A worker shortage is rippling across the country, and the Notre Dame campus is also feeling its impact.

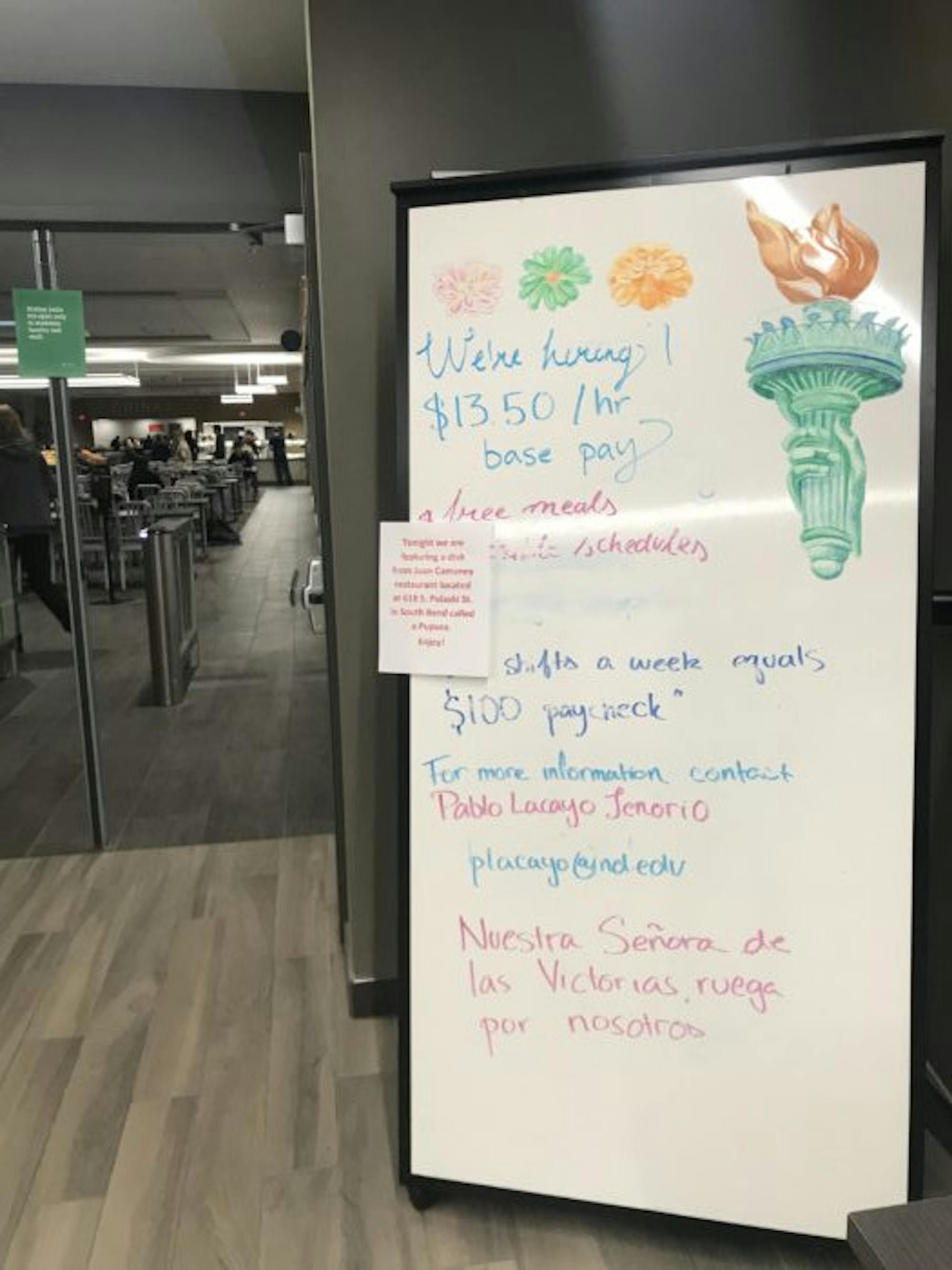

Whiteboards encouraging workers to join the Campus Dining staff and shortened Taco Bell hours highlight the underlying labor shortage on campus.

The problem is exacerbated by both nationwide labor shortages and lower levels of student employment.

“As has been widely reported, many organizations are currently finding it a challenge to recruit and hire new employees,” University spokesperson Dennis Brown said. “The University and our region are not immune to these challenges and we are certainly seeing fewer applicants for our open positions.”

Notre Dame prides itself on offering benefits and wages far above the regional average. In order to attract employees this academic year, Brown said, the University increased local advertising and offered signing and referral bonuses for some positions.

Due in part to a hiring freeze in place from mid-March 2020 to June of this year, Notre Dame has slightly more job openings now than this time last year, Brown added.

Undergraduate students have not jumped at the opportunity to fill these positions.

In the 2020-2021 school year, around 15% of undergraduate students held a job on campus. Though Notre Dame does not have exact numbers for this school year, Brown said undergraduate employment has decreased.

At North Dining Hall (NDH), lead student manager junior Pablo Lacayo said he has noticed a strain on employment.

“Given the more challenging circumstances the tail end of the pandemic has generated, I do feel a greater emphasis has been required from the student [recruiting] program’s behalf,” Lacayo said in an email. “There’s a nationwide trend going on right now that has come to impact us as well.”

Lacayo works almost every dinner hour, the dining hall’s busiest shift from 4:30 p.m. to 9:30 p.m., to help fill the gaps. Lacayo works just under 20 hours a week, the maximum amount a Notre Dame student is allowed to work.

“The dining halls are indispensable and irreplaceable at Notre Dame, at North Dining Hall alone over 5,000 meals can be served on a single weekday … no other option than getting things done exists,” Lacayo said. “Given the expectations of my position, I think taking on the extra hours can be considered a call of duty.”

Lacayo said he focuses his attention on the wash room, a less glamorous but vital part of the dining hall's operations.

“My shifts routinely revolve around the dish room, one of the most important elements needed to keep NDH running,” Lacayo said. “There has to be constant action to make sure that the dining room is always adequately stocked in terms of plates, cups and silverware.”

When recruiting, Lacayo said he emphasizes that the dining halls offer the highest wages — currently $13.50 an hour as base pay — and the most flexibility of any on-campus job.

For student employees, a limited worker supply can also be a positive. Dylan Wachula, a first-year student and employee at South Dining Hall, said he appreciates the flexibility brought on by the labor shortage.

“It’s nice that I get to pick my own shifts,” Wachula said. “The worker shortage seems to have affected the functions of South Dining Hall as they have been very flexible when you come in.”

Notre Dame economics professor Eva Dziadula said worker leverage over wages, hours and benefits is a possible upside of the current labor shortage.

“Conditions for workers are currently improving,” Dziadula said. “Wages have gone up more than we’ve seen in a long time.”

Post-pandemic, workers are harder to replace, meaning they have more negotiating power with their employers. The source of the shortage and resulting worker leverage comes down to supply and demand, Dziadula said.

“There is a reduction of supply and the prices go up,” Dziadula said.

With more job openings and fewer people able to work due to the COVID-19 pandemic and other circumstances, companies have more demand for employees, but workers are in short supply. As a result, prices — in this case wages, benefits and flexibility — increase.

Economists have yet to reach a complete consensus on the causes of these shifts in worker supply and demand, but most agree that the COVID-19 pandemic played a large role in one way or another, whether through reopening hiring bursts, changing worker sentiments or stimulus incentives to stay home.

Many workers remain constrained by the pandemic and unable to come to work. Some are still worried about COVID, and others have children or other dependents to care for, Dziadula said, naming some of the circumstances that limit the labor supply.

“Kids are in quarantine. Schools are closed on and off. For people who have dependents, it’s been more difficult for them to return [to work],” she said.

Stalled immigration has also contributed to changing labor dynamics and decreased supply of workers, Dziadula added.

“Historically, a significant portion of agricultural and essential industrial jobs are taken up by immigrants,” she said. “If the flow of people stops, then the only way you can get people to work those jobs is to increase wages.”

Empty silverware holders, no late-night quesadillas: Notre Dame feels effects of nationwide labor shortage

Maggie Eastland | The Observer

North Dining Hall encourages students to join the staff, advertising base pay of more than $13 per hour.