For many months now, hundreds of thousands of protestors have lined the streets of Hong Kong to denounce the erosion of their personal liberties at the hands of China. The city and China have a complex relationship, operating under a “one country, two systems” structure that allows (or is supposed to allow) Hong Kong to remain semi-autonomous and self-governing. This arrangement, it seems, is in jeopardy. Transparently, I don’t know all the details of the complicated situation. But, I also don’t know how relevant they are.

What I do know is that President Xi’s China is a totalitarian regime. The Communist Party of China (CPC), the only party in the state, rules with near-zero room for dissention; they amended their constitution to allow Xi to remain in power for life. I know that it is a state of mass surveillance, that any news or media that could be even slightly damaging to the CPC is censored. I know the government gravely restricts religious freedom, that over a million of the country’s Uighur Muslim population is interned in “re-education camps” that seek to destroy their heritage. I know that the largely peaceful protestors of Hong Kong have been met with tear gas, rubber bullets and beatings for their actions.

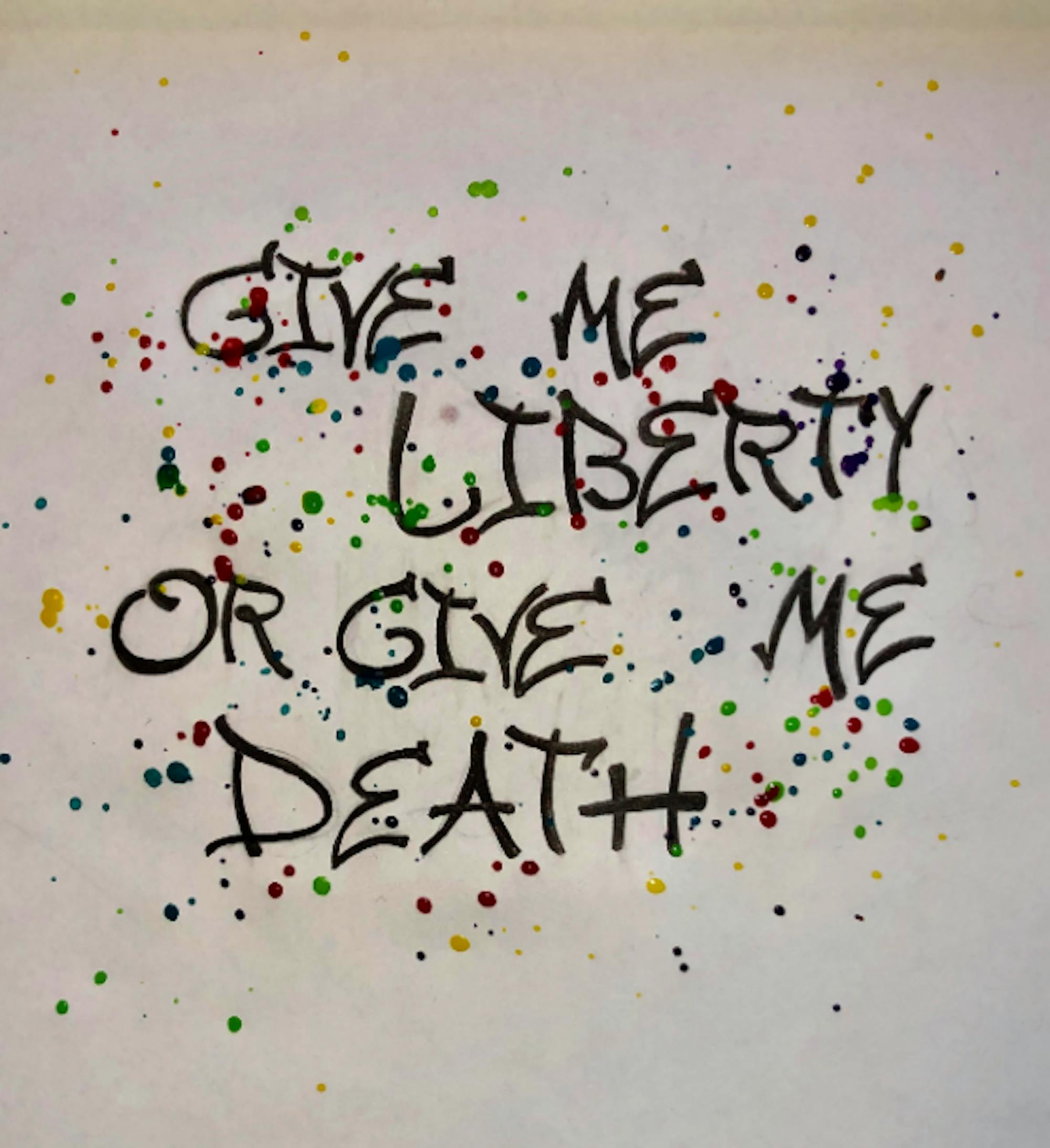

I also know that, in their quest to remain free, the protestors have made an appeal to the United States. Signs and graffitied walls have been emblazoned with the immortal words of Patrick Henry: “Give me liberty or give me death.” It serves a stark and heartwarming reminder that though the centuries and an ocean divide Hong Kong from the American Revolution, its ideals are timeless. It embodies a belief central to the human condition — that tyranny prohibits any of us from truly living, that a person can only truly live in freedom. These are the ideas on which the United States was founded, the ideas the nation still stands for across the world today.

It seems some American-headquarted companies, however, don’t care as much as they should. They are fully content to bend the knee to China and protect their business interests there. Last week, Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey tweeted (and deleted) “Fight for freedom, stand with Hong Kong.” Later that evening, Rockets owner Tilman Fertitta took to Twitter to assert that Morey in no way speaks for the organization. The damage, however, had already been done — the Chinese Basketball Association announced that it has cut all ties with the Rockets organization.

The next day, ESPN’s senior news editor Chuck Salituro issued a memo demanding that any discussion of Morey’s tweet avoid any direct mention of the China-Hong Kong situation. This resulted in commentators awkwardly dancing around the issue and completely misinforming viewers as to the nature of Morey’s tweet and to why those in Hong Kong are protesting.

ESPN and the Rockets are not the only companies acquiescing to China. Apple recently censored the Taiwan flag emoji. Nike removed all Houston Rockets apparel from their Chinese online store. Vans censored a pro-Hong Kong design in their sneaker contest. Audi issued an apology for using an “incorrect” map of China that did not include Taiwan.

As per usual, the worst offender is probably Hollywood. As film has become an increasingly popular medium in the country, and Chinese box-office returns have surpassed those in America, studios have become more and more likely to cater to Chinese audiences. In the new “Star Wars” trilogy, John Boyega plays Finn, one of the story’s main protagonists. Yet Disney chose barely feature him on the 2015 international “The Force Awakens” poster and instead highlighted only white characters. 2012’s “Red Dawn” had to change its antagonist from Chinese to North Korean for fear of backlash. “Pixels” removed a scene featuring the destruction of the Great Wall because “it will not benefit the Chinese release at all.”

Film studios and other American companies are happy to speak out on domestic issues. In 2017, the NBA moved its All-Star Game out of North Carolina in protest of anti-LGBTQ laws. Issues affecting the U.S. are of course easier to comment on, and in most cases, more relevant to the company. But it’s not as if their business crosses no borders. These are multinational corporations that earn a great deal of revenue from Chinese consumers, and they often rely on Chinese employees and manufacturing. They should not watch idly as a totalitarian regime attempts to dissolve the freedoms of Hong Kong.

It’s naive of me to think for-profit companies would act against their bottom lines and in the interest of the greater good. I don’t expect them to. But I also didn’t expect to see “Give me liberty or give me death” on the streets of Hong Kong. I did not expect these protestors to draw inspiration from the American Revolution. I think if anything could get a powerful corporation to take a stand against one of its largest markets, it would be that. Henry’s words remind us that liberty is more important than life. It’s certainly more important than profit.

Patrick McKelvey splits his time between being a college senior and pretending to be a screenwriter. He majors in American studies and classics, and will be working in market research in New York after graduating. If you can't find him at the movies, he can be reached for comment at pmckelve@nd.edu or @PatKelves17 on Twitter.

American companies need to stand up to China

Kerry Schneeman I Observer Viewpoint

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Observer.