Nearly 10,000 members of the Notre Dame community gathered in Purcell Pavilion to remember University President Emeritus Fr. Theodore Hesburgh at a memorial tribute Wednesday.

Twelve invited speakers — including President Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn, former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, and one current and two former U.S. Senators — recounted stories, shared Hesburgh’s words of wisdom and reflected on his legacy.

The tribute was the final event in the series of official memorials and services celebrating the life of Hesburgh, who died last Thursday.

Anne Thompson, a correspondent for NBC News and a member of the Notre Dame Board of Trustees, emceed the program, which included music from campus choirs and musical ensembles.

University President Fr. John Jenkins delivered opening remarks, Holy Cross Provincial Superior Thomas J. O’Hara said a convocation prayer, and Superior General Richard V. Warner ended the evening with a benediction.

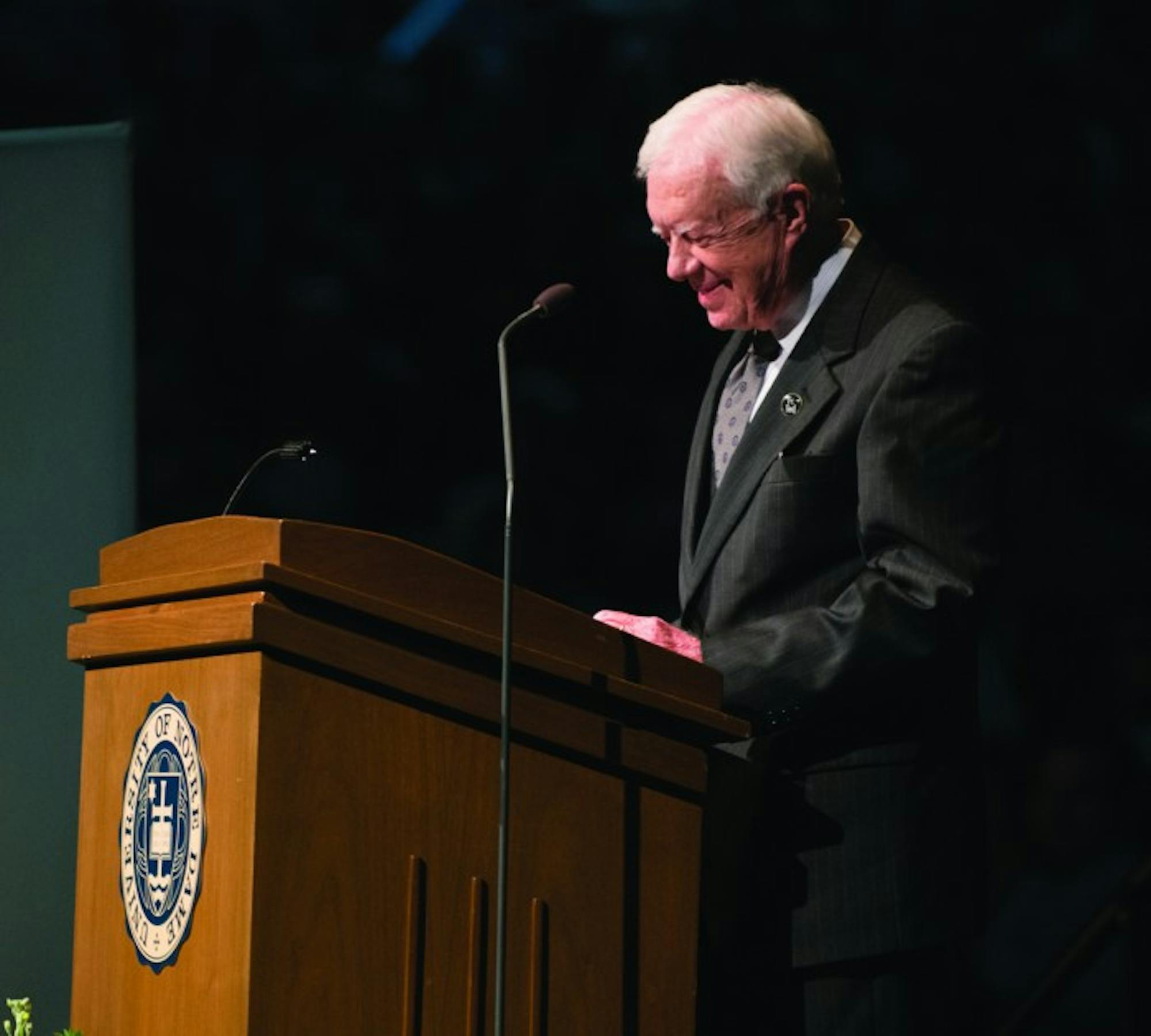

Jimmy Carter, 39th President of the United States

Carter said he first spoke to Hesburgh while he was a presidential candidate and often took Hesburgh’s advice after he was elected.

“Once when I asked him, ‘How can you advise anybody to be a leader of a great nation?’ he said, ‘be human,’” Carter said. “I took that advice as well.”

During his presidency, Carter appointed Hesburgh to be ambassador to the UN Conference of Science and Technology for Development, to a commission to create the Holocaust Museum and to the Select Commssion for Immigration and Refugee Policy Reform

That led Carter to offer Hesburgh a favor in 1979. Hesburgh, an airplane lover, asked for a ride on an SR-71 Blackbird, the fastest plane in the world.

“I said, ‘Fr. Hesburgh, it’s not customary for civilians to ride on a top-secret airplane,’” Carter said. “He said, ‘That’s all right. I thought you were Commander-in-Chief.’”

Carter said he called the Secretary of Defense and then a pilot of a Blackbird, asking him to go faster than the 2,193-mile-per-hour record for the plane.

“On the last day of February 1979, Fr. Hesburgh went up in an SR-71 Blackbird airplane, and he and the pilot went 2,200 miles an hour,” Carter said. “He set a new world record for the fastest any human beings have ever flown, except the astronauts in a rocket.

“We all know that Fr. Hesburgh has an almost indescribable list of achievements in education and human rights and service to others. But in his autobiography, he gives me credit for arranging this fast ride. And he says that was one of the greatest achievements he ever accomplished.

“Well, I’m proud that I was able to do that for him, because he did so much for people everywhere.”

Condoleezza Rice, former U.S. Secretary of State

Rice met Fr. Hesburgh in 1970 when the Civil Rights Commission came to the University of Denver to hold hearings.

“Now, the great civil rights legislation was already done,” Rice said. “But for this little girl, still a teenager, but whose memories were of life in a segregated Birmingham where her parents couldn’t take her to a movie theater or a restaurant, where she had gone segregated schools until she moved to Denver, Colorado. For this girl, Fr. Ted’s clear understanding and belief that America had to be so much better than it was reassuring, and it was inspiring.”

While studying at the University, Rice said Hesburgh frequently interacted with students, always happy to discuss current issues with them.

“Somehow his touch was so personal, that even those who met him once, or maybe never at all, knew him, and they loved him," Rice said. "Just as he loved Notre Dame.”

Rice said she and Hesburgh remained friends after she left Notre Dame and eventually joined the faculty at Stanford University.

“Throughout the years that followed, my life was truly enriched and my spirit was refreshed by that friendship with Fr. Ted,” she said. “As Provost of Stanford, we would sometimes talk about higher education … . But the note that he sent me most proudly was the one that told me that for the first time, Notre Dame’s valedictorian was a woman.”

Eventually, Rice left Stanford to work in the government, serving as both National Security Advisor and Secretary of State. During her time in the latter position, she dedicated an immense amount of time to negotiating peace between Israel and Palestine.

After she returned from one visit to the region, she said, she received a call from Hesburgh, who told her she sounded tired. He suggested she invite the Israeli Prime Minister and the Palestinian Authority President to the University’s cabin in Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin, to talk about peace.

“I would have loved to have done it,” Rice said. “I never quite got them that far. But somehow, I was encouraged and spurred ahead to try. Because Fr. Hesburgh understood that you can never accept the world as it is, you have to work for the world as it should be.”

Rosalynn Carter, former First Lady of the U.S.

Mrs. Carter met Fr. Hesburgh when they served on the national crisis committee formed in response to the Cambodian genocide.

As part of the administration’s initial response to the conflict, Mrs. Carter and several other officials went on an official visit to Cambodian refugee camps. She said she was struck by the immense poverty and suffering she witnessed.

“All the way home I felt this great responsibility for me and Jimmy and the whole country to do something about this tragic situation,” Mrs. Carter said.

When Mrs. Carter returned to the White House, she had a phone call waiting for her, she said.

“And guess who was calling me?” Mrs. Carter said. “Fr. Ted, eager to go to work. Two days later, he was in the White House, having formed a national crisis committee which raised a large fund from private donors to support refugees.

“He was a most effective leader and integral in the committee.”

Later, Hesburgh invited Mrs. Carter to serve on the Advisory Board of the Kellogg Institute for International Studies and to co-chair the DeBurght Conference on religious freedom in Soviet Russia, she said.

The most striking thing Mrs. Carter remembered about Hesburgh was his enduring commitment to human rights for all, she said.

“He continued until his last days to be an optimist who saw the world as he would like it to be, with his help,” Mrs. Carter said.

“Fr. Ted is one of the greatest humanitarians I have ever known, and I am honored to have been and always will be honored to have had a wonderful friendship with him.”

Barack Obama, President of the United States

In a pre-recorded address, Obama described Hesburgh’s work and leadership on the Civil Rights Commission and praised his initiative and desire to do good.

“There’s a story that I love from the early years of that Commission, back when Fr. Ted was a founding member,” Obama said. “As you can imagine, those discussions were often long and difficult because, as he later wrote, the Commission agreed on very little outside of the Constitution.

“So when it came time to write their final report, Fr. Ted had an idea. He took them all to the Notre Dame retreat up in Land O’Lakes, Wisconsin, and there he said, they realized that despite their differences, they were all fishermen. In the literal sense. So they fired up the grill, caught some walleye, and ultimately the report they produced served as a major influence on the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

“That’s the spirit that we celebrate today. A leader, a thinker, a man who always saw that we are all children of God, and that together we can do incredible things that we cannot do alone.”

William Bowen, President Emeritus of Princeton University

Bowen said Hesburgh always valued “openness and mutual respect,” particularly when President Barack Obama was invited to give the commencement address in 2009. When the University faced criticism for the invitation, Hesburgh said Notre Dame was both a lighthouse for Catholic teaching and a crossroads for different beliefs.

“As always, Ted said what needed to be said courageously and clearly,” Bowen said. “A beautifully blended image of the lighthouse and the crossroads will always stay with me.”

Bowen said Hesburgh was also compassionate on an individual level. When Bowen lost touch with his mother after she refused to move out of her home, Hesburgh arranged for her to move to an assisted living facility connected to Notre Dame.

“Believer as he was in the need to be active on the world’s largest stages, Fr. Ted was every bit as committed to helping an aged lady he did not know,” Bowen said.

Joe Donnelly, U.S. Senator, Indiana

Donnelly, class of 1977, said openness and acceptance characterized Hesburgh’s life, through the admittance of women to Notre Dame, his love of South Bend and the Navy and his availability to students.

“The light in his small campus room here in Corby Hall was always on,” he said. “Midnight, 2 a.m. It was for students who may have lost a parent, who were wondering, 'how am I ever going to pay the rest of the tuition bill? How am I ever going to pass my test? I’ve got a broken heart, and it will never heal.' Fr. Ted was our pastor, and he wanted us to all know how loved we were.”

Fr. Paul Doyle, Rector of Dillon Hall

Doyle, who helped take care of Hesburgh as he aged and his vision deteriorated, said he possessed innate goodness and a rich spiritual life, saying Mass daily and often talking with the Blessed Virgin Mary.

Doyle said Hesburgh stopped going to his office on the 13th floor of the Hesburgh Library regularly after Christmas, but recently decided to make one last visit.

“He wanted to talk to Our Lady on the Dome one more time from his office,” he said. “Those who helped Fr. Ted make that visit to his office report that Fr. Ted talked to her from his gut, thanking her and entrusting this place and us to her continuing care.”

Lou Holtz, former Notre Dame football coach

Hesburgh regarded his decision to admit women to Notre Dame as one of his greatest achievements, Holtz said. Holtz said he would ask Fr. Hesburgh why he had decided to make the University co-educational.

"His answer was, I always knew Notre Dame could not be a great educational institution if we continue to eliminate one half of the most talented people in this country," Holtz said.

According to Holtz, Hesburgh was the embodiment of a great leader.

"I asked him, 'What is a leader, Father?' and he said, 'If you’re going to be a leader, you have to have a vision of where you are and where you want to go and how you’re going to get there.' Well, I can tell you, for sure, Fr. Hesburgh had a vision, where he wanted to go and how to get there," Holtz said.

Hesburgh is irreplaceable, but we can repay him by living in a manner worthy of him, Holtz said.

"I always had a saying, 'If you didn’t show up, who would miss you and why? If you didn’t go home, would anyone miss you and why?'" Holtz said.

"Put that question on Fr. Hesburgh. Think of the difference he made in people’s lives.

... But I think if we really want to show the positive influence he had on our lives, we must live the way Fr. Hesburgh would want us to do. This is the only way we can ever repay him."

Theodore Cardinal McCarrick, Archbishop Emeritus of Washington, D.C.

McCarrick said through his devotion to Mary and the Eucharist and his service to popes, Hesburgh “knew what it was to be a faithful priest.” He said Hesburgh's writing and priesthood were faithful to both the Church and the Second Vatican Council.

“We are judged by the fruit of our labors, and this beloved University is his gift — his gift to the church, his gift to our nation, his gift to ourselves, his gift to the future of the world,” McCarrick said.

Mike Pence, Governor of Indiana

Pence said while Hesburgh was a “giant on the world stage,” he always returned home.

“Fr. Hesburgh always came home to Indiana, to South Bend and to his beloved Notre Dame. This community and this state held an unequivocally special place in Fr. Ted’s heart, and I [rise] to say tonight that Fr. Ted held a special place in the heart of people all across this state.”

Harris Wofford, former U.S. Senator, Pennsylvania, and Martin Rodgers, Member of Board of Trustees

In an interview with Thompson, Harris Wofford and Martin Rodgers, class of 1988, spoke on Hesburgh’s role in the Civil Rights Movement, both in the U.S. and at Notre Dame.

Wofford, who served as Hesburgh’s legal counsel while Hesburgh was on the Civil Rights Commission, said that Hesburgh’s biggest challenge while on the Commission was John Battle, the Governor of Virginia, a fellow member of the Commission and a strong supporter of segregation.

“Only Fr. Hesburgh and John Battle thought at the end of the day to drink bourbon, so they began to take turns bringing it at the end of each meeting,” Wofford said.

“They never fought over civil rights but became friends. They talked about family and friendship.

“When it became time to see if they could agree … they unanimously came together and John Battle said, ‘I can’t know Fr. Hesburgh and the Constitution together and not see that something must be done.’”

Rodgers, who as a student helped the Department of Admissions increase the number of minority students admitted by more than 15 percent, spoke of Hesburgh’s impact on integration on campus.

Rodgers’ father was one of the first African-Americans to enroll at Notre Dame and he revered Hesburgh, Rodgers said.

“Back then, when he enrolled and he showed up, his roommate refused to room with him because of the color of his skin,” Rodgers said.

“My dad was alone, he was scared, he was uncertain what would transpire, but he needn’t have been. He needn’t have been because Fr. Ted Hesburgh, who assumed the presidency the year later, his values and the values of the Holy Cross priests were already in the bricks and mortar of this place.”

“He needn’t have been scared and worried because this is the University of Notre Dame, the University of Our Lady, and so the University, back in 1951, told my father’s roommate that he would have to be the one to pack his bags, not my dad.”

Alan Simpson, Former U.S. Senator, Wyoming

Simpson, who worked with Hesburgh on the Immigration Reform Commission, said Hesburgh never “got any soft issues to deal with in America” but approached all his tasks with reasonableness and good humor.

“He was fair, firm, prepared, principled, productive, patriotic and had a grand sense of himself and the world around him, and even the ability to chuckle at himself,” Simpson said. “He served in the trenches — actually down in the foxholes sometimes, when verbal shells were being lobbed in.”

Often drawing laughter from the audience, Simpson told stories about his and Hesburgh’s dealings with minister and activist William Sloane Coffin, Hesburgh’s friendship with Ann Landers and Simpson’s own honorary doctorate and law degree from Notre Dame.

“To me, he was the epitome of grace in man,” Simpson said. “The torch he carried for 97 years lighted many a path and lightened many a burden, and what we already saw in this magnificent life lived was the true essence of religion lived out. Truly we are all children of God; few of us become men of God. He was.”