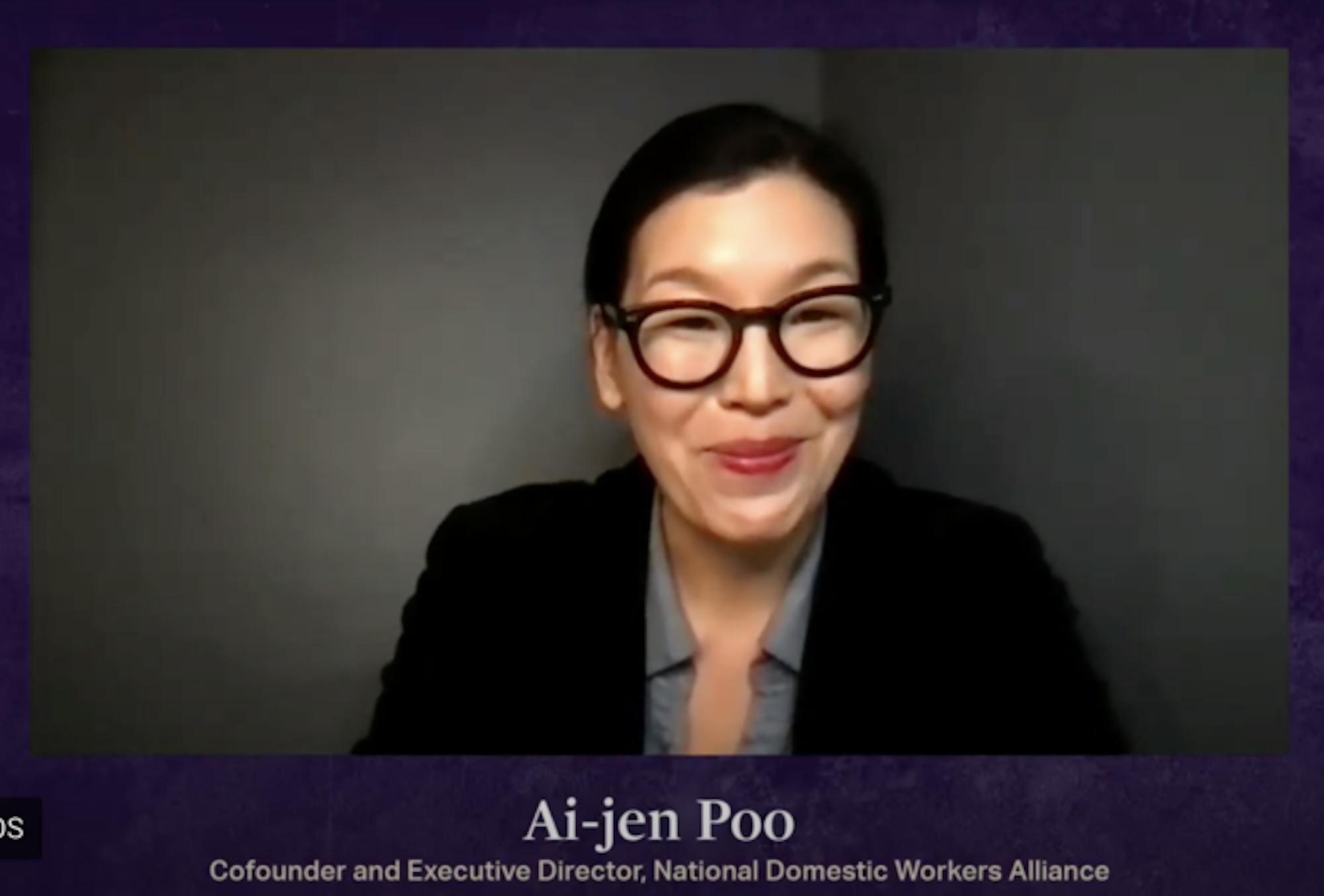

Ai-jen Poo described the work domestic workers do as “fundamental to human life” in a virtual lecture hosted by Notre Dame's Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies Thursday evening.

Poo is the co-founder and executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA). Since its launch in 2007, the organization has helped pass domestic worker bills of rights in a number of states which ensure home care workers, nannies and house cleaners have basic labor protections.

The virtual event was the first of the Asian American Distinguished Speaker series and was moderated by provost Marie Lynn Miranda.

Early life

When she was a student, Poo became involved in an organization called the Committee Against Anti-Asian Violence, which was founded in response to the wave of anti-Asian violence in the 1980s. She said her experiences fighting for justice as a student catalyzed her interest in activism and eventually led her to organizing domestic workers in the Asian community and beyond.

Raised by her mother and grandmother, Poo said she was always inspired by both of them to work while caring for her and her sister.

Poo’s mother immigrated to the United States from Taiwan in her 20s to study chemistry. She went on to medical school, caring for Poo and her sister while also studying to be a doctor.

Poo said as she grew older, she began to fully understand what her mother’s role was as a physician.

“A big part of it was helping people in their most vulnerable and fearful moments, moments of illness when they’re confronting their own mortality and to actually face those moments with courage,” Poo said.

As her mother treated the patients with the worse cases of cancer, Poo said she learned to face human suffering “straight on.”

Spending time with her grandmother as a child while her mother worked, Poo learned the value of optimism.

“She really did believe that no matter how hard things got as long as you stay present in the moment, you can find a way forward,” Poo said.

Activism and workers’ rights

As she began working with Filipino domestic workers, Poo learned domestic workers had far less protections than domestic workers in other countries and faced significant exclusions from basic labor rights.

“That exclusion has deep roots in the legacy of slavery in America,” Poo said.

Since many of the first domestic workers in the United States were enslaved African women, Southern members of Congress refused to support the passage of fair labor laws for domestic workers in the 1930s.

“Our laws and culture have essentially made invisible and vulnerable some of the most important work that happens in our economy and the people who do it,” Poo said.

While nannies, house cleaners and home care workers allow others to go to work while children are taken care of, Poo said it was frustrating to see these workers face exclusion from rights and protections as workers.

“The work that domestic workers do is fundamental to human life,” she said. “It is the work of caring, of nurturing, of meeting human need with compassion.”

Poo said it has been challenging to formulate a way to advocate for domestic workers rights because domestic workers do not have communities in the same way other types of American workers do.

“We can't collectively bargain, which is a traditional means through which workers improve their conditions. There's no collective, there's no one to bargain with,” Poo said.

In order to overcome this challenge, Poo said her organization focuses on building power for workers in three different dimensions. The first dimension is political power to change policies to benefit domestic workers. The second is narrative power, which Poo said serves to “tell the story of why things are the way that they are in the world on your terms.” The third dimension is economic power.

Working with the director of Roma, NDWA launched a campaign for viewers of the film to reflect upon the work of nannies and home workers and consider what can be done to better recognize their work.

In addition, NDWA created a portable benefits platform to make it easier for domestic worker employers to contribute to their employee’s benefits. NDWA also created a messenger chat bot of Facebook which allows them to communicate with the over 280,000 domestic workers.

“We try to be creative and in order to shape the narrative and to change policy and to do the things that would make life better for domestic workers,” Poo said.

Domestic workers in the pandemic

Poo acknowledged the difficulties domestic workers have faced throughout the pandemic, as many have lost their jobs and thus, their source of income. She recalled a Zoom meeting early in the pandemic, where one of her members held up her phone to the camera to show there was only one cent left in her bank account.

Although Poo said there is a tremendous amount of suffering in the country right now, she thinks the pandemic can help the country reimagine laws and policies to benefit workers.

“To me, that's about making sure that we have good jobs, that we have a minimum wage that people can survive on, that everyone has access to a safety net and basic benefits,” Poo said. “And it also means that we have a strong care infrastructure that imagines if at every stage of life, we could take care of our families and the people that we love, and know that our caregivers were well compensated and secure for taking care of their own families too.”

Poo said Americans should have the courage to reject an economy where people work hard but still struggle to survive.

“That is unacceptable in a country with this much talent and beauty and opportunity and grace,” Poo said.

With the acknowledgement of essential workers during the pandemic, Poo said she hopes the shift in the way Americans see what kinds of jobs are essential will remain after the pandemic.

“There are moments like now, where the potential to make the invisible visible and to cement that visibility is incredibly great,” Poo said. “And the way that we cement it is, I think, through trying to make that the new normal.”

Activist Ai-jen Poo speaks on the fight for domestic workers’ rights in America

Ai-Jen Poo

Ai-jen Poo, co-founder and executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance spoke at a virtual lecture Thursday evening.