On Monday evening, one DeBartolo lecture hall was filled with the voices of Notre Dame student government’s famous firsts.

Among them, a certain trio marked a steady progression of representation for the group’s highest office: David Krashna ’71, the first Black student body president, Brooke Norton Lais ’02, the first female student body president and Bryan Ricketts ’16, the first openly gay student body president.

Joining them were Elizabeth Shappell Lattanner ’07, the third female student body president and first student assistant to the Gender Relations Center following its founding; former student body vice president and president Becca Blais ’18 and former student body president Alex Coccia ’14.

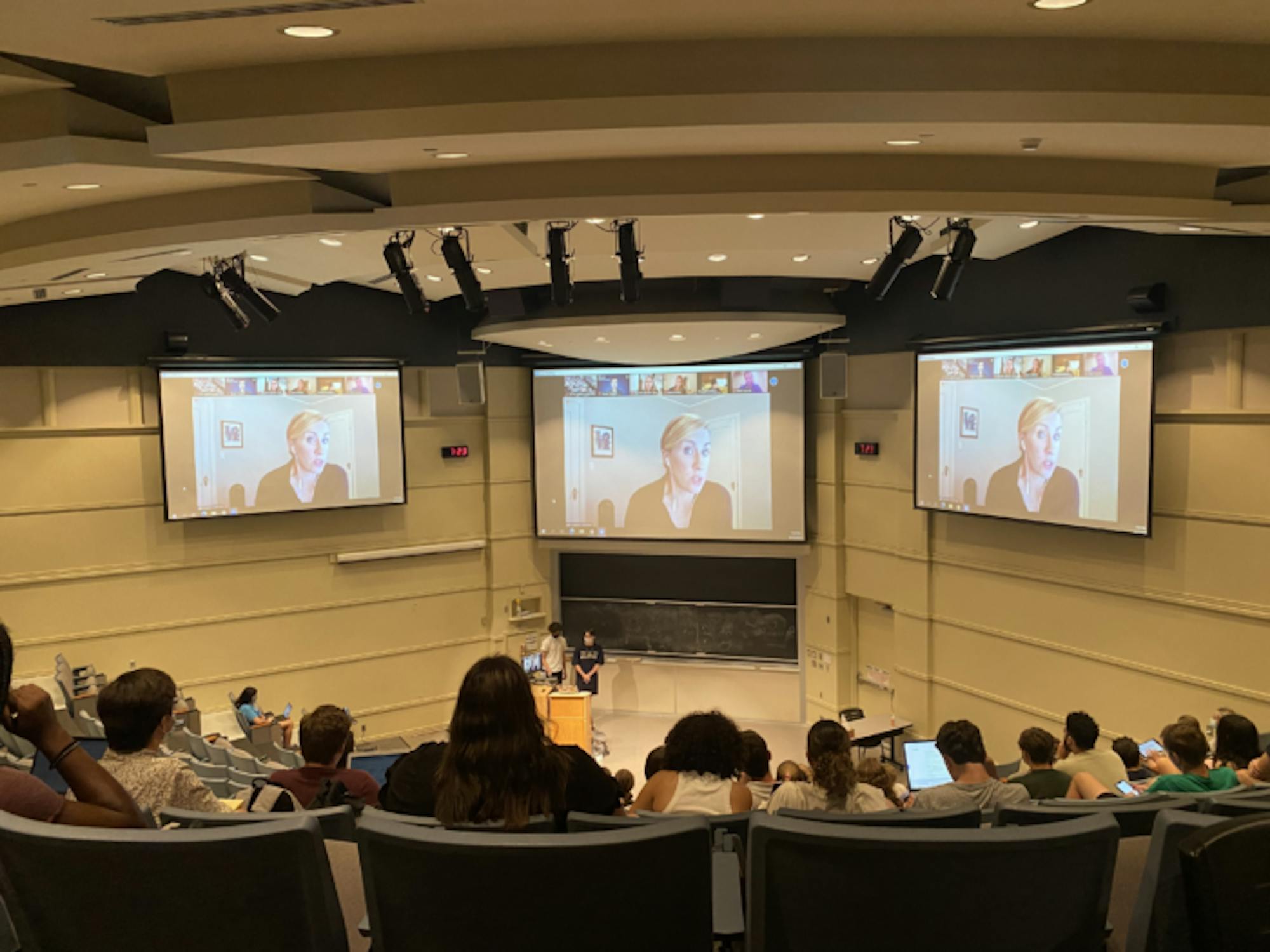

The six University alumni spoke to students as part of a panel on student activism and changemaking within student organizations. Hosted by student government’s University policy core team, the discussion was driven by questions from attending students while panelists participated over Zoom.

Director of University Policy Dane Sherman led the conversation, starting with introductions before transitioning into a Q&A format. To begin, sophomore Layton Hall briefly discussed the emails sent to students detailing recent reported incidents of sexual battery and rape on campus before asking the panelists their thoughts on policies to prevent future occurrences.

In response, Lais argued that while there is still much work to be done in regards to sexual assault prevention methods, the current system represents a vast improvement over those of the past.

“I would say: Thank God you’re getting emails, as sad and terrible as they are,” Lais said. “This would have all been secret and quiet, even when I was there. There was no whisper from ResLife or anyone else about any of this stuff. As shocked as I am to hear that all this is happening, I’m at least slightly gratified to hear that there’s some openness to it — at least to some extent — and that the students are able to speak about it and band together and help make things better.”

And recalling a particular experience during her sophomore year when the University refused to release to students her committee’s detailed report of sexual assault cases on campus, Lais described the actions she took afterward that allowed her to still spark change.

“When they refused to publish that report, we made it the centerpiece of our campaign,” she said. “And so that’s how I think you can make a big impact on things like sexual assault at Notre Dame: You can push through the back channels. There are lots of committees … that are already focused on it. And I think generally, people are trying to do a really good job on it.”

The next question came from sophomore Briana Chappell: “What have you learned since leaving college about changemaking that you think can be applicable to our work in student government right now?”

Drawing from his experience in national politics, Coccia stressed the importance of preparation and research.

“I worked at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services after graduation, and I had to know the institutional memory because a lot of the civil servants had been there for a very long time,” he said. “They were working with political leaders, and in order for them to have good rapport and work well … they had to do their research and they had to go into those meetings prepared.”

Any group fighting for change — whether in D.C. or in DeBartolo Hall — can learn a crucial lesson from these anecdotes, Coccia said: “Know your history, and know your people.”

Answering the same question, Lattanner said that after 11 years on Capitol Hill, she learned how to harness the power of coalition-building.

“An initiative can fly or fail depending on the PR you built around it and whether or not students are bought into the process,” she said. “So it’s important to build coalitions within the student body for a certain thing you’re working on — perhaps certain clubs, certain areas on campus — and thinking creatively about how you can leverage the power of the student body without trying to convince everyone all the time.”

And thinking beyond the bounds of the University’s campus, Lattanner also spoke of healthy competition with other colleges and universities as a viable strategy for sparking change.

“Certainly, Notre Dame is very proud of its unique position in the world, its Catholic character and all the things that make it special,” she said. “But at the end of the day, it’s an institution that has to compete for the best and brightest in our country. So if our peers are doing something better than us, can we challenge the administration to step up?”

In response to a question from senior Zoë Case about how to remain optimistic as an activist, Krashna spoke of healthy responses to uncompromising adversity — something he became very familiar with during his campaign for a term as Notre Dame’s first Black student body president, as his comments regarding the lack of a “comfortable racial atmosphere” on campus were met with pushback from students and administrators alike.

“The Afro-American society — which I was very proudly a member of — the leadership came to me at one time and said ‘David, we just don’t like what you’re doing about Black students,’” Krashna said. “And I said ‘Well, I’m going to continue to do it.’”

And this persistence, Krashna noted, created countless opportunities for him and his cabinet.

“We had an open-door policy with Fr. Hesburgh,” he said. “At any time of day, we were able to go see Fr. Hesburgh, and I was able to get him to do certain things like send me and other students around the country to recruit Black students … So there’s a certain persistence that you’re going to have to have as student leaders.”

And following a question about the 2016 election’s effects on University policy, Ricketts and Blais spoke of the aftershocks felt within the student population, as well as the lessons learned from Trump-era national politics within the microcosm of the University’s campus.

Ricketts, who served as student body president at the time of Trump’s election, described his efforts in organizing the student walkout during Pence’s 2017 Commencement speech, advising students to employ anger in politically effective ways.

“We spent the whole year sort of reeling,” he said. “And one of the things that happens when you feel under threat is the sort of fight-or-flight response, and you want to lash out at the person or political party that’s making it happen … And so change [the anger] from this individual, personal sort of response into something that is like: ‘We’re here. This is about solidarity. We’re building something.’”

Ricketts exemplified this process through an anecdote, recalling the efforts of student activists as they spoke to national news outlets about the purpose of the walkout — all in an attempt to “change the message and drive something home.”

And Blais, whose tenure as student body president spanned the first year of the Trump administration, detailed the differences in campus climate following the events of November 2016.

“After the election, it was pretty shocking for a lot of students,” she said. “There were several hate crimes that started happening on campus. There was a lot of really awful language and actions thrown around, throughout the dorms especially. And I can remember in particular: I lived in Farley Hall, and you would just hear walking around at night chanting. It was just disturbing and strange.”

Faced with a politically charged and heavily divided campus climate, Blais said her political priorities quickly shifted to the immediate needs of students put in vulnerable positions by policy updates, such as changes to Title IX and the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program.

“We had really strong relationships with groups on campus that were already focused on protecting undocumented students,” Blais said. “And we had the opportunity multiple times a week to sit down with those groups and ask: ‘What do you need, and how can we help fill those needs?’”

Answering a final question about dealing with failure and growing from one’s mistakes as a student activist, the panelists reminded students that even the most renowned changemakers make mistakes. In the wake of last summer’s racial reckoning, Lattanner recalled an instance of regret from her time as a student policymaker, as well as a recent story of reconnection.

“I’m really reflecting upon my time at Notre Dame because I don’t think I was — I know I wasn’t — forcefully in favor of a Black Student Union that [a classmate] proposed at the time, and I was blind to the Black student experience,” Lattanner said. “[That classmate] and I connected last summer around the Black Lives Matter protests and had a really great conversation, and he remains a friend to this day.”

But despite the often-unavoidable anxieties of failure and rejection, Lattanner hopes that student government can continue offering students a positive, gratifying experience during their time at Notre Dame.

“This is a new experience for so many of you, so just take a deep breath, enjoy this time and be with the community there,” she said. “Hopefully this is a very enjoyable four years, and a time of growth — as many frustrations and challenges as there are.”