Elizabeth Bruenig couldn’t make it the first time her talk at Notre Dame was scheduled. Alabama death row inmate Kenneth Smith, who Bruenig had known for a number of months and referred to familiarly as “Kenny,” was scheduled to be executed the day before her lecture — and she was to be a witness.

“I made a commitment to this gentleman to witness his execution. And I couldn't break that commitment,” Bruenig said in the opening of her remarks at the Eck Center Auditorium Friday afternoon. “So I had to break this one.”

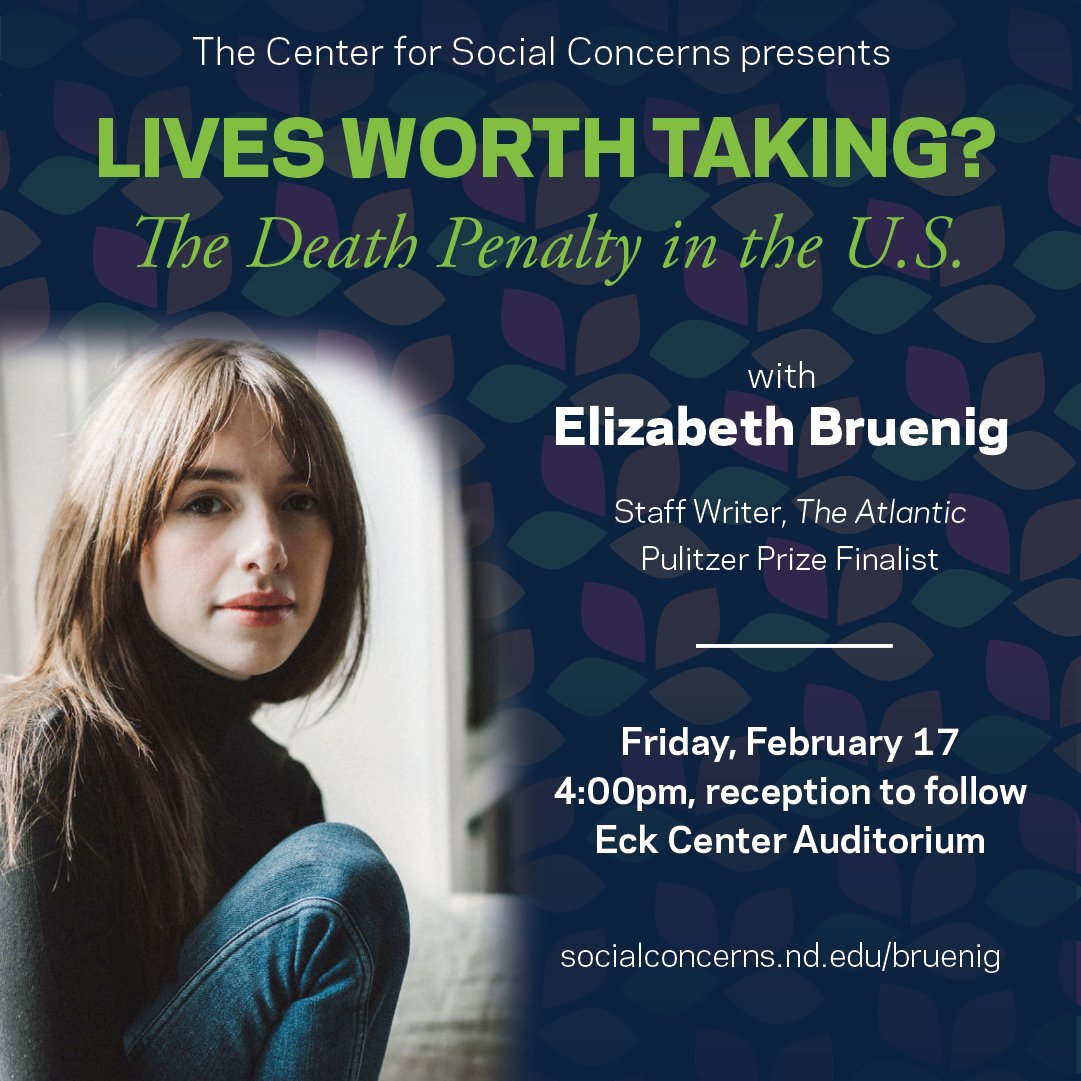

Bruenig — a prominent voice on the Catholic left and an opinion writer with perches at outlets including The Washington Post, The New York Times and most recently, The Atlantic — was named a Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2019.

“Liz writes about a lot of things,” law school professor Rick Garnett said in his introduction to Bruenig. “Theology and politics, sure, but a lot more, including ‘dangerous liaisons at Yale Law School’ and the mystery illness that felled mid-Atlantic songbirds just as COVID-19 looked as though it might relent.”

In a Nov. 2022 piece for The Atlantic describing Smith’s botched execution, Bruenig reported on the experience.

“There was little he could do to stop it, though his attorneys fought tirelessly against dismal odds to avert it, and his family prayed unceasingly for God to save him from what two other men had already endured,” she wrote of the moments leading up to Smith’s impending execution, more than 30 years after his confession to murder-for-hire.

Though the state of Alabama attempted to end Smith’s life on that day, he is still alive on death row.

“What providence did hold for Smith was a severe and bracing mercy: After two days of back-and-forth among three of the nation’s courts concerning his Eighth Amendment rights and the potential of his impending execution to violate them, Smith was strapped down to a gurney for hours and tortured until his executioners simply gave up on killing him,” she wrote.

In a forty-minute talk sponsored by the Center for Social Concernsdelivered to an audience packed to the brim — many stood hugging the walls or doors for lack of seats — Bruenig touched on the moral and spiritual dimensions of the debate surrounding the death penalty.

“We actually make a point to try to get a hold of the most competent, most aware, most healthy people for execution. Their humanity is not a barrier — it’s sort of the point — we want to destroy it. These are lives worth taking,” she said.

Bruenig said that arguments about how incarceration is so brutal that the death penalty might be preferable to convicts — or about the worthlessness of murderers who can no longer provide anything by living — miss key points: both that those sentenced to death almost entirely do not want to die, and that prisoners change during their incarceration.

“One thing to understand about the men and women of death row is that every one of them has a doppelganger, and I don't mean an alternate personality responsible for their crimes. What I'm referring to is just an effect of incarceration over a long period of time. For any given inmate, there exists a version of them captured in news coverage and police records and court papers, frozen in the era of their wrongdoing. And utterly defined by it,” Bruenig said.

“But meanwhile, due to the length of most capital sentences — more than half of the people currently sentenced to death in the United States have currently been on death row more than 18 years — the prisoner himself can't help but change,” she added.

Bruenig also described how age has shaped the prisoners since the crimes that led to their incarceration.

“Plotting aggregate rates of crime against age reveals that there is a sharp increase in criminal activity in mid adolescence, followed by an equally sharp decline in these rates in early adulthood. People appear, in other words, to be most likely to offend as youths and young adults and less likely to offend as mature adults,” she said.

“Thanks to this sometimes decades-long gap between conviction and execution, I often meet prisoners on death row long after this change and many important changes have taken place. Right, I meet them after criminal menopause. These are not the guys who they were when they committed their crimes,” she added.

Bruenig delved into the small minority of death row volunteers, who choose execution over a life sentence, one of which Bruenig witnessed in Mississippi in 2021.

“Oftentimes, the language of trauma is used to describe prisoners' emotional experiences after their crimes, and studies have documented symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in men convicted of homicide, but this is also the realm of the soul. Occasionally the burden is too much, and the spiritual change that is affected is in a sense, total collapse,” she said.

Bruenig described the experience of serving as witness to an execution, being driven from a casino in a white van. At the casino, Bruenig waited with Smith’s lawyer and his family.

“So we're just waiting on the state to call us, and I'm thinking I'm gonna have to really pull it together and be professional for Kenny’s family. I've done this many times before, they haven't. I know what to expect, they don't. I need to be able to interface with the prison staff who can really be bullies to the family, who they also treat like criminals,” she said.

“But at the same time, I was praying very fervently. I don't know if anyone else feels like this, but I feel like when I'm praying in this kind of situation, like kind of a delinquent kid who's got a big favor,” Bruenig recalled.

“And we waited on the call, and it never came. And I have never had this happen to me and the entire time I've been reporting on executions. I have never heard of this happening. But the prison never even came and got us. We were never even put into prison grounds. No call, not even taken into that room. They just let Kenny go,” she said.

The execution was attempted, but ultimately botched.

“They tried to execute him for several hours. They tried to get access to his veins and they failed; they could not access his veins. They tried his hands, his arms, his feet. They took a heavy game surgical needle and put it under his collarbone. Trying to access the subclavian vein here under your neck. They missed. They missed every time,” she recalled.

“I don't know why that is. It's a very strange mistake for them to make.”

In an interview with The Observer after the talk, Bruenig discussed balancing her own emotional and spiritual experience with her professional obligations as a journalist.

“I'm praying internally. I'm going through all this stuff emotionally, but you know, what the families need for me and what the guys need from me is to be a professional,” she said.

“So I'm also always taking notes, I'm recording. Last time I went to Alabama, I was handwriting notes the entire time. I was with the attorney and also asking the attorney for emailed copies of Supreme Court decisions and appeals and stays in real time. So anytime he would get an email [notification], I'd be like, ‘Can I have that? Can I have that notification? Can you just forward me that stays?’ Because I knew, ‘I'm gonna need to document this and its timestamp in my story.’ So I'm always covering ground for the story,” Bruenig said.

“But internally, you have this vast freedom to go to pieces. And I cried in the shower that night. I mean, I just sat down and cried. But you know, that's after my obligations.”

She closed her talk with the implications of these moral and human challenges — and about theories of apology and reconciliation.

“To me — much like the idea of reconciliation depends upon everyday apologies to stay alive — so too does the idea of forgiveness depend on the possibility of change. And change depends on the possibility of tomorrow. The lives of people on death row are unique, but not uniquely fit for destruction, in my view. They're in need of reconciliation and in need of forgiveness. We ourselves are too,” Bruenig concluded.