Whenever somebody cooks in our shared thirteen-person kitchen, the smell of sauteing onions puts hooks into the unsuspecting person and draws them toward the stove. No matter how dissatisfying the meal might end up, that fragrance — paired with the interruption of a housemate peeking into the kitchen to say how delicious it smells — is enough to keep one going.

Of course, in the biological sense, you don’t need onions (or their aroma) to survive. We need food, yes, but the bare minimum of nutrition doesn’t necessarily require flavor. You can eatunseasoned chicken breast and quinoa for a long time and keep doing what it is you need to do. And yet, for some reason, many of us have an interminable desire for flavor, for food to be scintillating and beguiling and for our plates and palates to be danced upon.

Food is love, just as it is art. Food is love whether you are sitting at a cajun restaurant in front of a plastic bag of shrimp and looking across the table to see that the spice is making your father sweat even more than you or when your mother puts a few drops of curry in your mouth to see if the amount of salt is right. The look in a friend’s eyes as they accept your recommendation of the shrimp rigatoni at The Lauber and the restless anticipation in the boom boom salad line.

When I opt to skip dinner rather than eat the free meal I’m presented with before class in Dublin, refusing to take the soggy cardboard box with my name on it, smelling of something indiscernible. It feels wrong to be so “picky,” as I remember all the children I have known who did not have the choice to refuse the food they were blessed with. But my upbringing spoiled me deeply, making those late-in-the-semester treks to the dining hall so painful, as I seek to prepare my tastebuds for a shower of mediocrity.

Food — flavor, fragrance, family and maybe some other f-words — has always been one of the most important things in my life. When I smell onions frying and feel my mouth begin to water, I am transported to the places I grew up, where the aroma would waft through the halls and into each and every room. More often than not, the onions would soon be introduced to ginger and garlic paste and spices from my mother’s stainless steel “masala dabba.” The smell was an invitation to saunter down to the kitchen and watch my mother’s art take shape on the stovetop, almost levitating off the ground like Mickey Mouse towards the steaming pie on the windowsill.

I remember my cousins and I made fun of our parents for exclusively going to eat at Indian restaurants on the sparse occasions we went out to eat, but how could they not? For one, once you’ve had the best, you can forget the rest. But on another level, those flavors are impossible to leave behind once they are inextricably tied to the love you have felt through them. I can’t forget the feeling of my mother hand feeding us soft khichdi with squash or eggplant or shrimp or a hundred other dishes — long after we were capable of feeding ourselves.

I myself have ended up in London over and over this year, chasing the thrill of Indian curry shops and takeaways, becoming my parents by recalling the kitchen of my childhood. In that kitchen, the labor my mother put into her food may have been exhausting and intensive, but it was never dissatisfied or devoid of love. As she filled to-go containers with chicken legs and pasta to fill the trunk of the car and offer a bite and smile to the homeless, there was no question that this was what food was for.

On a visit to my friend Liam in London, our conversations kept returning to this idea. I sat at his dorm kitchen table as he made burritos with halal chicken he had bought just for me. We had walked around South London, trying Jamaican saltfish and beef-and-cheese patties and sipping Ethiopian coffee while taking in the Afro-Caribbean rhythms of Brixton. We walked around Tooting, sharing one flavor after the next from my childhood; the milky richness of Indian sweets and the inexplicable nature of pani puri — a street food consisting of a fried sphere filled with spicy water — immediately thrown into one’s mouth to burst like a water balloon.

We sat in the King’s Cross Dishoom eating lentils as Liam’s eyes opened wide at the force of these simple legumes. Cheap, filling and rich in all the important things, dal is central to so many Indian cuisines for a reason. The people who come from my ancestral village still largely practice the Friday tradition of cooking dal — often followed by a contented nap.

A friend of my mother’s once wrote in reflection on a night when my mom had, as always, “cook[ed] enough to feed everyone in that building because that is what she does.” As Tiffany wrote, my mother was “an incredible cook and manager of resources and she can feed hundreds for less than most of us spend to feed our family.” That budgeting was real, and dal was one of those secrets. But there was something far more priceless in her food: the flavors of love.

Finding flavortown

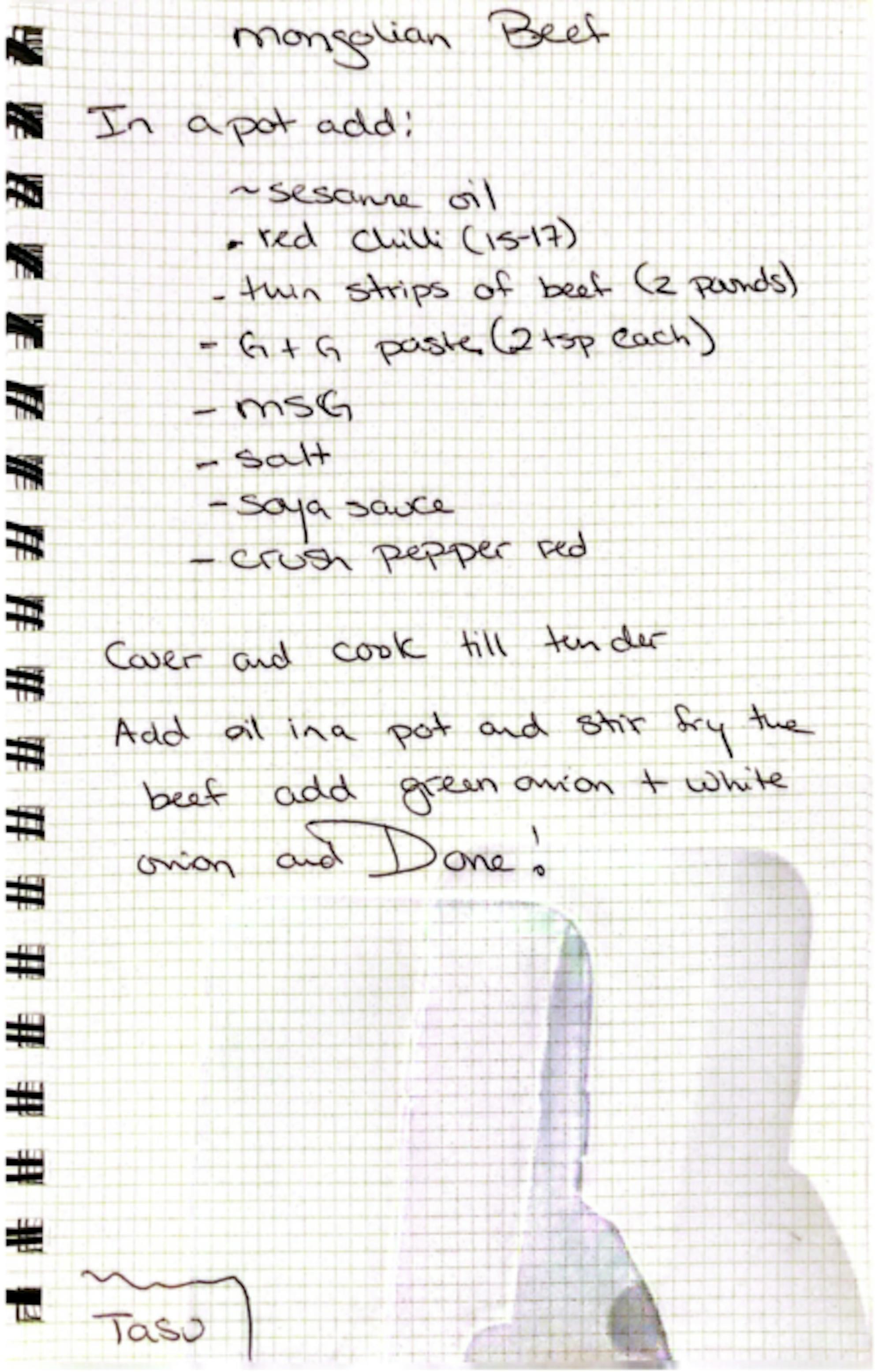

A recipe for Mongolian beef from the author’s mother’s recipe book.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Observer.