Korean American student reflects on Virginia Tech shooting

April 5, 2012 | Edithstein Cho | Researched by Chris Russo

In her 2012 Viewpoint column for The Observer, Edith Cho (‘14) offers a reflection on the parallels of the shooting death of Trayvon Martin and the Virginia Tech Massacre. Cho makes specific mention of her Korean American background, offering yet another layer of insight in light of the fatal shootings at three spas in and around Atlanta.Penned in the wake of Martin’s death, Cho reflects on her mindset nearly five years prior, on April 16, 2007, the day after Seung-Hui Cho shot and killed 32 people, including himself. She describes the strong “chord of fear” that struck her and her mother. The dread was so overwhelming she almost did not attend school the day after the shooting. Although she attended high school over 1,000 miles away in the Twin Cities, she was concerned that her race and her last name, “Cho,” would spur misplaced retaliation from grieving classmates.Cho was not alone in her concerns. Student newspapers voiced concerns of future harassment of Asian American and Korean American students on campuses. The fear also spread through the Korean American communities at large. With over 1.7 million Korean Americans in the U.S., Cho notes that “communities across the nation froze when they learned” about the massacre.This fear of racial vilification stems from past experiences when Asian Americans have been isolated during times of hardship. Social and political movements have isolated Asian Americans during periods of mass immigration at the turn of the 20th century, World War II and the COVID-19 pandemic. Cho also cites the death of Martin and the 1992 Los Angeles riots as examples of racialized conflicts that have transcended to affect ethnic communities at large. Fearing her accumulating makeup work, Cho chose to attend school on April 16, 2007. But she was shocked by her classmates’ general obliviousness regarding the shooting, reflecting “what turned my world around seemed to have affected no one else.” She was disappointed by the response because it seemed repressive rather than constructive. Aware of her shared Korean heritage with the shooter, Cho was prepared to “distance [herself] from the shooter’s identity,” highlighting what she referred to as undermining “my belief in the dignity everyone deserves.” She expands this concern to include what she witnessed on campus regarding the Trayvon Martin case. “By not talking about it, we will not learn about how different individuals are affected,” Cho wrote.This notion has survived in the years since Cho’s column was published. Following the deaths of eight people in the Atlanta spa shooting, including six women of Asian descent, Cho’s concerns remain a powerful reminder. Obliviousness only avoids the discomfort that stems from discussions of race. Without conversation, “we will not know how race plays a role in the workings of our world.”2002 production of Asian Allure educates, entertains, reaches new heights

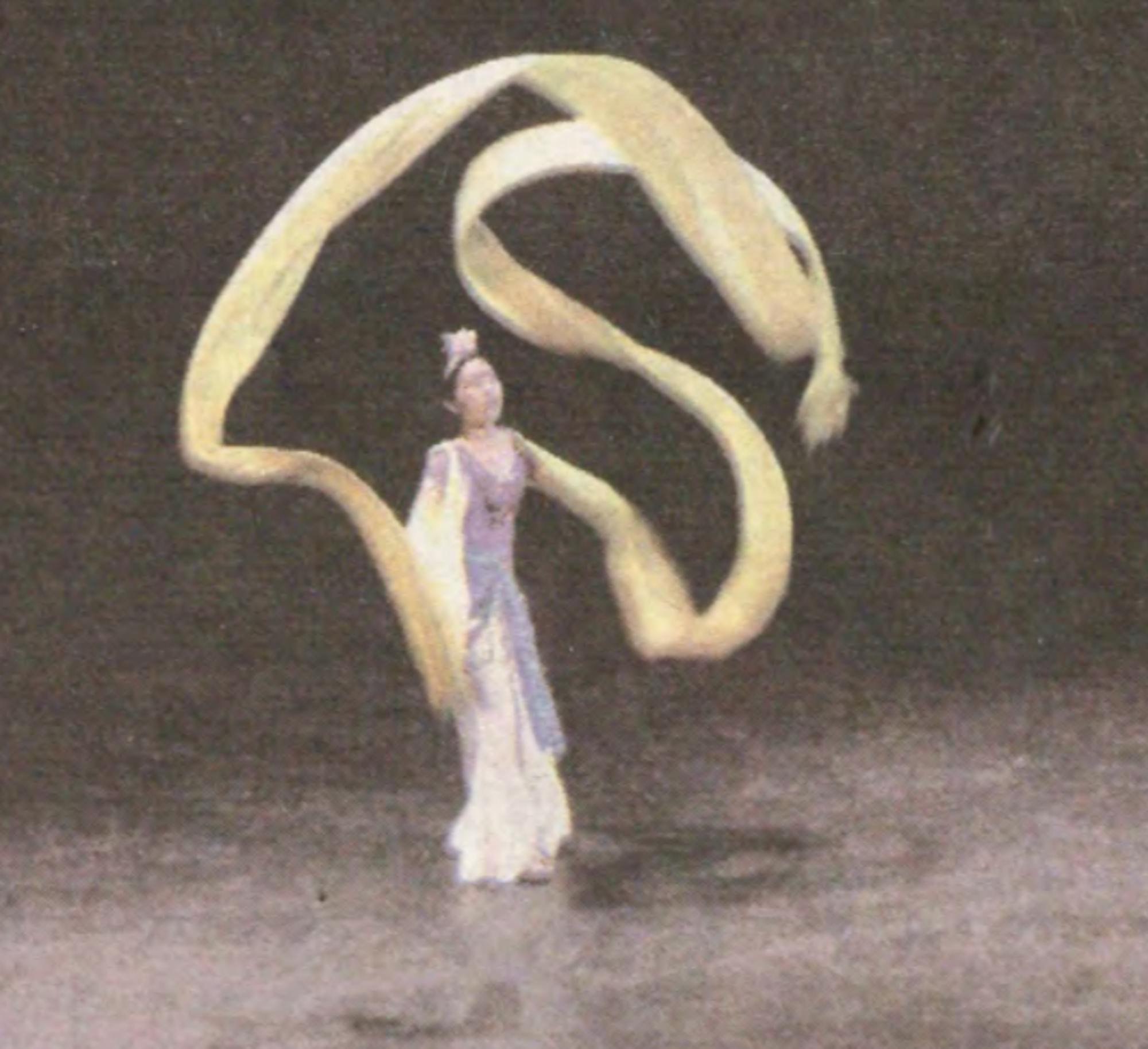

Nov. 8, 2002 | Linda Skalski | Researched by Evan McKenna

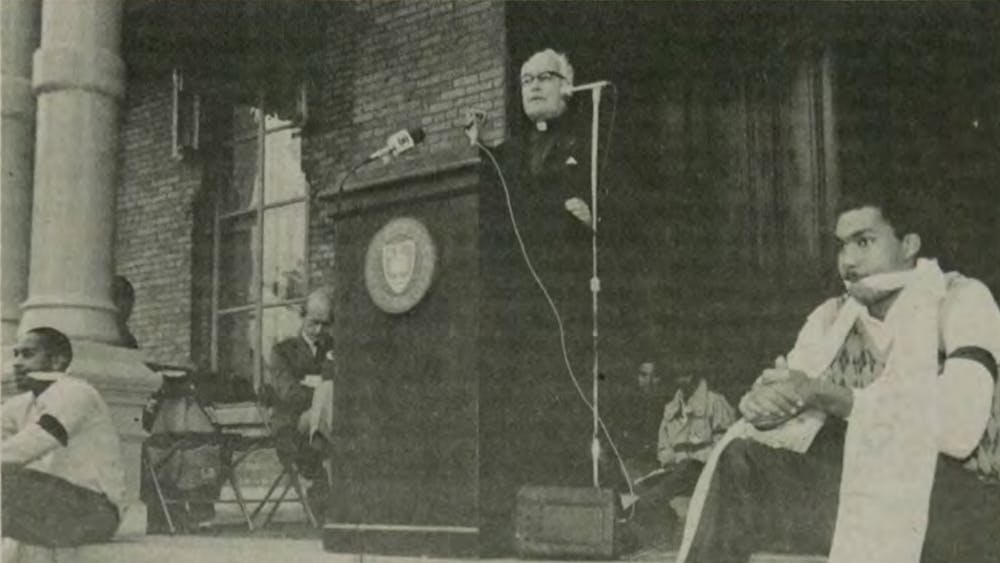

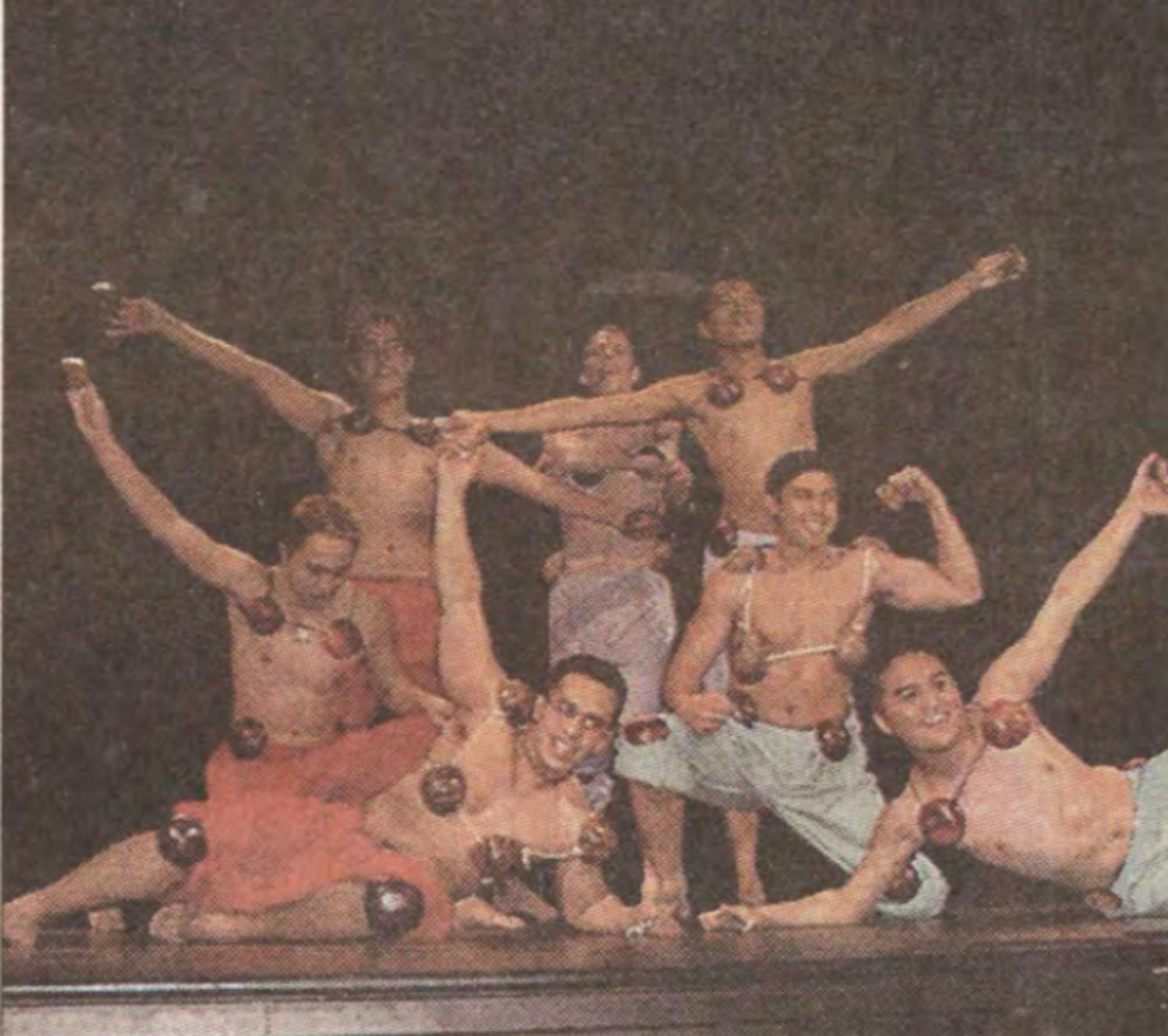

On Nov. 8, 2002, News Writer Linda Skalski (‘05) previewed the Asian American Association’s production of Asian Allure, a set of performances dedicated to showcasing the broad range of Asian American culture and tradition through song, dance and fashion. The 2002 production adopted the theme “Generazians: Bridging the Gap,” in hopes of encompassing both traditional and modern Asian culture through its performances.

Asian American students celebrate their heritage in The Observer

Nov. 4, 2011 | Trixie Amorado | March 17, 1994 | Theresa Lie | Researched by Jim Moster

Asian American students at Notre Dame have found many opportunities to celebrate and share their heritage with the community. Prior to the Asian Allure fashion show in 2011, sophomore Trixie Amorado (‘14) wrote to The Observer discussing “[her] Asian home at ND” and what Asian Allure means to her.Growing up, Amorado had little pride in her Filipino culture. While she “wasn’t ashamed of being Filipino,” Amorado did not think her culture was worth sharing with others. After arriving at Notre Dame, Amorado’s attitude changed. She found herself surrounded by Asians for the first time in her life. Many of her Filipino friends understood her family’s traditions and language. Soon, she was calling her Asian friends her “second family, full of ‘ate’s’ (big sisters) and ‘kuya’s’ (big brothers) and ‘adings’ (little sister/brother).” In light of all the Asian community had given her, Amorado felt a deep joy participating in Asian Allure.In 1994, another student wrote to The Observer connecting her background to a community event. Junior Theresa Lie (‘95) was born and raised in the United States but was surrounded by Chinese culture her whole life. Although her parents were born in the Philippines, both sets of her grandparents were Chinese. Lie embraced the uniqueness of her background.“Everyone is different and unique in some way, and I believe that having a background different from ‘the norm’ is something that one should be proud of,” Lie wrote. Lie wished to partake in the Asian American Association’s Asian Heritage Week by sharing her story. The purpose of Asian Heritage Week, Lie wrote, was “for AAA members to share our varied and different backgrounds with each other and our fellow non-Asian Domers.”One piece of Lie’s culture that she shares is a religious ritual performed by her grandparents. Anticipating that the reader might find this strange, Lie asks the reader to think about how strange one’s own culture would sound to an unacquainted party.