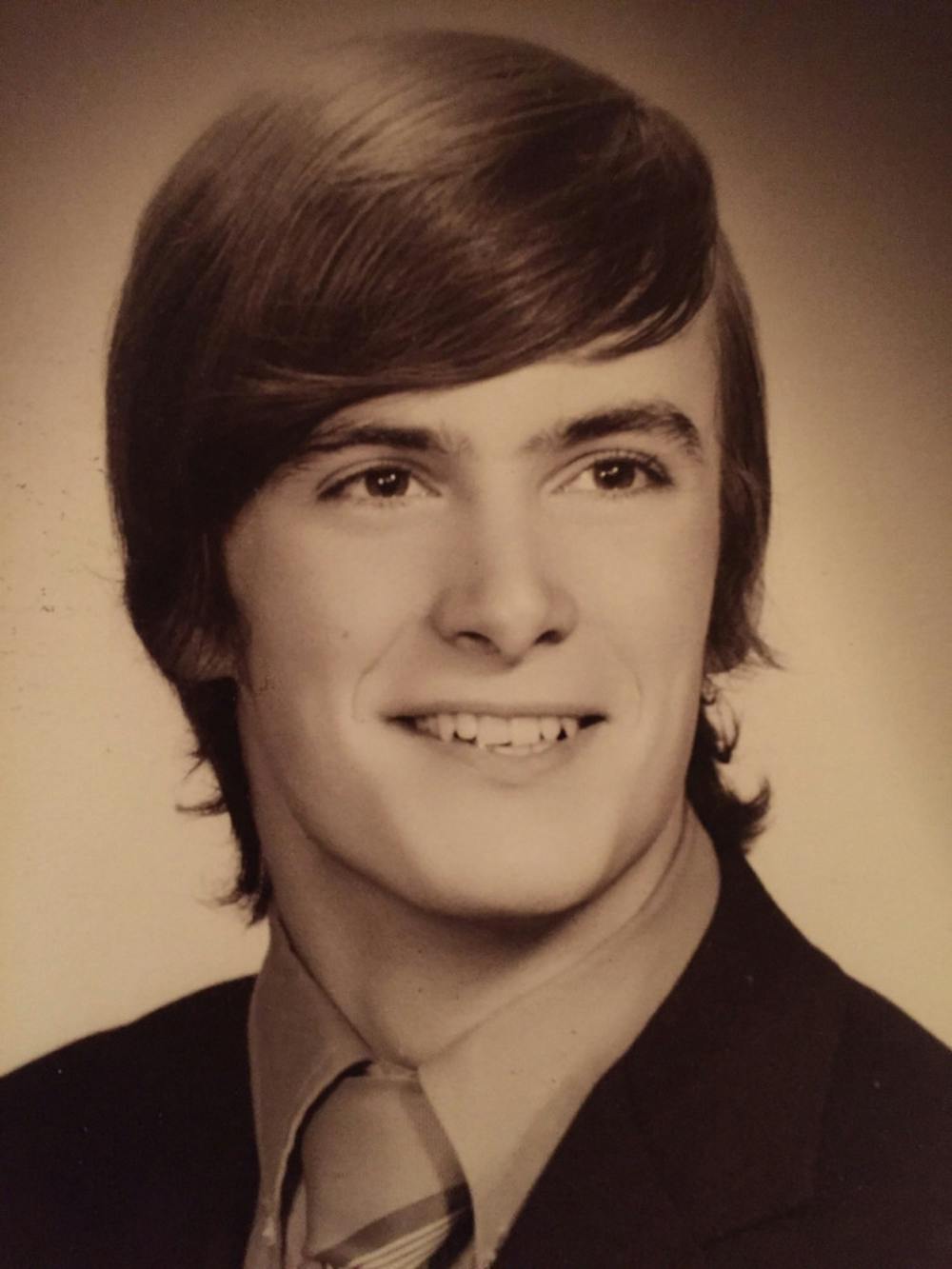

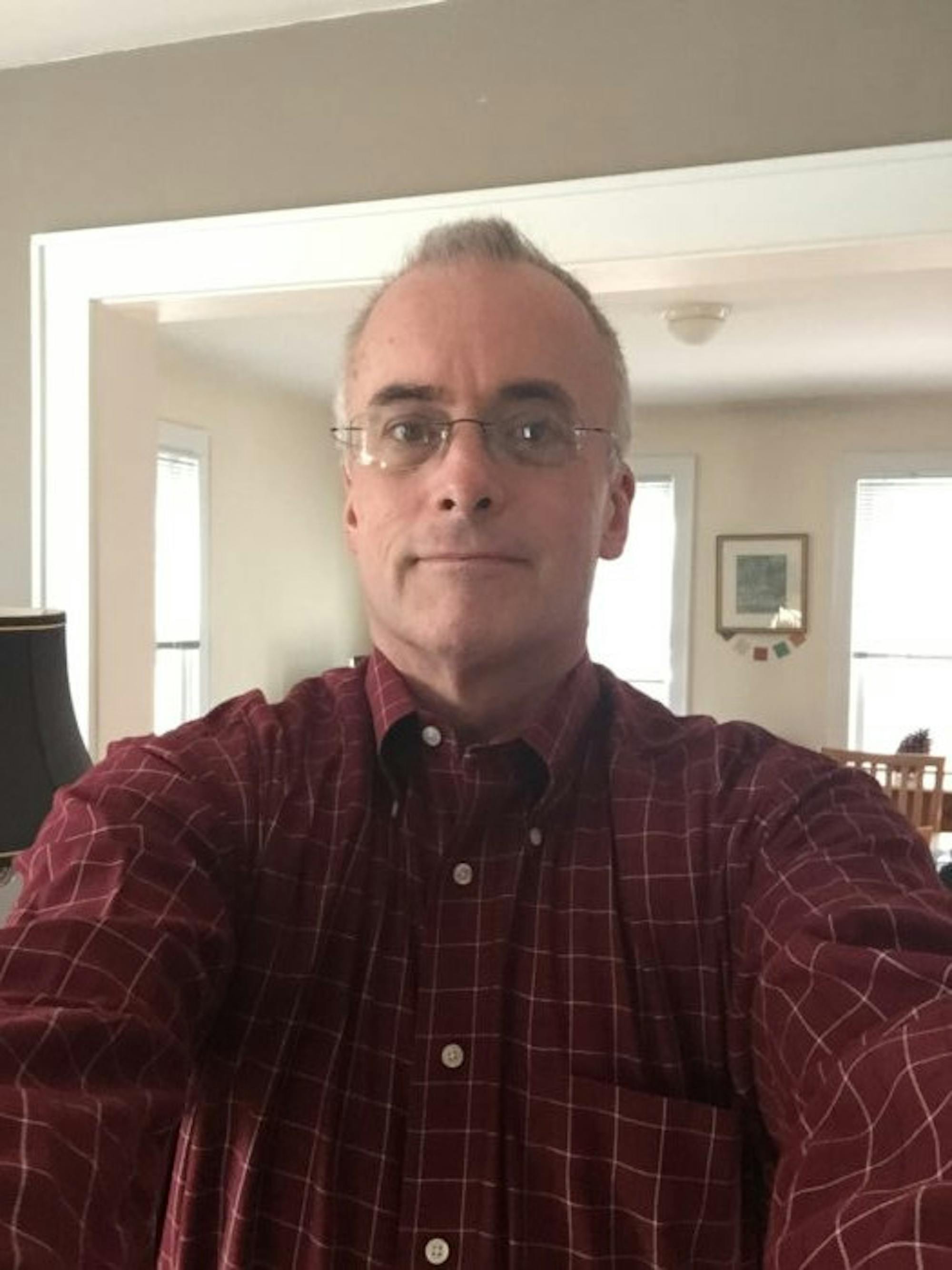

Mark Fuller, class of 1977, came forward with his experience of priest abuse in 2002. Notre Dame offered little more than an apology.

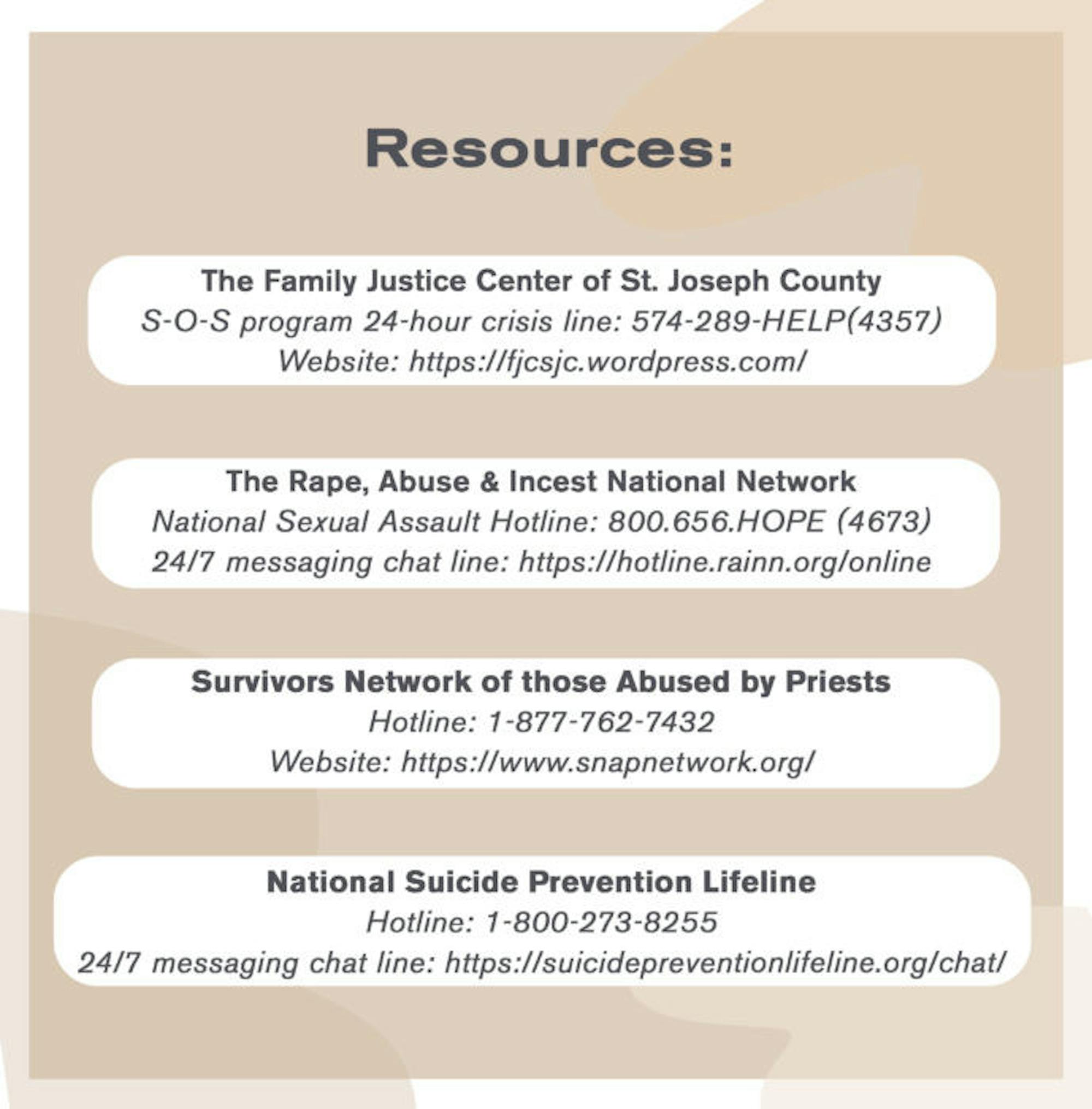

Editor’s note: This story includes descriptions of sexual abuse and violence. A list of sexual assault reporting options and on-campus resources can be found on the Notre Dame, Saint Mary’s and Holy Cross websites.

The first two times Mark Fuller visited Fr. William Presley, then rector of St. Edward’s Hall, they just talked. It was 1974, and Fuller vividly remembers sitting in an orange lounge chair in the front of Presley’s rectory while the priest asked him questions about his classes, his family and his personal life. Fuller remembers Presley offering him a soda.Then, in their third or fourth meeting, Fuller said, things changed. Presley told Fuller to wait while he went into the bedroom. When Presley called him in, he was in bed under the covers. He told Fuller to disrobe.Fuller said this was the first time Presley raped him.“He would go get a washcloth — ‘This is what you do. This is what you do with your partner,’” recalled Fuller, 65. “He was telling me how sex worked.” Presley raped him two more times during his sophomore year, Fuller said.Investigators say Presley victimized many people over the course of his career. According to a 2018 report by a grand jury that investigated sex abuse allegations against the clergy in Pennsylvania, where Presley also worked, at least five have credibly accused him of abuse. The report, which cited records from the Diocese of Erie, said Presley was known to have abused people through “‘choking, slapping, punching, rape, sodomy, fellatio, anal intercourse’ and other acts.”“It’s some kind of a soul murder, you know,” said Fuller, who graduated from the University in 1977. “It really is. It damages something so important that you can’t see.”Since the grand jury report was made public in August 2018, Notre Dame has developed several initiatives addressing the Catholic Church’s sexual abuse crisis. The University commissioned two task forces, one to facilitate dialogue on campus, another to assess research opportunities. It pledged up to $1 million to fund research on clergy abuse. The University even hosted its 2019 Notre Dame Forum on the subject.

However, there has been little public discussion of Notre Dame’s own history with abusive clergy in recent years, and its own record with priest abuse remains murky. A 2003 report from the South Bend Tribune said at the time Notre Dame was aware of allegations against four priests. It is unclear if Presley, who was later defrocked and died in 2012, was one of them. Survivors like Fuller question whether the University has offered a full accounting of the cases involving clergy at Notre Dame. And, with little more than an apology decades after the alleged abuse, some, like Fuller, are left with a sense of unfinished business — which they say reflects a larger failure by the University to address the harm students suffered at the hands of its priests.The Observer asked Notre Dame how its strategies for abuse response and prevention have changed since the ’70s, particularly in light of the abuse crisis. The University did not respond and did not answer a question about how many priests working at Notre Dame had been accused of abusing a community member during their tenure.In the Presley case, Fuller reported the abuse to Notre Dame in 2002. In a statement to The Observer, vice president for public affairs and communications Paul Browne linked to an Associated Press article from 2003, where the University offered an apology to Fuller.“While we had no contemporaneous reports on file from that period, Notre Dame in 2002 reported the allegations against Presley to the Erie, Pennsylvania, diocese,” Browne said in a statement to The Observer. “The University publicly apologized to the student in 2003.”The University’s apology did little to assuage the pain Fuller has felt for nearly half a century, he said. For almost 30 years, he had refused to report Presley’s behavior to Notre Dame — largely, he said, because of a mix of fear and shame.In a series of interviews with The Observer over the past five months, Fuller shared his account of how the abuse he endured shaped his life, his faith and his perception of the university he once called home. He did so, he said, in the hopes that other survivors of clergy abuse — both at Notre Dame and elsewhere — might find the courage to share their stories. And he said he also hopes that his story might compel the University to reckon more fully with the sins of the priests from its past.

Grooming and abuseIn the fall of his sophomore year, Fuller and his roommate were invited to a football game watch party with Presley in St. Edward’s Hall. Presley was friendly, Fuller recalled of their first meeting. There were about a dozen students crammed into the rectory watching the game. Returning for his second or third game watch, Fuller said he decided to stay behind to talk to Presley. Fuller disclosed that he was gay, and he wanted to try conversion therapy to see if he could turn himself straight. “My church, my family, everything, everybody said that I was bad,” Fuller said.Presley was quick to offer help. He told Mark he would be his counselor.Fuller left the rectory that day feeling relieved. He had been praying to find someone to help him.“I thought God had presented this guy,” he said.Presley came to Notre Dame from the Diocese of Erie, Pennsylvania, in August of 1970, according to the grand jury report, which lists him as a “graduate and student counselor” at the time. According to The Observer archives, he was named rector of St. Edward’s Hall in September 1971. Universityrecords also indicate he was a member of hall staff in Keenan Hall. The grand jury report found that Presley’s track record of abuse began as early as 1963. The report concluded the Diocese of Erie knew of allegations against Presley by at least 1987.“Not speaking specifically about this case, every allegation that we had on file has been reported to civil authorities, whether it is beyond the statute of limitations or not,” Diocese of Erie director of communications Anne-Marie Welsh said in a statement to The Observer. “We will continue to report new allegations as they are made known to us.”Presley was defrocked in 2006. He died in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in 2012.

‘The color all went out of my life’Fuller and Presley stayed in contact for the remainder of Presley’s time at Notre Dame.Over the course of Fuller’s sophomore and junior years, Presley took him on trips around the country.In New York, Presley took Fuller to his first pornographic film, as well as to the Rainbow Room, a famous lounge in Manhattan.“I can’t even walk by that building without feeling sick to my stomach,” Fuller said.Fuller said during these trips, Presley often tried to initiate unwanted sexual contact with him.“He would touch me or touch my back, touch my arm, touch a leg,” he said.Presley also took Fuller to a ranch on the west coast. While there, Fuller said, Presley hired women sex workers for them.“I was so terrified and so disgusted … and just frozen. I couldn’t wait to get out of there,” Fuller said.He bought Fuller a stereo, speakers and a turntable. Disgusted by the gifts, Fuller gave them to his cousin as soon as he left college.“I think he was buying my silence,” Fuller said. Grooming victims and convincing them the abuse is a form of counseling or education is one way offenders can hold their victims psychologically hostage, convincing them to stay in an abusive situation, said Carlos Cuevas, a clinical psychologist and professor at Northeastern University. He declined to speak to the specifics of Fuller’s case but discussed the general dynamics and effects of sexual abuse.“Those are things that may not be physically keeping the individual from leaving, but certainly psychologically are making sure the offender can continue to have access to them,” Cuevas said. Sophomore year, when the abuse started, Fuller’s grades plummeted.Fuller’s friendships from freshman year also faded, and he withdrew from his extracurriculars. He wanted to drop out of school, but his father asked him to stay. “The color all went out of my life, you know, out of that campus,” he said. “It was no longer so beautiful to me.”Presley left Notre Dame in 1976, Fuller’s junior year.

Reporting the abuseAccording to 2019 correspondence between Fuller’s lawyer, Richard Serbin, and Notre Dame general counsel Marianne Corr, Fuller kept in contact with the University for at least a year after reporting the abuse in 2002.During that time, University records indicate Fuller corresponded with former Notre Dame general counsel Carol Kaesebier and Fr. Richard Warner, then chief adviser to University President Emeritus Fr. Edward A. Malloy. Fuller does not have records of his correspondence with Warner and Kaesebier from the early 2000s.According to University records, Fuller met with Notre Dame in April of 2003. His sister Paula Mason and a close friend, Carol Smola, came along for support.Kaesebier, Warner and other top University administrators attended on behalf of Notre Dame. Kaesebier was part of a three-person committee Malloy founded that year to work with survivors of abuse by Notre Dame clergy.Fuller hoped his meeting with the University would help him heal. He said he asked the University to help pay for him to receive an additional degree, as he felt Notre Dame had not given him the education he had paid for.“‘You put me through some more school, help me get a degree in counseling or be a therapist, and I’ll go help people like me,’” he said. “That’s exactly what I said.”Both Smola and Mason confirmed Fuller asked the University for help with education costs at the meeting. However, the University did not fulfill his request. In an email, Kaesebier said she did not recall enough about her correspondence with Fuller or the events of the meeting to comment. Malloy said he did not remember Fuller, and Warner did not respond to multiple interview requests.In reaching out to the University for comment, Observer reporters also asked University spokesperson Dennis Brown to confirm whether Fuller asked for help with educational costs or made any other requests during the meeting. The University declined to comment.According to University records, Fuller did not stay in contact with Notre Dame after the meeting.In an Associated Press article from March 2003, the University offered a public apology to Fuller for a priest who “had sexual contact with him” while he was a student there. “We feel very bad about this,” Fr. Richard Warner, at the time director of Campus Ministry and counselor to Malloy, said in the article. “We feel even worse because … he’s lived with it quietly for all those years and has had to seek out counseling. It wasn’t brought to our attention until almost a year ago.”The article does not identify Presley as the priest in question.Fuller said he was disappointed by the apology and feels the University has yet to take full responsibility for Presley.

Addressing the pastIn February 2019, the Diocese of Erie launched a survivor compensation fund. Fuller hired a lawyer and filed a claim, settling later that year. A third of Fuller’s settlement went to his lawyer, and another third went to taxes, he said. “It was by no means — originally or the part [of the sum] that I netted — enough for the medications, the therapy, the missed wages, the pain and suffering, nowhere even close,” Fuller said. “I can’t even do the math.”Fuller did not disclose the amount of the settlement. The diocese had also previously offered Fuller money for counseling, but it was only enough to cover about six sessions, he told media outlets during a demonstration in Pittsburgh led by the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests (SNAP), an international advocacy group of which Fuller is a member.However, Fuller did credit then-Bishop Donald Walter Trautman of Erie, Pennsylvania, for believing him when he reported Presley.According to news outlet goerie.com, in December, the compensation fund had paid a total of $5.9 million to 50 survivors, making the average settlement $118,000. Sums have ranged from $5,000 to $400,000.“Establishing a fund, handled completely independently by a third party, allowed us to publicly acknowledge the crimes of the past and the damage that was done,” Welsh said in a statement to The Observer. “It also gave us a way to offer some measure of justice to victims.”The diocese also offered to connect survivors with pro bono lawyers unaffiliated with the diocese’s law firm to help them through the process.Fuller’s lawyer, Richard Serbin, has represented over 400 child sex abuse survivors over the span of more than three decades. Serbin said in that time, he has seen a change in the Catholic Church’s approach to addressing sexual abuse.“In the early years when I was doing this, it was all hardball legal tactics, very aggressive tactics to fight these lawsuits,” he said.Since the early 2000s, the Catholic Church has made strides in addressing the sexual abuse crisis. However, the absence of greater regulation means there is still little consensus on what qualifies as adequate response and prevention, advocates said.Terry McKiernan, co-founder of the clergy abuse watchdog group called Bishop Accountability, said Catholic organizations should ensure comprehensive information about their abuse history is publicly available. This could include what the organization has done or is planning to do to address abuse, as well as a public apology to survivors, he said.“The message should absolutely be that the person at the top is willing to sit down with anyone who has been harmed,” he said.Former FBI executive assistant director Kathleen McChesney, who helped spearhead the creation of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops’ Office of Child and Youth Protection in the early 2000s, recommended Catholic institutions strengthen their abuse prevention with regular background screening, increased supervision and timely response to boundary violations. “You want to do everything you can to identify who’s an abuser,” she said.The University should do more to educate students about the dangers of clergy abuse, Fuller said. He suggested inviting survivors like him or other professionals in the field of abuse prevention to come speak to Notre Dame freshmen.“Be warned,” he said. “Be aware.”

‘There’s a progression; you can’t push yourself’As Fuller, now 65, nears retirement, he hopes to buy a small home, perhaps a townhouse. In his ideal world, Fuller would retire by a lake and perhaps find a significant other.“I know what I think and feel,” Fuller said. “I’m aware. And that is good for communicating.”Smola described Mark as “incredibly courageous” and “resilient” as she’s watched him heal throughout the years.“All of those talents and abilities ... that he’s had, he’s needed to use those to process through and keep going and accomplish all that he has,” she said.Throughout it all, he’s relied on family and friends, especially his sister.“We’re best friends today,” Mason said.Besides SNAP, Fuller is also a member of AlAnon, a recovery group for friends and family members of alcoholics. Daniel Wilson, one of Fuller’s friends from AlAnon, said he has also seen Fuller become increasingly open to sharing his story with others in the roughly 12 years they’ve known each other.“In our circle of friends in recovery, there are a lot of people who have suffered sexual abuse, both men and women, both straight and gay, and I think his experiences have helped people who have a different profile,” Wilson said.

Fuller rediscovered his lawyer’s correspondence with Notre Dame general counsel Marianne Corr from 2019 during an interview with The Observer. In the correspondence, Corr said she would be open to continue working with Fuller. He reached out to Corr in May, and the two have been in conversation.

At the beginning of Lent, a volunteer came to Fuller’s work offering to place ashes on people’s foreheads. Though his relationship with the church has been damaged, he decided to take ashes that day.“I didn’t lose all my faith,” Fuller said. “Still pray.”It takes time to process trauma, Fuller said, and he’d like to see more survivors have access to professional therapy.“There’s a progression; you can’t push yourself,” Fuller said. “You can’t rush too much, you can just get hurt again in a way, in weird ways.” And, he added, if he could talk to a young survivor, he’d like to offer them hope.“I would want that person to know — to be encouraged — that it sometimes gets dark or hard,” Fuller said.He paused.“And then it gets lighter.”