Carroll Hall votes to abolish parietals, commits to campus-wide protest

Jan. 31, 1979 | Mark Rust | Researched by Jim Moster

In January of 1979, the residents of Carroll Hall voted to abolish parietals in a move that sent shockwaves through the on-campus community. What started as an expression of frustration would go on to spark weeks of debate on residence hall visitation rules.

At the heart of the residents’ complaint was a feeling that Notre Dame did not treat them like “adults.” The infantilizing nature of parietals created an “unhealthy” social atmosphere, the Carroll residents claimed.

The residents were initially open to compromise. They pointed to Memphis State, where each hall has jurisdiction over its own visitation rules, as an exemplar of on-campus living.

It was the University administration, they argued, who was the problem. Provost Timothy O’Meara rejected a proposal to “place parietals in the jurisdiction of hall judicial boards,” leaving Carroll residents with the nuclear option of protest.

At a Monday night Hall Council meeting, the motion to abolish parietals passed with great enthusiasm. The sponsor of the motion, Mark Mocarski (’81), said that Carroll’s decision was just the beginning. The residents planned to organize and publicize a “parietals break night” involving the entire campus.

Carroll rector Brother Frank Drury was not impressed. There is a “good purpose” to University rules, Drury said, and their vote “doesn’t change anything.”

Drury cited evidence of his own in favor of parietals, arguing that students attending schools with parietals policies — such as Eastern Michigan University — found freedom in the visitation restrictions. “[Eastern Michigan University students] had parietals,” Drury said, “and their roommates didn’t have to worry about how they were attired or who came in their room after a certain hour.”Regardless, Carroll residents felt a need to take action — and other residence halls would come to agree.

Carroll Hall resident speaks out, offers student perspective on parietals reform

February 8, 1979 | Scott Rueter | Researched by Sarah Kikel and Uyen Le

Ten days after Carroll Hall’s Hall Council passed their motion to abolish parietals, Carroll Hall sophomore Scott Rueter (‘81) wrote a Letter to the Editor explaining the reasoning behind the dorm’s proposal.

Rueter made sure that his stance was apparent from the beginning.

“I, personally, am totally against parietals,” Rueter wrote. “I just do not like them.”

Rueter addressed the opposing argument — that parietals provide privacy to residents of each dorm — by questioning why privacy was only thought to apply to members of the opposite sex. As a better solution to ensuring privacy, Rueter suggested using the door locks attached to each dorm room instead.

He then moved on to counter the complaint that removing parietals would eliminate the ability of residents to walk around their dorms nude.

“I’m not particularly enthused about seeing naked guys walking around my hall,” Rueter wrote. “Also, what makes 2:00 or 12:00 the magic hour for a person to say, ‘Hey, I wanna go to the john naked!’”

Rueter dismisses this fear by proclaiming that he had never had the ill fortune of encountering any dorm mates dressed indecently.

“In fact,” he added, ”I have yet to see someone here [go] to the restroom with anything less on than what they might wear in public.” Then there was the stance that roommates should be able to enter their rooms without accidentally “‘interrupting’ something,” a point Rueter was quick to refute.“This means that the reason for parietals is that the administration is afraid of students engaging in sexual activity,” Rueter wrote, “which is also, well, dumb.” He followed this statement by cleverly explaining to parietalphiles that simply being present in someone else’s dorm room does not necessarily lead to sexual activity — if it did, there would be quite a lot of sex on campus. “[S]omeone who has sexual relations with everyone who enters his or her room is extremely prolific,” Rueter wrote. Even if this were the case, Rueter said students did — and would always — find ways around Du Lac guidelines. “What can be done after 2:00 that can’t be done before 2:00?” he asked. And in response to Carroll Rector Frank Drury’s comments emphasizing the importance of adhering to authority, Rueter asserted the necessity of change. “If you don’t like something, there is this thing called change,” he wrote. “Remember change? I think the founders of our country thought a little bit about it too. Maybe that’s a bit dramatic, but it does get my point across.” Insisting that the abolishment of parietals would not cause Notre Dame to descend into debauched chaos, Rueter contended that more lenient visitation policies would allow students to form responsibility and decision making skills without fear of severe punishment. “[Notre Dame] will still be a Catholic university — the guidance will still be there,” he wrote. “Moral values may be instilled within us, but they should not be forced upon us.” Finally, Rueter clarified what his vision of parietals reform looked like. “What we advocate here at Carroll is not necessarily a total abolition of parietals, but what we really want is the chance for ourselves to decide,” he wrote. “It should be a matter of the individuals within each hall to decide what restrictions they want on their own communal lifestyle. Rueter’s vision included some halls maintaining parietals, others adopting 24-hour visitation and the rest embracing a hybrid model. For his own community in Carroll Hall, Rueter proposed a hall-wide vote on visitation policies, followed by a trial period and a year-end review of the policies’ success.Ultimately, Rueter argued for heightened trust and acknowledgement of students’ maturity from Notre Dame. “I really do think the administration would be very surprised at how responsible we are,“ he concluded. “[W]e might even quiet down here.”Hesburgh defends parietals, writes to student protestors

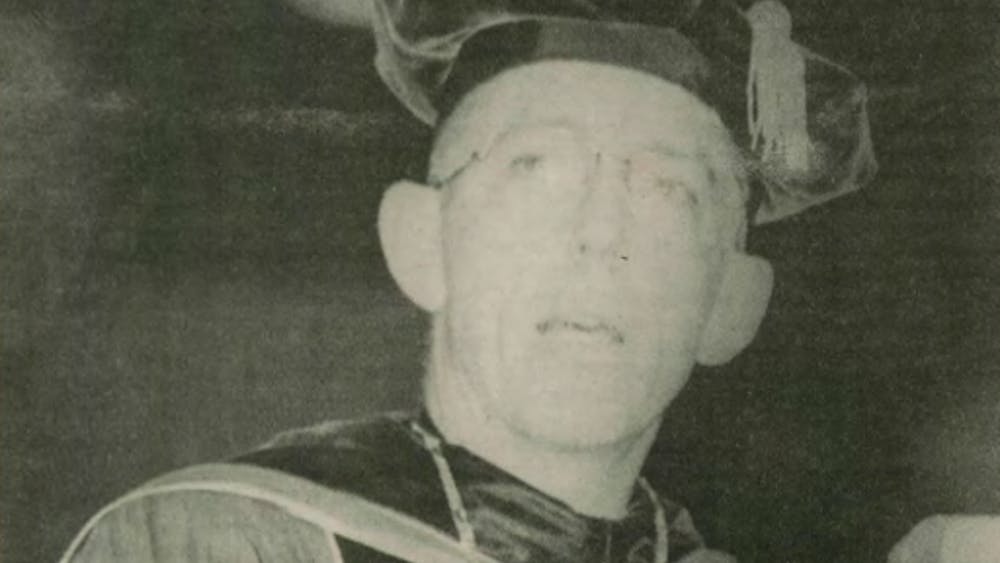

February 19, 1979 | Father Hesburgh | Researched by Maggie Clark

As the student body’s push for the abolition of parietals came to a head — over a third of campus’ 22 residence halls voting to abolish parietals and a student survey revealing the overwhelming popularity of parietals reform among students — Father Hesburgh emerged as a staunch defender of the status quo. According to news editor Ann Gales (’80), he rejected the Campus Life Council’s proposal to abolish parietals on the grounds of maintaining Notre Dame tradition and encouraging the observance of rules.

“The present system of parietals is very much a part of what this University stands for: standards that are higher than most universities, but which can create an atmosphere conducive to education and growth,” Hesburgh wrote.

He then elaborated and noted the benefits of the parietals system — in particular, he claimed the current set of rules promoted privacy, quiet and the comfort of all residents.

Hesburgh also acknowledged Rueter’s point of Du Lac violations being inevitable, but ultimately argued that parietals were necessary in order to prevent unfavorable living conditions. “I am not naive enough to imagine that there is no hanky-panky here,” he wrote. “If people really want to get into trouble, they will find a way of doing so, whatever the rules. However, it is not a permanent living condition here. Bad situations, when they come to light, are judicable according to a single standard.”Hesburgh knew amid the strife on campus, his ruling would not be well received among students.

“I do not expect this to be a popular decision,” he wrote, “but right decisions, those that uphold standards that give a place and its people character, rarely are.”

Finally, Hesburgh spoke candidly to the students protesting parietals, commending their capacity for standing up and voicing their opinions — but somewhere along the line, he admitted, a unilateral decision must be made. “No one is or should be bashful about voicing an opinion,” he wrote. “However, the buck must stop somewhere. Those who have the responsibility for the ultimate decision and the common good must take the heat or get out of the kitchen.” Despite his ostensibly unpopular views concerning parietals, Hesburgh has come to be considered a legendary figure among the Notre Dame Dame community — but in the court of public opinion, parietals haven’t been as lucky. While the student body’s thoughts on the subject remain mixed, history will most likely continue to repeat itself, and calls for reform and abolition will most likely continue. And as the University enters yet another period of restricted visitation policies — many of which have been met with criticism from students — one can’t help but wonder if the Notre Dame student body might emerge from the pandemic with a new perspective on parietals — and, perhaps, a new propensity for protest.