What do journalists do when the details of an event aren’t quite adding up?

At The New York Times, they often turn to Malachy Browne.

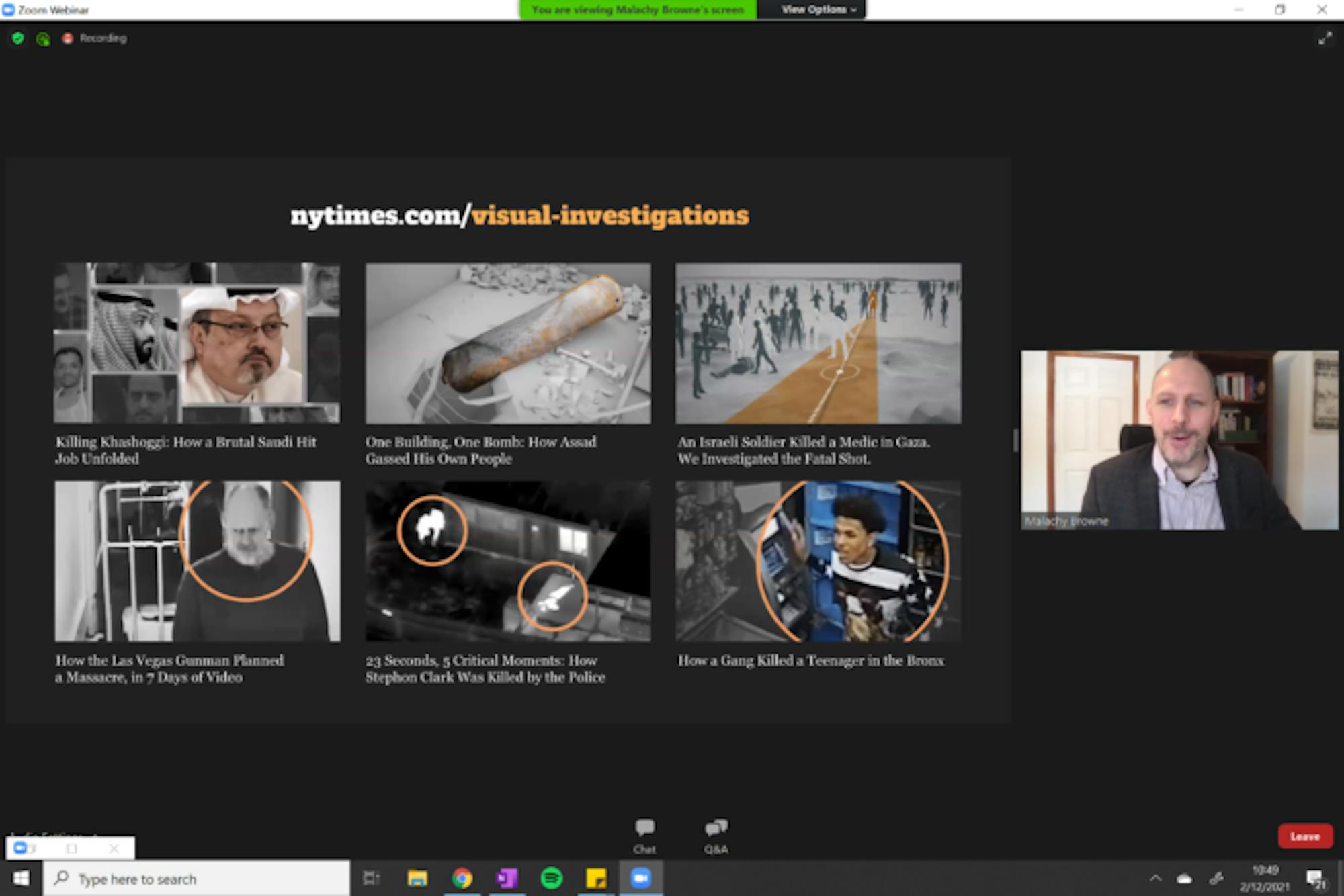

Browne spoke to Notre Dame professor James O’Rourke over Zoom as part of the Ten Years Hence lecture series on Friday. He works with a team of investigators and computer scientists to recreate frantic moments from some of the past decade’s most memorable tragedies. The team is called Visual Investigations, and their goal is to use digital forensics to uncover stories.

“There’s an overabundance of information out there that allows you to get to the truth of an event, or a debate, or a contention or argument, a denial by a government around the human rights abuse,” Browne said. “And that's a lot of what our work is, doing that digging, digging, digging through the online sources, as well as getting on the ground and talking to people.”

The examples in his presentation demonstrated not only the scope but the gravity of their work: reconstructions of the 2017 Las Vegas mass shooting, a 2018 Syrian chemical attack by the country’s leader Bashar al-Assad, the 2020 shooting of a Palestinian medic by Israeli soldiers, the 2020 murder of Breonna Taylor, and the repeated and continuous bombing of Syrian hospitals by Russian military.

Browne said their first investigation, the Las Vegas shooting, was motivated by a mutual distrust between “tight-lipped” authorities and online communities who sensed a cover-up.

“We sought to develop a timeline of what happened independent of the authorities using the videos that people kept filming, despite the rampage of bullets,” he said.

Their process included sourcing those videos and overlapping them to create a rough outline of when the shooting started and stopped. The open-source timestamps on most videos from social media allowed them to create a completely accurate timetable of events. They even recruited a graphics reporter to create a 3D-model of the shooter’s hotel room.

“It's almost what the police would do when they're investigating, collecting live streams and police body cam footage, 911 calls and all the rest of it,” Browne said.

After that first award-winning investigation, the team took off. They received the 2020 Pulitzer Prize in International Reporting for their story, “Russia Bombed Four Syrian Hospitals. We Have Proof.”

“A lot of this involved data journalism. There are many different organizations who have been documenting attacks at hospitals and other sites,” Browne said. “It has been the most documented war that we've seen. And that has valuable evidence for us.”

During the Q&A portion of the event, Browne estimated that only about 50 to 100 people in the world do what he and his team do. Part of the challenge is access — Browne said he has cultivated relationships with satellite companies to get copies of their images.

“It's the same as like wire photography for us, except there's evidence within it,” he said.

Overall, he said, contributions from the public have played a critical role in many of these investigations. Carefully cross-checking their evidence with the team’s own findings can turn a hunch into a publishable fact.

“We see this very much almost as a collaboration between sources who are documenting what's happening on the ground,” he said.

The Ten Years Hence program will continue on March 12 with Suzanne Spalding, senior adviser for Homeland Security and director of the Defending Democratic Institutions project at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

NYT investigator Malachy Browne speaks on recreating crime scenes

Chris Parker

Malachy Browne, of The New York Times, gave a Zoom lecture Friday discussing the works of the Visual Investigations team, which uses digital forensics to reconstruct events and uncover the truth.