At the core of the human condition lies inescapable bias. Our secluded and invisible perspective on the world carries with it a very overt and visible indication of pre-judgment, conception and preference. Much of our life is defined not by the existence or non-existence of our biases but, rather, the shape they take.

In highly data-rich environments, institutions turn to analytics in an attempt to remove the commonly misconstrued “imperfections” that ride on the coat tails of biased thinking. A strictly human approach to the problems around us could lead to more questions than we find answers, so surely rigid objectivity ought to work around that disappointment, right? No.

Even the largest and most highly robust data sets, and the insights that we can extract from them, hold implicit bias in their structure and content. No golden data set exists, not even in private sectors.

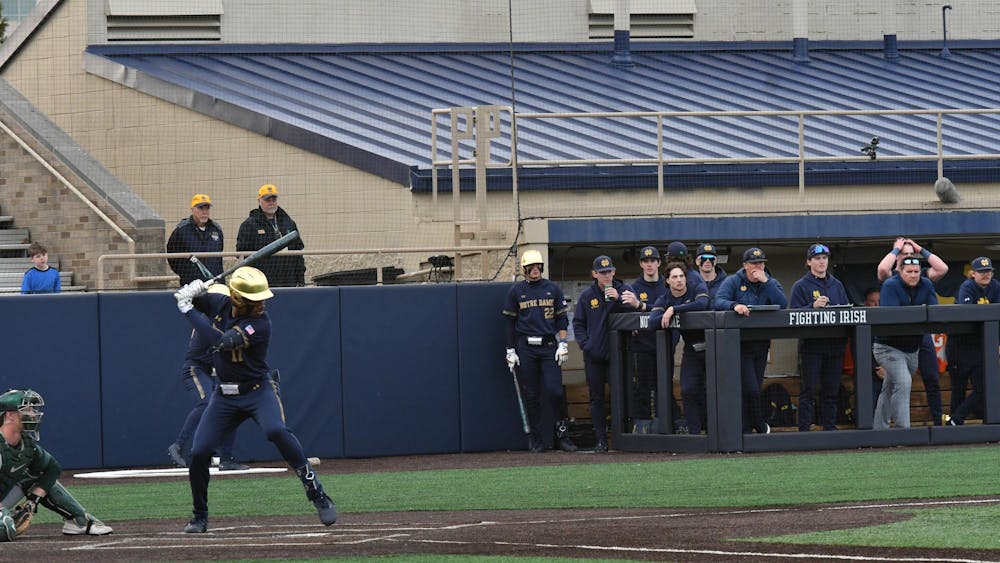

Take baseball’s modern era, for instance. The introduction of the live-ball era in 1920, where after a series of rule changes there was a massive influx in offense across Major League Baseball. This is due to the fact that previously the ball would almost never be replaced, and in addition, pitchers were able to deface and cut into the ball. Upon realizing the unprecedented advantages that power, contact and plate discipline would hold for the foreseeable future, the “five-tool” scouting archetype for valuable players was born. A predominance of competitive advantage would stem from extracting offensive value from players; an offensive focus would come on both the scouting and player development side.

But in spite of the new initiative to find and develop talented players that would be fit for the live-ball era, the bias of the project would be painfully unavoidable for data-focused front offices. With the aspects of a successful and “valuable” player changing so quickly, offices could not have responded to that shift without scouts to drive the value approach. Why? Past season data grew vastly outdated, unable to showcase the quantitative signs of value in the new era. Granted, sports front offices did not hold the computational power to build the complex algorithms and models that are commonplace today. Even if they did, the historic inputs would inevitably produce a poorly biased output.

All things considered, it is plain to see why by the 1960s, the depth and involvement of scouting in professional baseball soared to new heights.

Of course, the shift from dead-ball to live-ball baseball is an extreme case of contextual bias. The complications with extracting the right value inflated in concert with the speed of the game’s revolution. We simply haven’t seen something as momentous since. But at its core, the principle of contextual bias is knit into the very fabric of sports management; with a distinctly human game comes intangibles that technology is still far removed from measuring.

The fragile relationship between analytics and aesthetics, between the objective and the subjective, remains in constant flux. No matter how it changes as baseball matures, scouts will always play a pivotal role in the dynamic. Using subjective scouts to dilute bias in objective sports statistics may feel backwards. But humans have the agency to actively seek the intangibles, to ensure that the analytical insights match the appearances. Computers don’t meet parents, speak with coaches and detect deep-seated flaws that could be easily exposed and not easily fixed at the next level. Scouts do.

To quote Ken Rosenthal, “Analytics are an equalizer.” Balancing a human approach to talent searching with analytical methods should not compete with each other, nor are the two front office tools mutually exclusive. In sports, matching the insights of a black box with the reinforced observations of a scout invites an open line of communication that equalizes the present biases against the past ones.

So onward to equalize.

Read More

Trending