The influence of Hispanic Americans, from past to present

April 12, 1990 | Paul Peralez | Researched by Spencer Kelly

In his 1990 Viewpoint column, first-year student Paul Peralez (‘93) wrote about the emergence of Hispanic Americans in American culture and politics. Thirty years later, this trend has only continued.Peralez, who founded the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC) at Notre Dame, noted the increasing Hispanic-American population at the time. In 1990, there were around 20 million Hispanic people in the country, or roughly 10% of the total population. Now there are over 60 million Hispanics in the U.S. At 18% of the total population, they represent the nation’s largest non-white demographic.Peralez also lauded the political influence of the Hispanic population. He noted that candidates in the 1988 presidential election frequently courted Hispanic voters. George H.W. Bush was wont to mention that his daughter-in-law was Mexican. And in what Peralez called “a moment which Hispanics will long remember,” Michael Dukakis burst into Spanish during his speech at the 1988 Democratic National Convention. Dukakis was greeted with raucous applause, and one man in the crowd began waving the Puerto Rican flag.This political influence has grown even more today. A recent study from UCLA’s Latino Policy and Politics Initiative found that Hispanic voters were the decisive factor in the key battleground states of Arizona, Georgia and Wisconsin during the 2020 presidential election.But influence has also been increasingly extended to representation in government. There are currently four Hispanic Americans serving as Cabinet Secretaries in the Biden Administration, and the 117th U.S. Congress has a record 59 Hispanic Congresspeople.Finally, Peralez clarified a point on the heterogeneity of Hispanic America. The umbrella term of “Hispanic” often fails to convey the myriad cultures of which it consists. However, he expressed a sense of unity amidst the diversity, a sentiment that would surely continue to uplift their influence in America.

Notre Dame’s first female law school graduate: The life and legacy of Grace Olivarez

Feb. 25, 1970|Mark Walbran | Feb. 26, 1970 | Mark Walbran | Feb. 27, 1970 | Mark Walbran | Researched by Lilyann Gardner

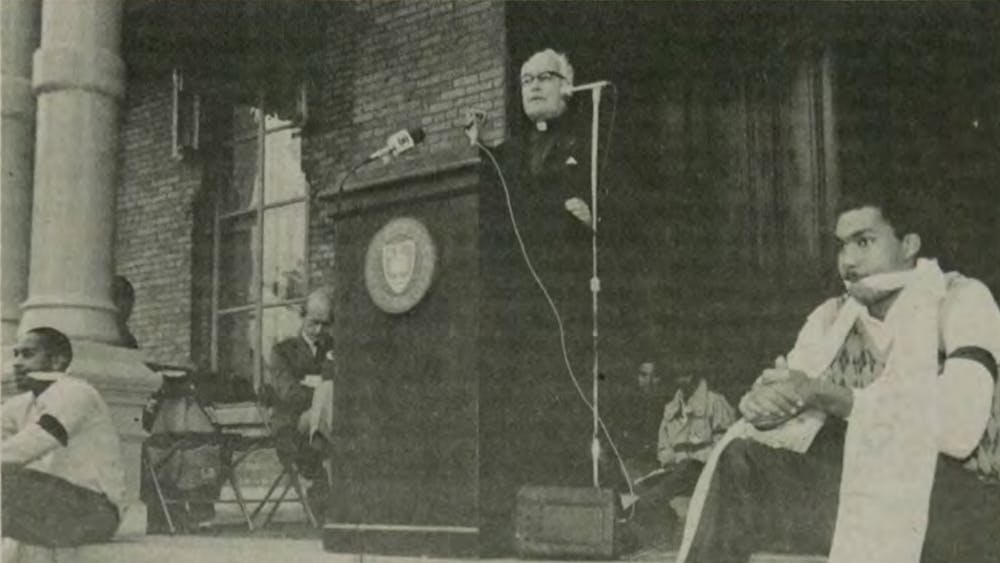

The glass ceiling shattered when trailblazer Grace Olivarez stepped foot into Notre Dame Law School on a bright July day in 1967. Olivarez, a Mexican American and native Arizonan, made history as the first woman to receive a J.D. from the University’s law school. The Observer’s Mark Walbran (‘71) detailed her remarkable journey to Notre Dame in a three-part series.Mrs. Olivarez’s experience as a Mexican American shaped her outlook on life and led to her investment in promoting equality in marginalized Hispanic communities. Growing up in a segregated town, Olivarez cited that she encountered discrimination within her elementary schooling in which white teachers would shame their students for speaking Spanish, despite the fact that only Spanish-speaking students were allowed to enroll at that school. “You grow up with a distorted image of yourself,” Olivarez told The Observer. “If one week you are in the teacher’s good graces, you swear that the teacher is right. You disown everything that even smacks of Mexican or Spanish. But then if you have a falling out with the teacher, your mother starts looking real good and the teacher looks like an ogre. So you grow up in total confusion.” The mistreatment of Hispanic children contributed to high dropout rates among high school students. Mrs. Olivarez herself did not complete her high school education and instead enrolled in a business school to learn stenography and bookkeeping. After moving to Phoenix, Mrs. Olivarez worked at a small firm before landing a position within a bilingual advertising agency. One day, early in Olivarez’s career, the agency found themselves in a conundrum when their radio announcer was a no-show. The radio station threatened a breach of contract, but Mrs. Olivarez answered her agency’s cry for help by temporarily filling in. Mrs. Olivarez’s brief stint as a radio announcer for the advertising agency led to a full-time career. She quickly gained fame as “that lady who spoke Spanish over the radio.” Olivarez became the Hispanic representation in the media that so many people were searching for — and her influence did not stop there. Outside of her day-to-day job, Grace Olivarez worked with the impoverished in Maricopa County, Arizona and volunteered at her local YMCA. Her employment with the KIFN radio station allowed her to share educational programs on food, health, immigration laws and social security. The social work and philanthropy resulted in the Choate Foundation contacting Olivarez in 1962. She soon found herself working for the foundation full time, creating a motivational program to help improve the school work of minority children. That same year, Mrs. Olivarez met University President Emeritus Fr. Theodore Hesburgh at hearing for the Civil Rights Commission in Phoenix. Hesburgh was greatly impressed by Olivarez’s passionate speech on discrimination, but it would not be until 1966 that they would meet again.At that second meeting, Fr. Hesburgh could sense frustration from Olivarez. This was an accurate observation, as she was struggling to see her positive impact on the impoverished communities of Arizona. Fr. Hesburgh immediately suggested that with an education, more people would be willing to listen and help her work toward ending hunger and decreasing poverty. Waiving the normal entrance requirements, he offered her a spot at Notre Dame Law School. Mrs. Olivarez was hesitant about Fr. Hesburgh’s proposal, and also received a letter from the head of the law school, Dean O’Meara, voicing his doubts about her ability to complete law school. However, the doubt did not deter her. “I may not always agree with some of Father Hesburgh’s ideas,” Olivarez said, “but I would defend him with cape and dagger.” And with that, she accepted a spot in Notre Dame Law School’s Class of 1970.

‘A gift from God in our midst’: Fr. Patrick Neary reflects on Hispanic experience at Notre Dame

Sept. 22, 1994 | Fr. Patrick Neary | Researched by Christina Cefalu

In 1994, Fr. Patrick Neary shared his experience with the Hispanic community at Notre Dame in a Sept. 22 Campus Ministry column with The Observer. Fr. Neary reflected on his initial inability to understand the ostracization felt by his Mexican American friend at the University during his undergraduate years, reassuring him, “I don't see you as different. And everyone likes having you here.” Fr. Neary said he was unable to recognize the culture shock felt by many Hispanic students at Notre Dame.When Fr. Neary returned to the University 12 years later as a Holy Cross priest, he began his work with Hispanic students through Campus Ministry. He praised the enriching, unique culture brought to campus by Hispanic students, writing of the community’s “reverential love for family life, its marvelous sense of community celebrated through fiesta, a deeply rooted Catholicism [and] an authentic and consistent devotion to Mary.” Fr. Neary joyfully watched the community grow from 5% of the student body to 10% during a five-year period of his time in Campus Ministry.Through his work, Fr. Neary recognized the difficulties facing Hispanic students at Notre Dame. He charged University students “take a personal interest in their culture, history, and experience” and to rid themselves of the expectation for the Hispanic community to “just be like us.”“We should not assume that they will simply ‘fit in’ at a university very different from their lived experience,” Fr. Neary wrote. “Certainly we share a Catholic faith, but Catholicism abhors, by its very universality, assimilation and sameness.” Neary also wrote that many Hispanic students voiced to him that Notre Dame had a “pivotal role” to play “in shaping their futures,” but called for the institution to battle the cycle of poverty that many Hispanic communities face by recruiting more Hispanic prospective students and providing additional scholarships.Fr. Neary’s call stands the test of time. Today, the student body must continue to celebrate the rich culture the Hispanic community brings to Notre Dame, and work to make campus a place where Hispanic students are able to live authentically.