Notre Dame prides itself on tradition, but there are some aspects of our history that students would prefer never repeat.

Last spring, Residential Life and the Division of Student Affairs announced a policy change that would restrict off-campus seniors from participating in dorm programming. Outcry over the so-called “senior exclusion policy” quickly erupted among the student body. Over 1,000 students gathered outside the Main Building to express their discontent with the exclusionary change.

It turns out the struggle to win justice for off-campus students transcends generational boundaries. For our first edition of From the Archives, enjoy some of the oldest articles from The Observer that discuss the debate over off-campus housing.

Students anticipate the legalization of off-campus apartments

Nov. 3, 1966In The Observer’s debut edition — its very first headliner, to be exact — we are dropped in the middle of the conversation.

At the time, students could not yet live in off-campus apartments, only in homes belonging to South Bend residents “approved by and registered with” dean of students Father Joseph Simons. (Side note — the position of dean of students ceased to exist in 1984. The last person to hold the role was James Roemer (’51). Comparing the 1983 and 1984 staff flowcharts in the Notre Dame Report implies associate vice president for residential life is the position’s closest modern equivalent.)

Seen as excessively restrictive, frustrations with the policy ran high. “Whether real or imagined, the status of the off-campus is tantamount to an outcast,” the article stated.

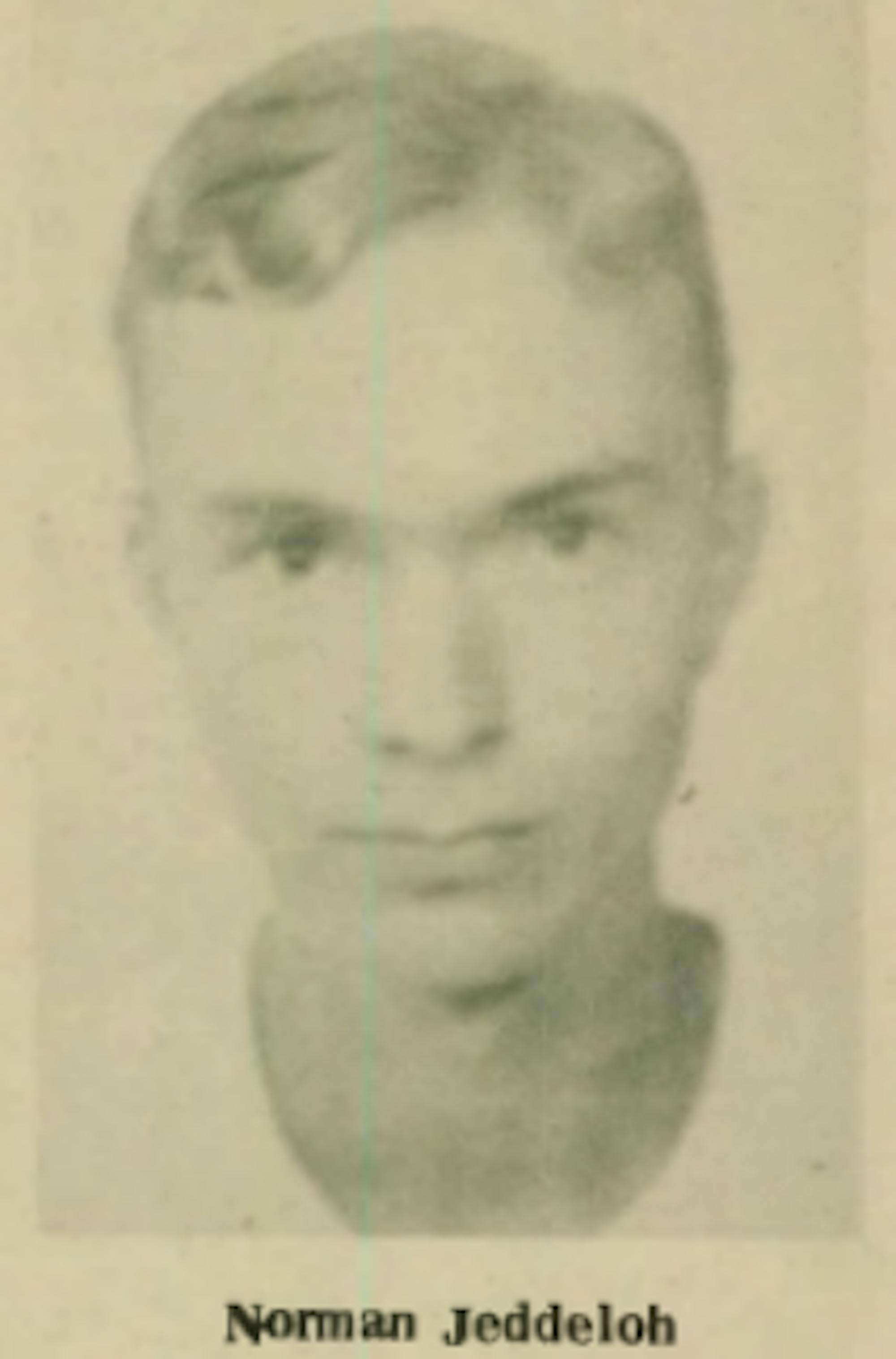

By the time of the article’s publication, off-campus students were already pushing fora more organized community. Then-junior Norman Jeddeloh (’68) founded a judiciary board aimed at outlining “rules and regulations” as well as hearing disciplinary cases for the estimated 1,800 students living off campus during the 1966-1967 academic year.

According to the article, members of the University administration and “off-campus officials” met the night of Nov. 3, 1966, to discuss these students’ futures.

Simons and Jeddeloh denied the meeting would discuss apartment legalization, but several portents suggested the subject would soon be addressed: loosened residential life regulations for on-campus students, a spike in enrollment causing overcrowding and a recent policy change allowing students to have motor vehicles.

Jeddeloh heads the Off-Campus Commission

Nov. 3, 1966 | Bill Brew

The same edition featured a profile on Jeddeloh giving further insight into how he and other students sought to rally those living off campus. Jeddeloh led about 30 others in the Off-Campus Commission, which was divided into a handful of sub-groups including the Off-Campus Judiciary Advisory Board.

The profile also references the development of an off-campus “spirit committee” that would organize events to give off-campus students a sense of community similar to that offered by residence halls.

Hesburgh’s board strikes down apartment proposal

Dec. 8, 1966 | Pat CollinsThroughout the 1966-1667 school year, the debate over off-campus living continued. On Dec. 8, 1966, The Observer reported a six-member board of Trustees (not the University’s current model of the Board of Trustees), which included Father Hesburgh, vetoed off-campus apartment living on two grounds. The first was that on-campus students had “unsatisfactorily responded” to the new freedoms given to them by the University that year. According to the September 1966 edition of The Scholastic, these freedoms included the elimination of curfews for upperclassmen and the ability to have cars on campus. Second, the board had concerns that a growing market for apartments would lower tenancy in Grace and Flanner Hall, which were under construction at the time. (Grace and Flanner were dormitories from 1969 to 1996 but now host staff and faculty offices.)

The piece also estimated nearly 300 of the reported 1,100 off-campus undergraduates live in apartments illegally.

Students petition for off-campus housing autonomy

April 20, 1967Months after the University struck down off-campus apartment housing, the student senate devised a petition to attempt the reform again. The petition called for an “unrestricted policy” that would improve the housing options available to off-campus residents. The authors asserted Notre Dame doesn’t have to be a “residence university” to be a “great university.” Every hall on campus received a petition with space for 50 names. This moment of student activism resembles the student backlash against last spring’s new residential life policies, which include provisions to restrict off-campus seniors from participating in dorm events. Protestors this time around were able to use change.org to gather over 6,000 signatures in favor of reverting the policy.

The authors asserted that Notre Dame doesn’t have to be a “residence university” to be a “great university.”

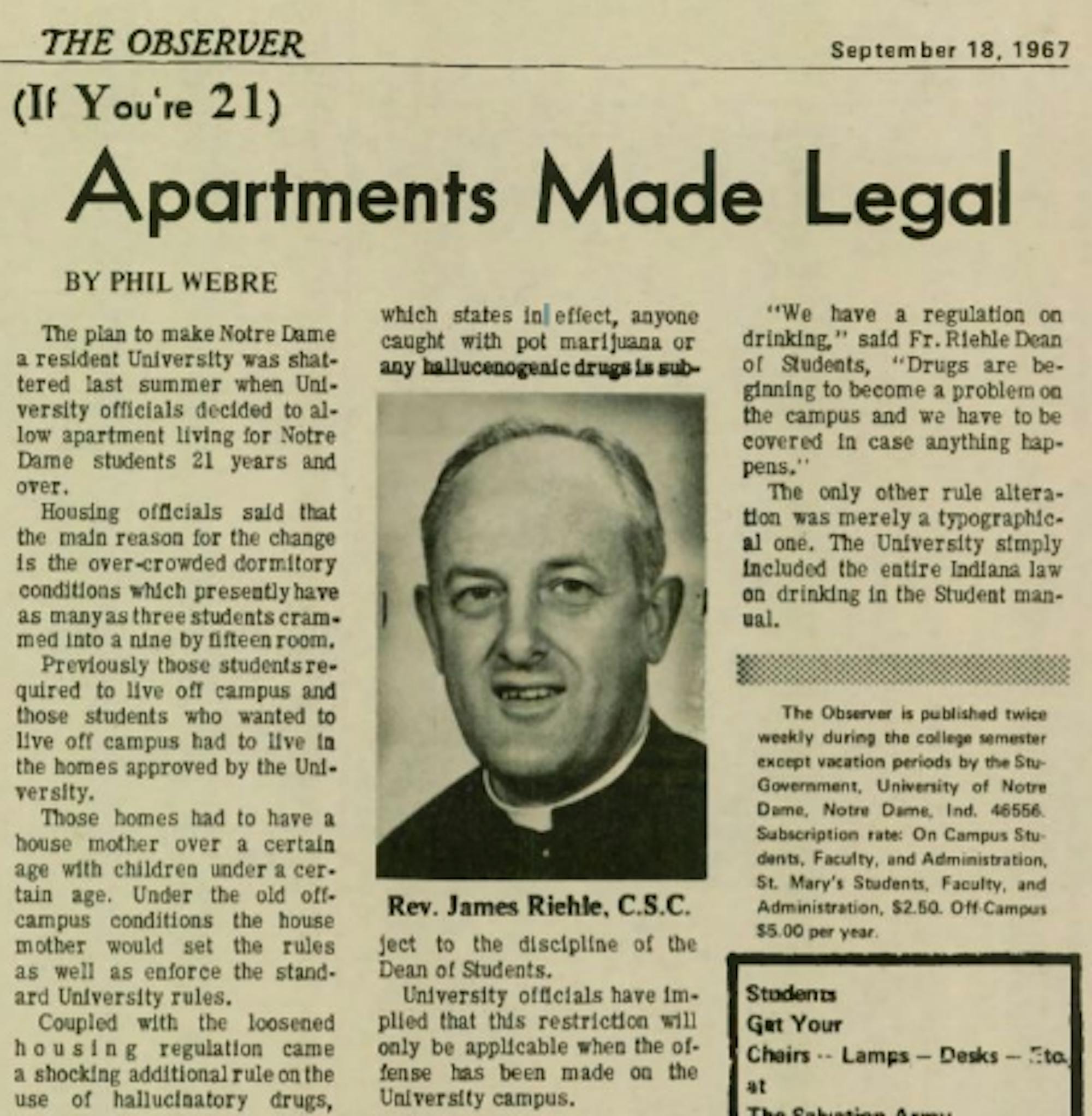

Apartments made legal and ideas for a “resident University [were] shattered”

Sept. 18, 1967 | Phil Webre

Notre Dame officials made off-campus living a possibility for students who were 21 and older to counteract overcrowded dorms. Sound familiar? Before this change, students had to find homes approved by the University if they wanted to leave the dorms. Only homes with a “house mother” above a certain age and children below a certain age were approved. The “house mother” was responsible for setting rules as well enforcing University policy in the household.

This change came hand-in-hand with a stricter anti-drug policy, dictating that “anyone caught with pot marijuana or any hallucinogenic drugs is subject to the discipline of the dean of students [Father Joseph Simons].” According to the article, University officials implied students will only be held accountable for violations if found on campus. The final change was simple — the entirety of Indiana’s drinking law was added to the student manual.