A year of trial and error

Nov. 2, 1967 | Observer Staff | Researched by Lilyann Gardner

“With a Purpose and a Promise.” This phrase was coined at the inception of Notre Dame’s influential journalistic endeavor and was the drive behind bringing authentic and meaningful news to the community. One year later, the 1967 staff of The Observer reflected on the highs and lows of the paper’s first year, sharing their thoughts on what it takes to create a paper for the people.

The Observer published a special edition for its 20th anniversary, highlighting the reflections of The Observer’s founding fathers, who look back fondly at their contributions to student journalism at Notre Dame.

Silencing The Voice: One newspaper dies, another is born

Nov. 7, 1986 | Pat Collins | Researched by Evan McKenna

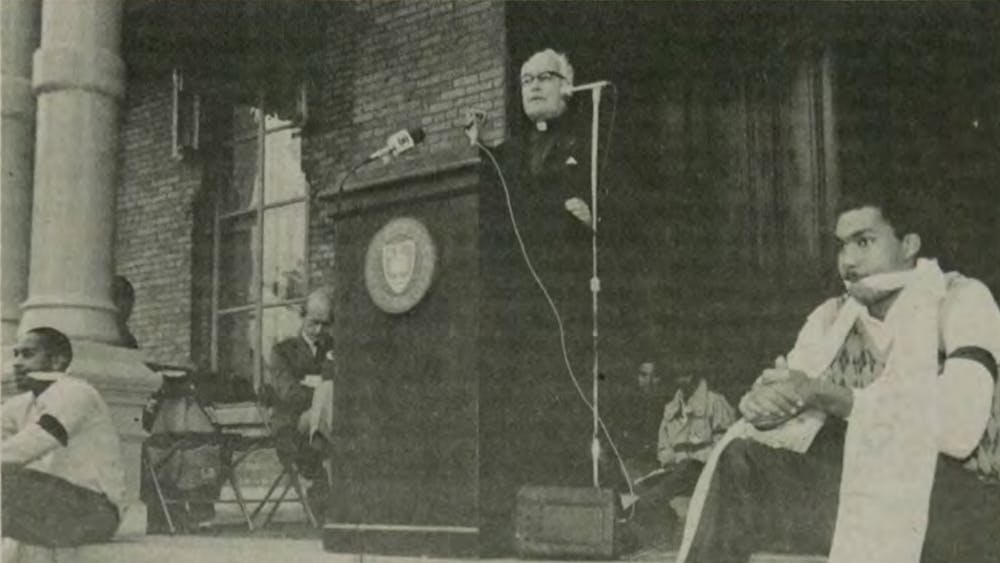

On Oct. 27, 1966, Notre Dame student newspaper The Voice pronounced itself dead — simply and plainly. “The voice is dead,” read the top of the front page in bold, black lettering. Less than two weeks later, the first issue of The Observer was disseminated across the University’s campus. Its front page contained a more hopeful headline: “A promise, a purpose, a newspaper is born.”The timing of these two events seems suspicious — and staffers from both The Voice and The Observer weren’t afraid to admit this. According to Steve Feldhaus, the editor-in-chief of The Voice at the time of its demise, the newspaper’s death wasn’t an accident; it was an intentional “euthanasia” in an attempt to start over and begin with a blank page.“Because we killed the product didn’t mean we were murdering the idea,” Feldhaus said, his words quoted in the first issue of The Observer. “There was a need for a news-oriented publication then, and there is now. We just went out and got it.”Although the men’s plan — shutting down The Voice in order to turn over a new journalistic leaf — was openly shared in the first few issues of The Observer, the specifics of its execution were never made clear. What exactly brought about the “untimely but rather expected demise” of The Voice? Who led the charge? And why was The Voice deemed unsalvageable? Two decades later, in The Observer’s 20th anniversary special edition, one of the hitmen involved in the takedown of The Voice spoke out on the scheme. As a high schooler, Pat Collins worked as a sports reporter for his local newspaper. But he didn’t want to be a journalist — and his father made sure of this. “Newspaper men,” his father constantly reminded him, were nothing but “glorified gossips.” He encouraged Collins to step away from journalism and become a doctor like him.So as Collins began his undergraduate career at Notre Dame, he heeded his father’s advice.“I took a solemn oath in front of God, and more importantly, my father,” Collins wrote. “The oath that I would leave newspapers behind me, go off to South Bend, enter pre-med and study as hard as I possibly could to become a physician.” But Collins couldn’t stay away for long. By the end of his freshman year, he had started his own short-lived publication, switched from pre-med into English and joined the staff of Scholastic. His father might have been disappointed, but he found great joy in writing and publishing “slick accounts of all kinds of activities in and around campus.” But there was another publication on campus, he noted: The Voice, a newspaper funded by the University and based primarily in student government. Collins wasn’t exactly a fan.“... it was an every now and again thing. It was stale, stodgy and usually late,” he wrote. “The Voice was financed by the University, but I think they spent more money on chin straps for the football team than they did for the newspaper.”So in 1966, Collins’ junior year, he teamed up with two seniors — Robert Sam Anson and Steve Feldhaus — and concocted a scheme: “a secret plan to take over the Voice, kill it, and come out with a brand new paper.”As the editor-in-chief of The Voice, Feldhaus had complete power over the inner mechanisms of the publication. With his help, the plan was executed easily, and The Voice of Notre Dame was no more. But why did these students go to such great lengths to end The Voice and establish The Observer? Their primary motivation was the hope of complete editorial freedom. While The Voice was funded by the University, The Observer would ideally operate independently, through the help of students’ subscription fees and advertisement purchases from the community. And this difference provided one large advantage, Collins noted: complete independence in deciding what gets printed.“Independence was a big thing then … it still is,” he wrote. “Because whoever controls the money you use to publish ultimately controls what you publish. We wanted to be free.” The Observer would go on to become the University’s longest-running independent student publication — but its inaugural set of staff didn’t know this yet. Slowly but surely, and with the help of dozens of budding student journalists, the paper found its footing. In a matter of months, the paper would establish itself as a significant force in campus media.“We recruited the best writers, the best salesmen … and we were off,” Collins wrote. “In about a year and a half’s time we went from an ‘Every so often newspaper’ to a daily, with students not only doing the writing and selling, but a lot of the production work as well.” And although The Observer was and still is entirely student-run, Collins emphasized the paper’s unyielding dedication to professionalism. “It was great fun, but it wasn’t a play newspaper,” Collins said. “It was a real newspaper reflecting the thoughts and attitudes of the students like never before.”Times were different 20 years ago

Nov 3. 1986 | Robert Sam Anson | Researched by Christopher Russo

One of The Observer’s editors-in-chief, Robert Sam Anson (‘67), provided a reflection on the early years of the paper 20 years after its inception. Anson presided over the campus transition from The Voice to The Observer. Although bankruptcy contributed to The Voice’s demise, Anson pointed out that the paper lacked sections that would later drive readership, such as opinion and sports.The first edition of The Observer was printed less than a week after the debut staff was pulled together. According to Anson, on Nov. 3, 1966, “the general reaction was shock. Here was a newspaper that was fact-filled, slick-looking, and rarest of all for Notre Dame, positively bristling with opinion.” From the “lunacy” of the Vietnam War to the “deplorable lack drugs, booze, and sex on campus,” Anson reminisced on the news landscape that existed during the 1960s and the blunt commentary that he published in The Observer. Much of the content of the Anson administration was controversial, to say the least. Unimaginable in a modern issue, early editions had the weekly “Observed” feature, which usually featured a Saint Mary’s girl in a pin-up costume. Despite admitting the “gross sexism” he allowed on the pages of The Observer, Anson claimed that “the tactic worked.” Their biggest controversy came when they filled a hole in the page with a reprint from the Berkeley Barb, which included a five-letter word for fornication that did not sit well with the University administration. The paper was required to issue an apology to the entire Notre Dame community. If they refused, the paper would be shut down and those responsible, including Anson, would be expelled. They ultimately wrote a letter of apology — “a most snottily artful one it was” — and the crisis was averted. Anson noted the variety of career pathways that have siphoned off Observer journalists, including law, business and the IRA. He hoped that the paper would continue to exude the same passion that he infused into it. After all, when he was at the helm, “week after week,” The Observer “demanded that you read it.” Though he yearned for the “hot-blooded journalism” of the 1960s, Anson also provided a salute to The Observer in its evolved form.“To my astonishment, and that of my ragtag collection of friends who were there those 20 years ago, it has continued, and, in continuing, become a far better and more professional paper than anything we could have ever dreamed of.”

The necessity of student newspapers: A reflection

Nov. 7, 1986 | Bill Dwyre | researched by Uyen Le

For the Observer’s 20th anniversary, Bill Dwyre (‘66), the founder of The Voice, reflected on the importance of student journalism in contributing to a campus culture. “To be a university is to have a student newspaper,” Dwyre started the article. “It is that simple.” At the time that Dwyre wrote this reflection, he was a sports editor for the Los Angeles Times. Writing for newspapers was one of his greatest passions, and that passion was cultivated for him at Notre Dame. During Dwyre’s college years, he noted, Notre Dame lacked a timely news service. “Notre Dame was a great vacuum for local news, campus doings,” Dwyre noted. “It wasn’t news until it was printed in the Scholastic, so sometimes, it wasn’t news until weeks later.” Admittedly motivated by the potential of campus fame and job prospects, Dwyre and some friends decided to start their own student newspaper, The Voice. Though they recognized that their first batch of papers needed plenty of improvement, they were proud to call it theirs. Dwyre commended The Observer for carrying on the legacy of The Voice, recognizing how far student journalism had come since his time at Notre Dame and how essential it is to a college campus. “What a university can’t flourish without is a pulse, a monitor, a voice or observer of itself,” Dwyre asserted. Introspection, for Dwyre, was the key for success. Student newspapers offer that inward look that is necessary for self-reflection and subsequently positive change. To have a place where students could express their views about campus happenings was what kept colleges alive, Dwyre argued. Student publications shape how the Notre Dame community understands and grapples with pressing issues. A strong student newspaper can be seen as a badge of pride for those who read it. “The students who put out the paper want it to be good so that the students who read it will be proud of it and cite it as a positive of their daily student life,” Dwyre reflected. In these last 45 years, The Observer has grown so much. Today, we publish daily, both in print and online. We hope that we have made the founders proud by fulfilling their vision of a publication that is for the students of Notre Dame, by the students of Notre Dame.