School officials react to potential merger

Nov. 27, 1967 | Nov. 16, 1970 | March 25, 1971 | Kevin McGill | Researched by Leah Perila

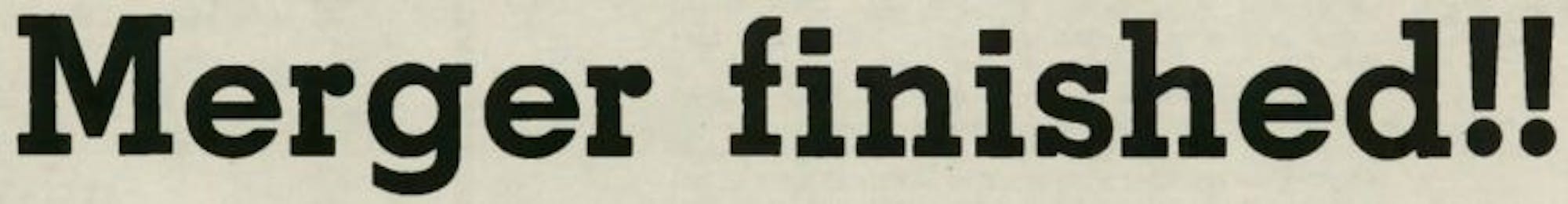

Perhaps unsurprisingly, debates over the merger between Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s proved contentious over the years.In 1967, Saint Mary’s abruptly fired its president, Sister Mary Grace, seemingly because she did not support the merger.Sister Grace said that religious superiors had expressed dissatisfaction to her with the progress of the merger, specifically implicating Notre Dame President Fr. Theodore Hesburgh.“I believe that I was relieved as president because of the wish of the board of religious trustees that a merger with Notre Dame proceed much more rapidly,” Sister Grace said.However, Fr. John J. McGrath, Sister Grace’s replacement, denied these accusations.“There has been no collusion over the abrupt removal of Sr. Mary Grace,” Fr. McGrath said. “I haven’t talked with anyone at Notre Dame and have never met Father Hesburgh.”

Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s students protest in favor of coeducation

Jan. 15, 1970 | Dec. 1, 1971 | De Ellis | Researched by Lilyann Gardner

The years leading up to the inauguration of the University of Notre Dame as a coeducational institution were filled with debates, protests and polls.A poll conducted at the start of the 1970 spring semester revealed that the overwhelming majority of Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s students supported coeducation. Notre Dame’s student body had an 84.1% approval rating for admitting women while 74.5% of the St. Mary’s students said that Notre Dame should admit them.However, the survey also revealed some of the concerns students had about the merger — 66.6% of Saint Mary’s students felt that if the merger went through, Saint Mary’s would lose its identity as a college.Several male students also said that they believed coeducation would be the downfall of Saint Mary’s because of the role Notre Dame plays in the institution's identity. One student went as far as stating that Saint Mary’s had no identity beyond its connection to Notre Dame.“What identity does St. Mary’s have other than being ‘the girl’s school next to Notre Dame?’” he asked.The discourse, though often discordant, was primarily in favor of a coeducational merger. But the students’ opinions were not enough to make the merger happen.Approximately two years after this poll, The Observer highlighted the frustration of many Saint Mary’s students when the merger fell through.On Nov. 30, 1971, 1,300 students, predominantly from Saint Mary's, agreed to boycott classes to protest the collapse of the merger.Sister Alma, the President of Saint Mary’s, held a convocation to discuss the fallout and was met by several disgruntled students.“What grounds do we have to place our trust in this college?” Saint Mary’s student government secretary Nancy Christopher asked.Sister Alma attempted to placate their vexation over being kept in the dark about the merger by encouraging the students to continue discussions with Notre Dame’s administration about transferring. This was not enough to satisfy the students.Freshmen were particularly disappointed with Sister Alma’s lackluster suggestion. Many of them applied to Saint Mary’s under the belief that they would eventually receive a Notre Dame degree.Alma shamed the freshmen and protested that Saint Mary’s had never advertised that sentiment, despite press releases from the College saying otherwise.“I wonder if it would not be a good thing for the majority of freshmen to return,” Sister Alma professed.Alma’s disregard and disrespect of her students’ perspective led Saint Mary’s student body president Kathy Barlow to begin a boycott at Saint Mary’s before traveling down the road to garner support and numbers from the men of Notre Dame.Notre Dame student body president John Barkett (‘72) emphasized that he did not think Notre Dame students would be as passionate about the failed merger and the boycott since it did not impact them as strongly. But Barkett suggested that Saint Mary’s students should continue to pressure the Board of Trustees.“I hope that most students at Notre Dame will act as they see fit,” Barkett said. “St. Mary’s students have a legitimate complaint.”The boycott did little to rectify the breakdown of the merger, which will be covered next. But the desire for coeducation was heard loud and clear. These prevailing sentiments seem to foreshadow the eventual introduction of women into the Notre Dame community in the fall semester of 1972.Notre Dame-Saint Mary’s merger is terminated amid accusations and rumors

Feb. 29, 1972 | Ann Therese Darin | Researched by Adriana Perez

Accusations, rumors, resignations and more: after almost a year, negotiations between Notre Dame and Saint Mary’s came to a head at the end of February 1972, when College trustee and chairman of the coeducation committee Fr. Neil McCluskey announced that the merger would not occur.“The officers of the Sisters’ Congregation have usurped the authority of the Board of Trustees and administration,” McCluskey said. “Their decision, ignoring the mandate of the students, the faculty, the parents, and the Board, is no merger.”He also announced his resignation from the Board of Trustees. “I feel my input is terminated,” he said. “I see no future for St. Mary’s without Notre Dame.”