In 1991, when many current seniors were born, undergraduate tuition at Notre Dame cost $13,505. Each year since, Notre Dame has expanded, and so has its price tag.

In a Feb. 18 press release, University President Fr. John Jenkins announced that undergraduate tuition at Notre Dame would increase by 3.8 percent for the 2014-15 school year, bringing the total to $46,237. After room and board, that total is $59,461.

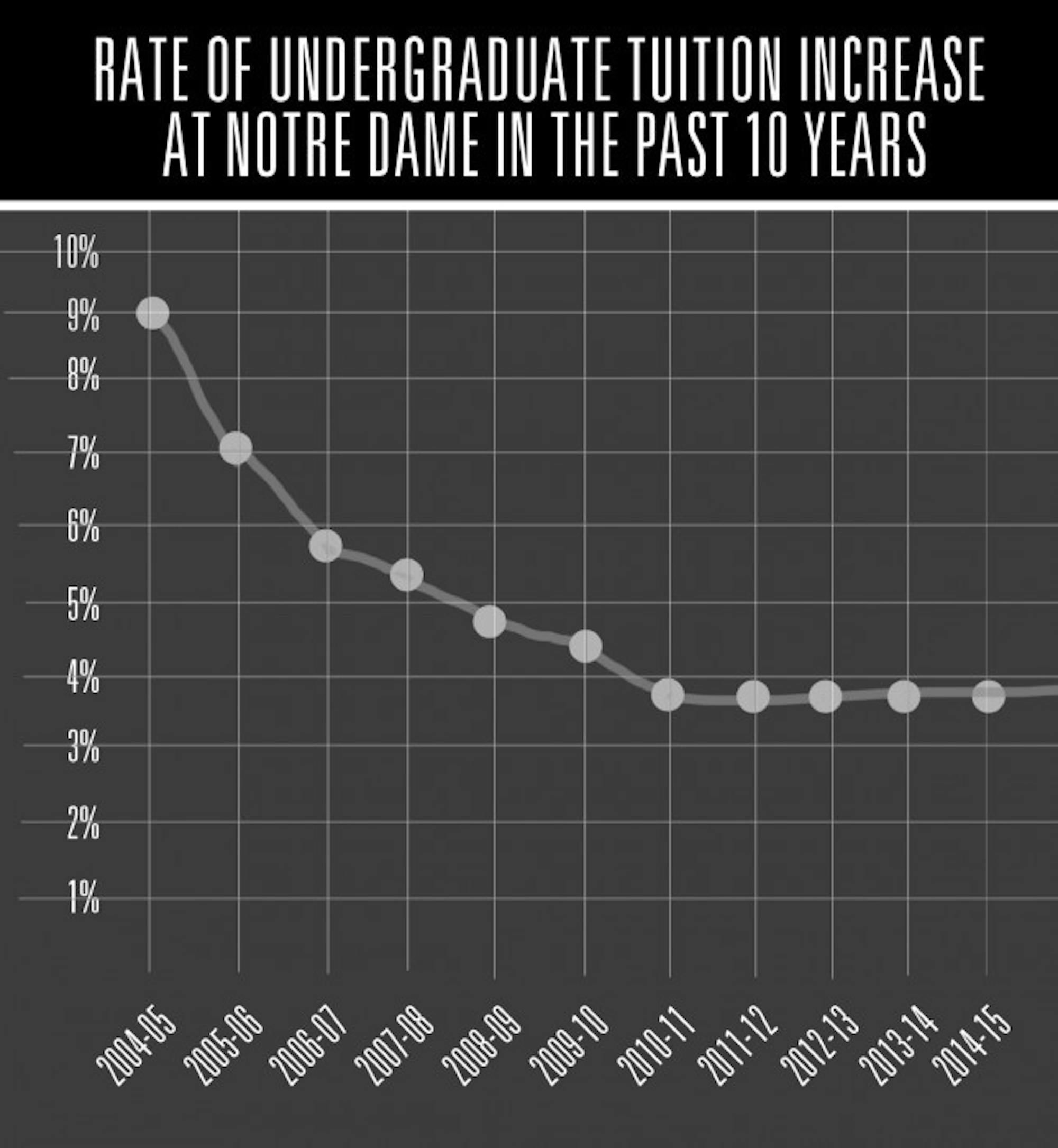

The increase itself is routine. According to a chart provided by University Spokesman Dennis Brown, this marks the fifth year in a row in which the change is limited to 3.8 percent, compared to increases recorded as high as 9 percent in the past 10 years.

Steph Wulz

Vice President for Finance John Sejdinaj said the process of setting tuition for each year is just one dimension of the University’s annual budget plans, which are approved by the Board of Trustees. Jenkins, University Provost Thomas Burish and Executive Vice President John Affleck-Graves set goals for the year ahead before beginning the budget creation process, Sejdinaj said.

“We have tried to get guidelines in place about how we want to think about tuition … and other aspects of the budget,” Sejdinaj said. “It’s really tuition, financial aid, salaries [and] benefits that are the big drivers. And once we’ve done all those, we see what money is left for other priorities.”

Sejdinaj said the budget committee takes into account the cost of similar “peer institutions” when determining tuition guidelines.

“We don’t want to be too high, and we don’t want to be too low versus our peer groups,” he said. “So we’re always watching what our peers are doing and where we’re at.

“In the last four years, we’ve been able to look at what we actually need to fund the needs of the University, and we’ve been able to keep it down.”

Specific factors that affect the percent increase each year include compensation and benefits for all employees, “non-salary” components, such as utility costs or information technology services, and building and operational costs of new facilities, according to Sejdinaj. The expenses associated with these dimensions depend largely on inflation or other factors outside the University’s control.

One behind-the-scenes group that works to streamline expenses is the Office of Continuous Improvement, which Sejdinaj said works across campus to control costs.

“They look at how we can [streamline] our work flows and our processes to try to save people time, so we don’t have to hire additional employees and we can save hours just by adjusting how we do these processes,” he said. “We have the Office of Sustainability that works with buildings like the power plant … to save on our utility costs.

“There are a lot of things at work. Yes, we’re doing tuition increases, but we’re also doing these other things and trying to hold down the costs.”

Sejdinaj said in recent years, the budget committee has prioritized investment in financial aid. Available aid has increased at a higher rate than tuition costs, he said.

“In fiscal year 2000, we were spending about 28 million on financial aid, and next year we are budgeting 120 million,” he said. “So tuition is going up, but the increase in financial aid is growing three times what tuition is growing.”

Notre Dame’s financial aid endowment is relatively high compared to peer universities, and more than 60 percent of financial aid comes from this endowment, which is close to $1.5 billion. Having this money allotted for financial aid “takes a lot of pressure off tuition increase so the tuition can be used for bigger projects,” he said.

“Financial aid will still continue to be a priority because we’d like to get that 60 percent up closer to 80 percent, so that even more [money] is coming from scholarship endowment and that puts less pressure on tuition,” he said. “From a University standpoint, we’ve got to work to keep tuition low, and we’ve got to work to increase financial aid.”

Sejdinaj said the goal is “not to have anyone graduate with more than 10 percent of the cost of four years here in need-based loans.” It is impossible to determine exactly what is or is not funded specifically by tuition because that money is just one stream into the larger “pot” of the overall budget, he said.

“It’s hard to divide the pots, because there’s tuition but we also budget the net income from our auxiliaries, so athletics, the various food services and so on,” he said. “It [goes into] one big pot of money, and then we divide it out.”

The bottom line when approaching the budget model is to think about it in both percentages and actual dollar amounts, Sejdinaj said.

“When we look at the budget model, we take the last five years or so and say ‘Okay, where are all the revenue sources? Well, if we increase tuition by this, and salaries go up by this, and inflation goes up by this and so on, how do we make a balance?’” he said. “You do a little back and forth … and you look at it as percentages to see what’s going to happen, and then you look at it in dollars, too, to see what the actual tuition is then.

“It’s a matter of balance and looking at it from different perspectives.”