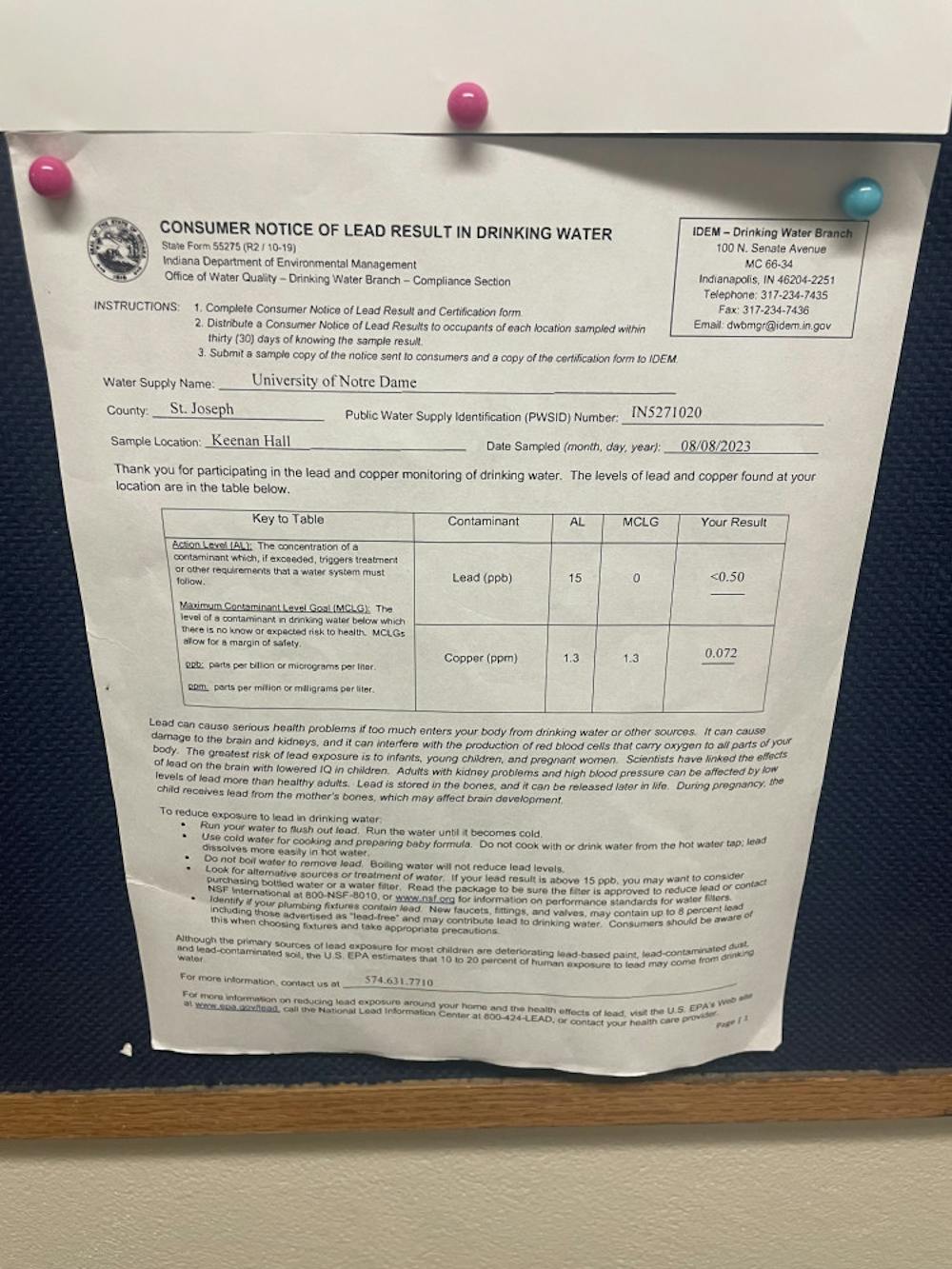

In mid-September, the Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) posted a series of consumer notices on lead concentration across Notre Dame undergraduate residence halls and other academic facilities.

The notices were a product of 43 samples taken in two rounds of testing by Facilities Designs and Operations (FDO) in the Office of the Executive Vice President, which is responsible for monitoring the quality of drinking water on campus.

In the first round of testing conducted Aug. 8, three of the 20 locations recorded lead levels above the actionable level as established by the 1996 Clean Water Act. The act specifies that the concentration of lead within a water system should not exceed 15 parts per billion (ppb).

The three locations — Cavanaugh, Farley and Zahm Halls — all tested above this level. In one of these locations, the max exceedance was measured at 28 ppb, nearly double the actionable amount.

However, according to Michael Cira, a senior environmental and safety specialist within FDO, a procedural mistake can explain the test results.

“It was quickly evident that the samples had been collected prior to the annual water main flushing project, resulting in water that may have been sitting in some of the mains for months due to the building not being in use over the summer break,” Cira said. “[This was] not consistent with our standard operating procedure of testing after the flushing.”

Following the initial testing, the campus water system was flushed and additional samples were taken by the University. The Aug. 8 tests were also reported to IDEM, which said the water system at that time had indeed exceeded the FDA standard for lead in a Sept. 14 letter.

Shelley Love, senior environmental manager of the drinking water branch on copper and lead levels at IDEM, offered an explanation for the events.

“Notre Dame did not flush the lines at this location due to an operator error which has been addressed,” Love said. “The operator doing the sampling is being trained on the proper procedure for testing in the future.”

Following the single sample exceedance, Notre Dame conducted more testing, Love added.

“The University conducted several additional samples at that location and the results came back well below the current Clean Water Act acceptable levels,” she said.

Both Love and Cira emphasized that the initial exceedance, the flushing of the system and the second round of testing were all completed before students arrived on campus.

The day after FDO was officially notified by IDEM of lead exceedance, a follow-up letter indicated that “based on the additional lead and copper samples collected by the University of Notre Dame for the June 1 through Sept. 30, 2023, monitoring period, your system has not exceeded the lead action level.”

The Sept. 15 letter also included that the 90th percentile of the 43 samples conducted over the period was 7.54 ppb.

Although this is below actionable levels, it is still above the FDA’s Maximum Contaminant Level Goal (MCLG), which is the highest level of a contaminant within a system at which no known or expected health risk is present. The MCLG for lead concentration is zero.

In the event that lead levels are consistently higher than 15 ppb, one requirement from the Clean Water Act is to post educational materials pertaining to healthy practices for avoiding lead consumption. One such material was drafted for Notre Dame after their initial testing.

The information bulletin lists some of these practices as letting roughly a gallon of water drain from any faucet used for cooking or drinking that has gone unused for more than six hours and warming cold water on the stove rather than using hot tap water which can dissolve lead at higher levels.