With the lights shining down Saturday night inside an overflowing Notre Dame Stadium, the Irish will align on the west sideline, the Wolverines on the east strip. One-hundred and sixty feet of crisp FieldTurf will separate Notre Dame and Michigan.

But the two schools are inextricably linked — somewhere along the 150-mile stretch of Midwest roads from Michigan Stadium in Ann Arbor to Notre Dame Stadium in South Bend.

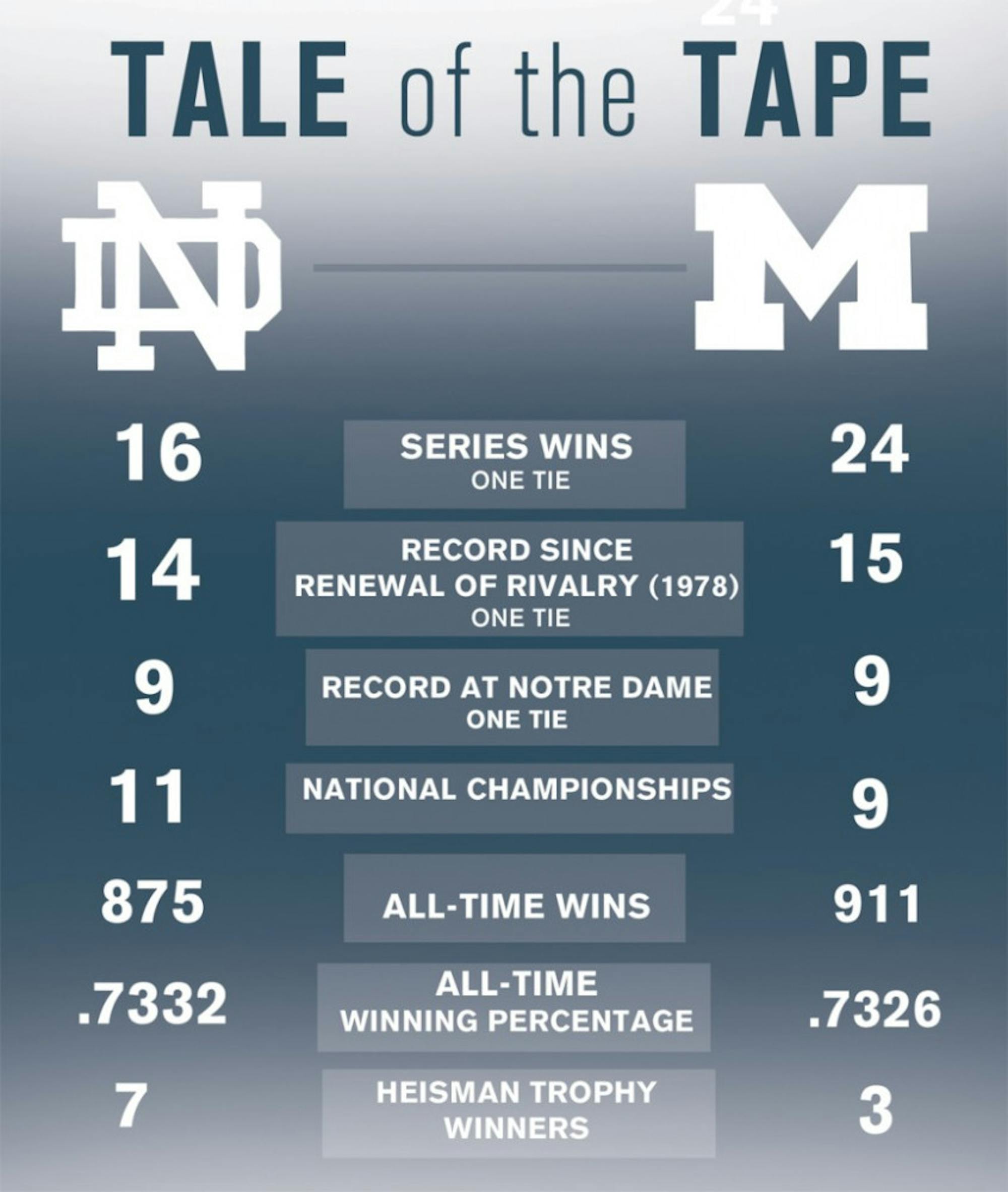

Just six ten-thousandths separate the programs in all-time winning percentage for the best mark in NCAA history.

Both schools feature blue and a yellow-based second color in their logos and uniforms, a rivalry typified somewhere between maize and gold, with the color-wheel balance seemingly swinging each year.

Two teams so close.

But when the Stadium rocks and the whistle blares around 7:42 p.m., Notre Dame and Michigan will collide for the final scheduled time.

Until they meet again.

The Beginnings

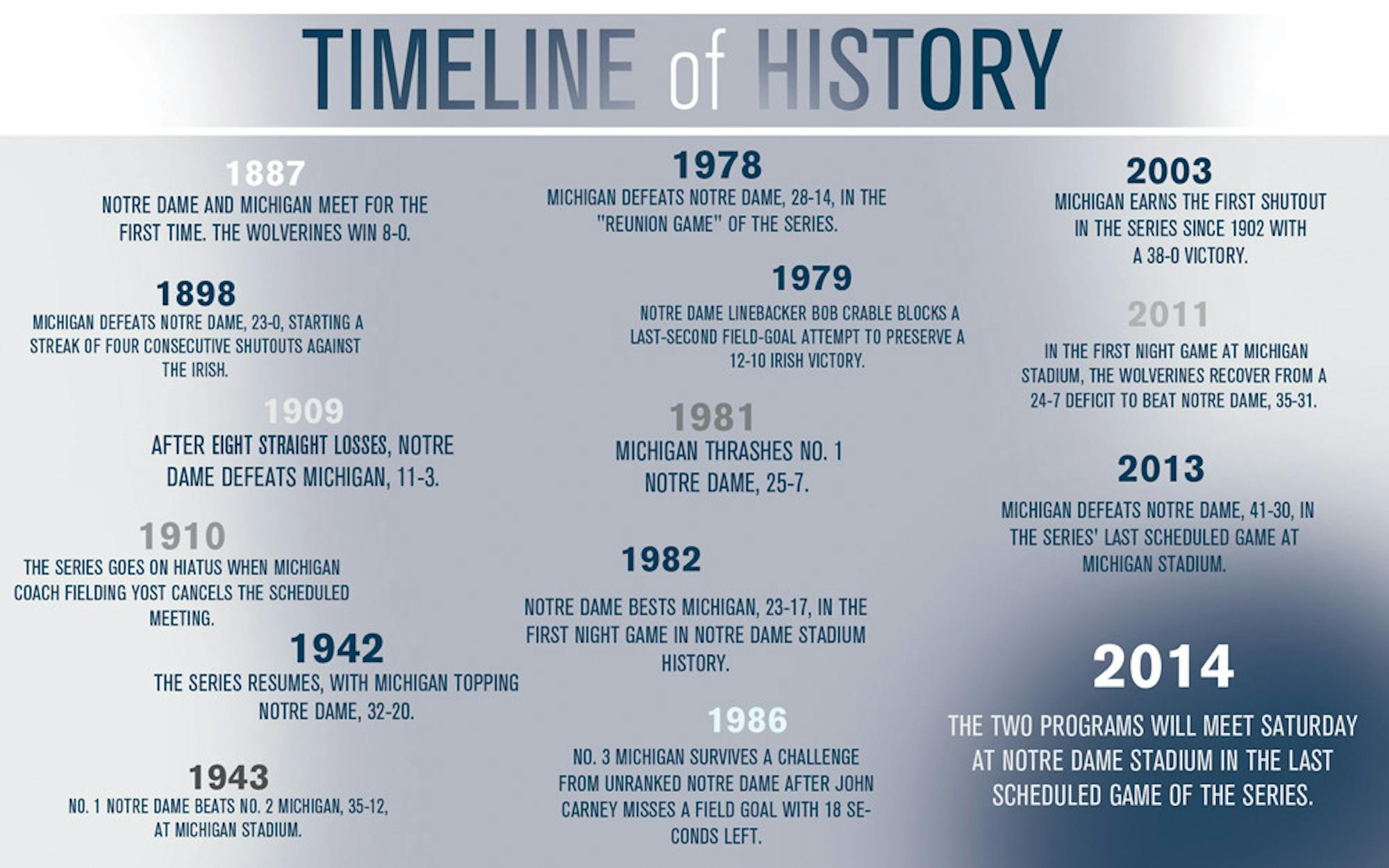

Notre Dame and Michigan are meeting for the 42nd time, making the series just the eighth-longest in Irish history.

But Notre Dame’s history with Michigan dates all the way back to 1887, when the Wolverines topped the yet-to-be-named Irish, 8-0, in South Bend in something that was more tutorial than full-fledged contest, according to football historian John Kryk.

“Michigan literally taught Notre Dame how to play in 1887,” said Kryk, who wrote “Natural Enemies: The Notre Dame-Michigan Football Feud.” “A couple of former Notre Dame students had gone off to Michigan, and they were keeping in touch with buddies at Notre Dame, especially with sports-minded Brother Paul, and they arranged that first game.”

From there, Kryk said, Notre Dame ramped up its desire to play this new game, one that would eventually become a key component of the institution. But the teams were at completely different junctures, with Michigan already a Midwest power, Notre Dame not yet even its fledgling punching bag.

“They suddenly wanted to be what Michigan was, a power at that time,” said Kryk, who is a national NFL columnist for the Toronto Sun.

The eager Irish met with the Wolverines six times over the next five years after their inaugural clash in 1887. Not once did Notre Dame win. Michigan outscored its local foe by a combined score of 121-16 through the first eight meetings.

But in 1909, Notre Dame claimed an 11-3 victory, earning the first of its 16 wins in the series. The two teams, however, would not meet again until 1942.

Kryk said that, for Michigan, there was no glory in playing Notre Dame at that point. Michigan and its conference partners essentially decided to “blow Notre Dame off the course” by not playing them, Kryk said.

Stuck in northern Indiana and craving football, Notre Dame had to venture outside the Midwest to fill its schedule.

“That’s why Notre Dame became the national school because they had to go outside the Midwest in the teens and then in the early 20s of [former Irish coach Knute] Rockne to find anyone worth playing,” Kryk said. “And it was because Michigan and their Big Ten partners were snubbing them.”

Notre Dame rose to national prominence in the 1920s under Rockne — without Michigan and its conference cohorts. But the Irish still made one last-gasp effort at joining its regional counterparts, making an unsuccessful last push in 1926, according to Kryk.

“That’s when Notre Dame went, ‘Alright then, we’re going to be an independent. We’re going to embrace it,’” Kryk said.

Feuding Over Football

Following Notre Dame’s victory in 1909 and before the renewal in 1978, the two teams met just twice — in 1942 and 1943.

Feuds between Rockne and Fielding Yost, Frank Leahy and Fritz Crisler extended the hiatus until Don Canham headed the Michigan athletic department in 1968.

Michigan’s attendance at football games was dwindling — relatively speaking, of course — according to Kryk, to about 65,000 for games against teams not named Michigan State and Ohio State. After lying dormant since 1943, talks between Notre Dame and Michigan started up again in the late 1960s.

Notre Dame athletic director Edward “Moose” Krause and Canham, looking for a way to fill his university’s then-101,000-seat stadium, agreed in January 1969 to a four-game series that would begin in September 1978.

A Rivalry Resumed

The two programs reconvened their series at Notre Dame Stadium on Sept. 23, 1978 in a matchup between the No. 5 Wolverines and No. 14 Irish, the defending national champions. With quarterback Joe Montana at the helm, Notre Dame jumped to a 14-7 halftime lead, but Michigan added three unanswered touchdowns in the second half to cruise to a 28-14 victory.

While it wasn’t as close as many matchups in series history, the atmosphere surrounding the 1978 matchup, known as the “Reunion Game,” showed that the rivalry was back, former Notre Dame kicker Chuck Male said.

“It was pandemonium; the fans were going crazy,” he said. “It was just really exciting to be part of that, and it was really exciting for college football to have that rivalry reignited.”

The following September, Notre Dame and Michigan met at Michigan Stadium for the first time since 1943. As in the year before, the Irish entered the game, their season opener, as the underdog.

Male ended up providing all the scoring for an Irish offense that was in the process of replacing Montana. The walk-on booted four field goals to give Notre Dame a 12-10 lead. Still, Male’s efforts would have been for naught if not for a block by Irish linebacker Bob Crable on Michigan kicker Bryan Virgil’s last-second, game-winning field goal attempt.

Crable’s field-goal block didn’t come in the traditional form, however, as he made the block by leaping on the back of Michigan center Mike Trgovac and stopping the ball with his hip.

“Literally when [Trgovac] snapped the ball, his two hands went on the ground, so [he] acted as a step, and as the guards leaned in to take care of what was coming over the top, they pushed me up as well,” Crable said. “… [The ball] hit me in the hip, and the worst part of it became the landing. When I was up there, the ball hit, and I was projected out. … My feet were on the center, but my body was out in front, and I came down right on my head. Luckily, I didn’t break my neck.”

Although Notre Dame and Michigan hadn’t played for a few decades preceding the “Reunion game,” Male said the Irish players of the late 1970s recognized the Wolverines as a top rival.

“When you looked at the schedule, it was one of our target games, the Michigan game,” he said.

The intensity of the Michigan series was further fueled by the geographic closeness of both teams, Male said.

“You had a situation where we didn’t even fly, took a bus to the game, it was that close,” he said. “You mixed in a fanbase with lots of fans that were loyal and liked both teams because of the geographic proximity, and it really made for an interesting rivalry.”

While the atmosphere surrounding the resumption of the Notre Dame-Michigan series was lively on both sides, the scene at Michigan Stadium provided some unique challenges for the Irish, Crable said.

“Wherever you go, you’ve got those situations where you’ve got the crowds, you’ve got obnoxious people, you’ve got drunk people, you’ve got all different characters that exist in the stadium,” he said. “But at Michigan, it seems like it was exaggerated — everything was exaggerated.”

The Holtz Years

Lou Holtz took over the Notre Dame program in 1986 and steered the Irish for 11 seasons, the first nine of which featured dates with Michigan.

Both teams were ranked in eight of the matchups. On five occasions, both teams were slotted in the top 10.

“I didn’t think twice about it,” Holtz said by phone this week. “Our schedule was ranked the toughest in the country almost every year I was there. When I went to Notre Dame, [University executive] Father Joyce made this abundantly clear.”

The only year either team was unranked was 1986, when the Irish opened the campaign against the No. 3 Wolverines at Notre Dame Stadium.

“We outplayed them badly,” Holtz said.

Holtz recalled how Michigan quarterback Jim Harbaugh threw a late fade for a touchdown, only for Irish quarterback Steve Beuerlein to bring Notre Dame right back down the field. Inside Michigan territory, Beuerlein rolled to his left and fired to the back of the end zone for tight end Joel Williams. Williams landed close to the back line of the end zone, and the pass was ruled incomplete. Irish kicker John Carney missed a field goal on the last play of the game, and the Wolverines won 24-23.

“That was devastating to lose that game,” Holtz said. “I remember so much about that game. … If they had replay then, we win the game.”

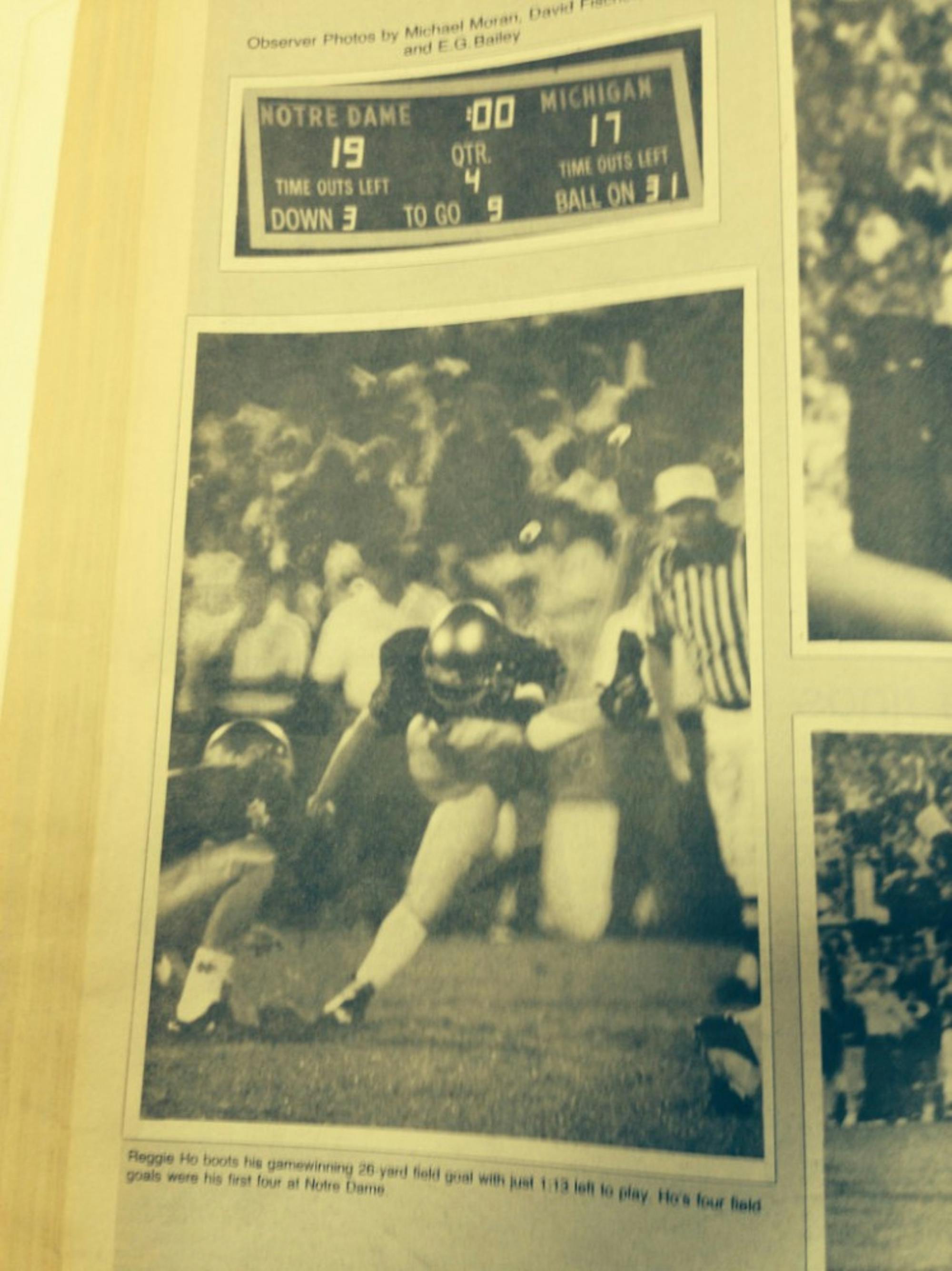

Two years later, back at Notre Dame Stadium, the Irish waltzed into the season as the No. 13 team in the nation set to face the No. 9 Wolverines under the lights — portable lights hauled in for the occasion.

In order to win, Holtz and the Irish had to rely on the unlikeliest of heroes, 5-foot-5 walk-on kicker Reggie Ho. In the opening act of a national championship season — Notre Dame’s last title — Ho drilled four field goals, the last of which split the uprights with 1:19 remaining in regulation and propelled Notre Dame to win No. 1.

“Coach Holtz, he prepared us for a lot of pressure situations,” Ho said this week by phone. “Fortunately, I made the first one. I said whenever I’m called upon again to go out, I’ll try to make the next one.”

The next Michigan-Notre Dame matchup followed in 1989 and pitted the No. 1 Irish against the No. 2 Wolverines. Irish flanker Raghib “Rocket” Ismail blazed back two kickoff returns for touchdowns to top Michigan, 24-19, on its own turf.

“I remember saying to the team, ‘I don’t think they’ll kick it off again to Rocket, but then again they’re arrogant so be alert for either a regular kickoff or a squib kick,’” Holtz recalled. “Gee, he kicked a perfect kick. Rocket caught it all on the run and we went on to win that game.”

When the teams met two years later in Ann Arbor, it was Michigan’s own dynamic receiver and return man, Desmond Howard, with the highlight play. In the fourth quarter, the No. 3 Wolverines clung to a 17-14 advantage. But Michigan faced 4th-and-1.

“Fourth-and-six-inches,” Holtz corrects himself.

The rest is, well, history. Howard snagged the touchdown in the back of the end zone.

“They didn’t have enough confidence to run six inches,” Holtz griped.

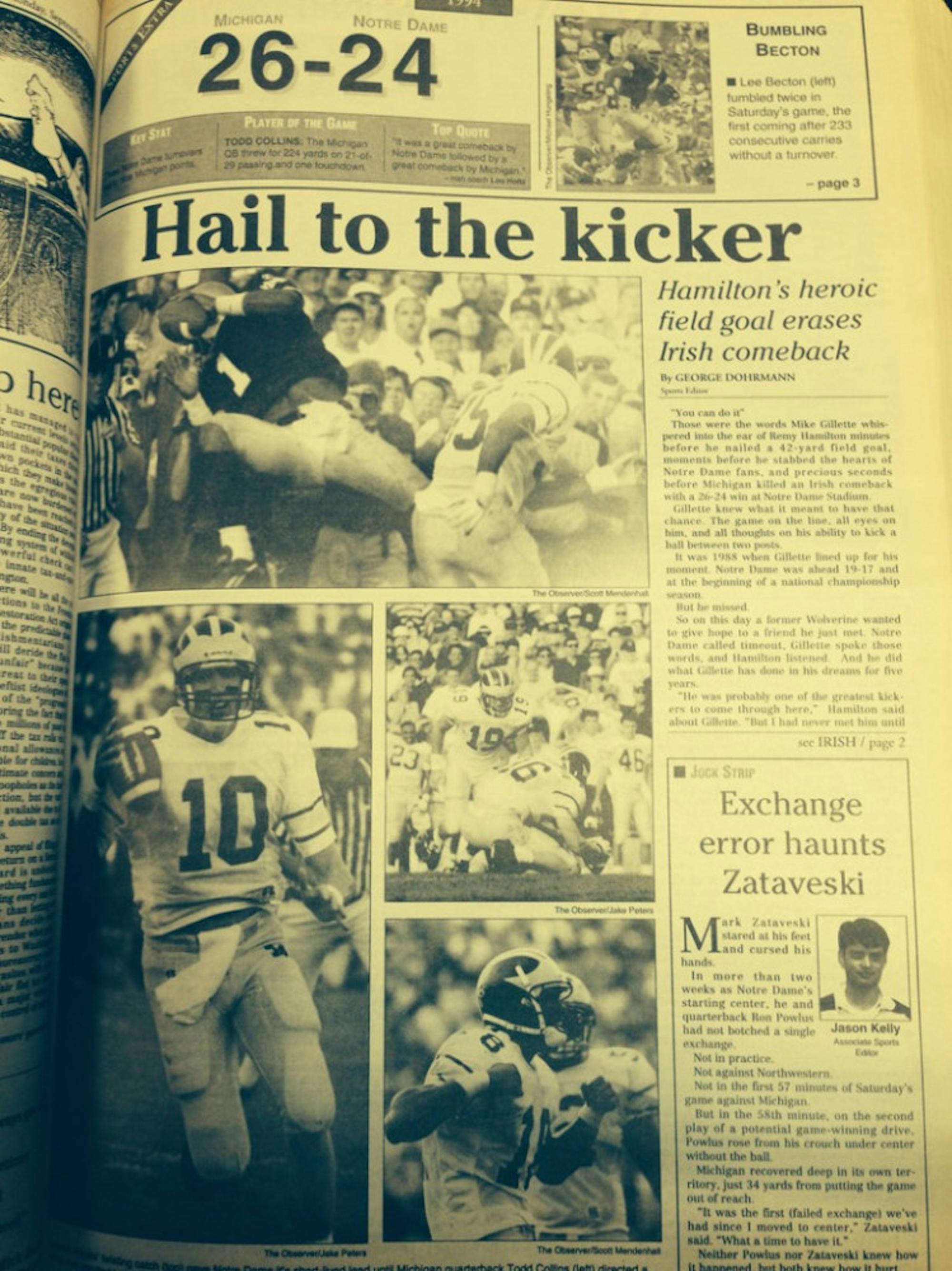

In Holtz’s final game against Michigan in 1994, No. 6 Michigan outlasted No. 3 Notre Dame, 26-24, at Notre Dame Stadium. The matchup also marked then-defensive coordinator and eventual head coach Bob Davie’s first taste of the rivalry.

Notre Dame stormed ahead with a few minutes left in the game, but Wolverines quarterback Todd Collins led Michigan down the field, and kicker Remy Hamilton buried a game-winning field goal.

“I’ll never forget just the momentum in that stadium as we took the lead and then you could hear a pin drop when that kid kicked that long field goal to beat us,” said Davie, who spent eight seasons coaching at Notre Dame.

Holtz, some 20 years removed from his final Michigan-Notre Dame game, had nothing but praise for the rivalry.

“They were always great games,” Holtz said. “I loved [Michigan head coach] Bo Schembechler. And Michigan and Notre Dame were so similar, we recruited the same caliber of people.”

Stacking Up the Rivalries

There’s a duality in the Michigan-Notre Dame rivalry. The teams first met in 1887. But they also have only played 41 times. Still, there’s an impressive power to the rivalry.

“Nationally it was at the time, until the mid-90s … one of the most important college football rivalries,” Kryk said. “And that’s saying something when they hadn’t even played by the late-70s.”

So what is it about this rivalry?

“It’s not the intensity,” Holtz said. “It’s not the hatred that some rivalries have. … [Former Ohio State head coach] Woody Hayes wouldn’t even wear anything that came close to Michigan’s colors. South Carolina-Clemson, Alabama-Auburn. Those are bitter rivalries.”

Michigan-Notre Dame is different, Holtz argues.

“It’s a country that’s going to miss it,” he said. “It’s not necessarily Notre Dame fans. But the country is going to miss it. Because it’s one game that everybody looked forward to every year. You knew it was on the schedule.”

Soon after his five-year stint as Notre Dame’s head coach concluded in 2001, Davie joined ESPN as a college football analyst, allowing him to travel around the country, sampling a smattering of the sport’s best rivalry.

How does Michigan-Notre Dame stack up?

“I think it’s an older rivalry,” Davie said, pausing to explain himself.

“The stadiums were older, and it just reeked of tradition,” said Davie, slowly enunciating each syllable for effect, as if he smells it again.

“Just the smell in Notre Dame Stadium, the grass, the grass of what it smelled like — that may sound corny to some people — but that’s the thing I miss most about Notre Dame, just the oldness of it, how old it all seemed,” Davie said.

Saturday’s game, though, will be the first played on FieldTurf at Notre Dame Stadium, heralding the final chapter of the rivalry’s history — for now, at least.

The Future of the Rivalry

Following Saturday’s tilt, Notre Dame and Michigan don’t have another scheduled game on the docket. A request to speak with Notre Dame Director of Athletics Jack Swarbrick was not returned.

“Everybody knows how big this rivalry is,” Michigan graduate student quarterback Devin Gardner said Monday. “It sucks that it has to go and it’s not appreciated by everybody.”

Notre Dame announced its 2014, 2015 and 2016 schedules in December, debuting the first workings of a five-game ACC commitment, one that has tightened the available permutations for Notre Dame’s schedule.

“We have really limited inventory going forward,” Swarbrick told The Observer in December. “We’ve tried to protect enough inventory so we can still do an SEC team. That’s sort of the priority in the next cycle to see if we can do that.”

“From my point of view, I hate to see it miss like the [rest of the] country, because it was great. It was great to participate in it,” Holtz said. “But, those people know what’s in the best interest of Notre Dame. I accept that. I trust that.”

For now, Saturday is the last scheduled meeting — a stopping point in the back-and-forth battle.

“We’ve had this wonderful series since 1978,” Kryk said. “Almost every game is just a classic, memorable for something.”

For now, there’s one more chapter to be written in the epic.

Managing Editor Brian Hartnett contributed to this story.

To read the rest of our Irish Insider, click here.