Editor’s Note: This is the second story in a two-part From the Archives series featuring Molly Kinder. The first story was published on Monday, Sept. 21.

[embed]https://youtu.be/ZK5kc9UActk[/embed]

Molly Kinder describes her experience as the first woman on the Irish Guard. Video by Colleen Fischer.

After graduating from Notre Dame, Molly Kinder (‘01) adopted a policy of never bringing up her position as the first female member of the Irish Guard. But if she is asked, she will discuss it openly.

Nearly 20 years after her time on the Guard, the Observer's From the Archives team reached out to Kinder — and for the first time, the first Irish Guardswoman reflected on the challenges and lessons of her historical experience.

Meeting the 6-foot-2 height requirement and demonstrating adequate marching skills were not the biggest obstacles to joining and being a part of the Guard — at least not for 6-foot-3 Kinder, known by her peers and mentors for her exceptional marching abilities.

But being a woman was. Kinder said she did not feel her nine fellow Guard members, all men, ever accepted her as part of the group.

“They wouldn't communicate with me. They wouldn't socialize with me. They wouldn't tell me important information,” Kinder said.

Nonetheless, she also said she experienced “very uplifting” displays of support from her family, professors, friends, fellow McGlinn Hall residents and others in the South Bend community.

“There was a lot of enthusiasm from women on campus and women [alumnae],” Kinder added.

Kinder said she believes her time as a Guardswoman was very personally formative — not in spite of, but because of the varying reactions to her new position, as well as the hurdles and the sense of fulfillment these attitudes entailed.

“That kind of crazy experience I went through has really impacted me as a person. It has impacted my career,” she said. “I've done some kind of brave things, like moving to Liberia not long after a civil war and pushing myself to take jobs that were outside my comfort zone.”

Today, Kinder is a David M. Rubenstein Fellow at the Brookings Institution, researching labor policy oriented around women and low-wage workers. Previously, she served in the Obama administration as a part of the United States Agency for International Development. Kinder also received the 2012 Distinguished Alumni Award from Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies.

“It’s easy for me to look back and see how 20 years on, there’s some grace and some growth in [the challenges] as well. I feel really proud of that experience,” she said.

Kinder recalled an especially challenging day, marked by a heartwarming moment. Before a football game, Kinder and her colleagues lined up in front of Bond Hall as part of a customary Guard inspection. The captain would check their uniforms in front of hundreds of fans.

This particular day, former guardsmen watched on — angry, drunken and a bit rowdy, according to Kinder. She said she found this very stressful, as many of these alumni disapproved of her presence on the Guard.

“The University administration had heard from angry [alumni] that these returning Guardsmen were going to come to my first game and cause a problem,” Kinder recalled.

Anticipating disturbances from these former Guardsmen, the University intentionally placed priests and policemen in the area.

“Thank God what they did was, they just ignored me,” Kinder said.

But where there were challenges, there were also rewards.

“And I still tear up thinking about this,” Kinder continued. “There was one incredibly classy [former] Guardsman who came up with his daughter. He came up to me and he said, ‘Molly, welcome to the Guard. This is my daughter. I hope she'll be on the Irish Guard someday.’”

That young girl is probably in her 20s today, Kinder noted — she may even be a student at Notre Dame.

“I hope she’s tall,” Kinder added.

Although Kinder’s experience with the Guard ended 20 years ago, she expressed a belief that her story can shed light on today’s social issues. Reflecting on the challenges she encountered, Kinder relayed two messages — one for aspiring trailblazers, the other for institutions in power.

If she could talk to the young girl who approached her, Kinder said, she would emphasize not only the challenges of breaking barriers, but also the rewards.

“When you're the first to do something that is groundbreaking, it's not just the achievement of doing it, it's the consequences of navigating the aftermath,” she said. “... I had the most challenges, but I also had the greatest rewards.”

When Kinder became the first Guardswoman, her friend Michael Brown was the University’s first Black leprechaun. Reflecting on the progress they both spearheaded, Kinder commended all minority groups who break glass ceilings, such as other women, LGBTQ individuals and people of color: “I just applaud anyone for doing this. I think it matters so much.”

And addressing institutions in power, specifically the University’s administration, Kinder spoke of the Notre Dame community’s unyielding adherence to tradition, as well as its responsibility to evolve when necessary.

“Notre Dame is so steeped in tradition,” Kinder said, referencing the male-dominated spaces of religion and football, both central to the University’s culture. “It’s a really tough place to balance tradition and progress. Because if you don’t evolve your traditions, you’re just stuck in the past, and there’s no room to evolve.”

Kinder also recognized the significance of her story within the context of today’s social climate. With the hindsight of the #MeToo movement and ongoing gender inequities, her story carries a new weight.

It’s not just about the trailblazers, Kinder argued: “It’s about all of us — particularly ... those who are setting the rules.”

But since Kinder, the University has grappled with many other issues of marginalization. Progress at Notre Dame seems to occur in stages, Kinder noted. Following a focus on women’s issues at the turn of the century, attention turned to the acceptance of LGBTQ students. And today, the University is grappling with rising racial tensions on campus and beyond.

But in all of these issues, Kinder identified one common thread: apathy from the administration forcing students to take matters of activism into their own hands.

“It shouldn’t be up to the Black students on their own to own this and have to navigate this. It’s up to everyone. It’s up to the administration. It’s up to the culture. We’re all in this. It’s not fair to leave this to those who are breaking the barriers.”

And speaking specifically to women’s issues that still pervade the University’s culture, Kinder challenged the administration to spark progress in a systematic manner.

“It's not just up to the girls to just beat down barriers and be the heroes,” she said. “I think we, as an institution and as a culture, have to do better to meet them where they are and make it better.”

‘We have to evolve tradition’: 20 years later, Molly Kinder reflects on her experience as first Irish Guardswoman

Diane Park | The Observer

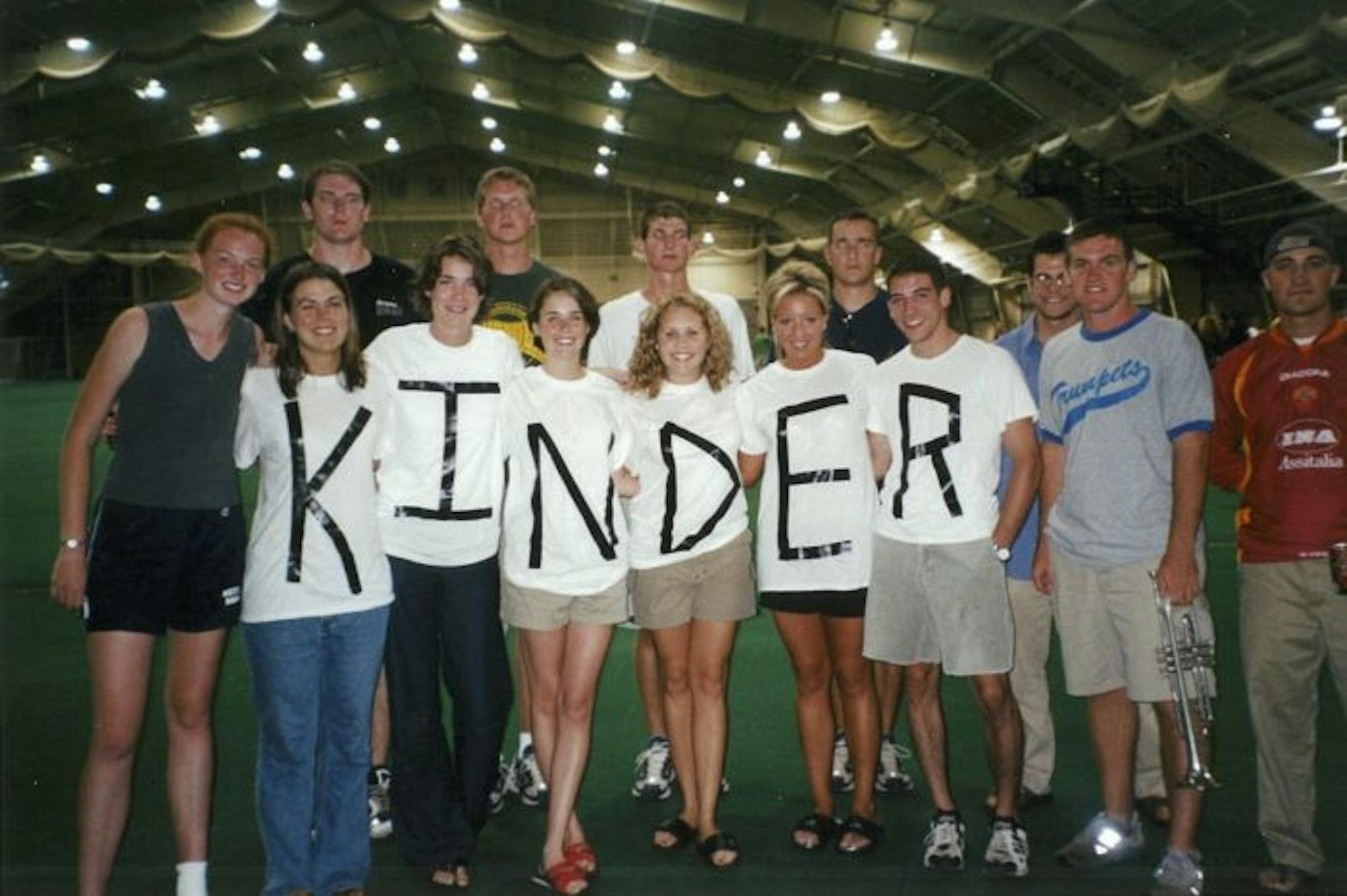

Kinder's (left) roommates and friends support her on the day of the tryout in fall 2000 by wearing shirts spelling her last name.

Kinder (right) standing at attention during a Guard inspection in the fall of 2000, as returning Guardsmen look on. Most of them ignored her, Kinder said.

A former guardsman and his daughter approach Kinder during Guard inspection before a football game in the fall of 2000.

Kinder (center) poses with cheerleading team members and Michael Brown (right), Notre Dame's first Black Leprechaun, during a game day in the fall of 2000.

Courtesy of Mary Therese Kinder