During an expedition to his second plantation on the other side of the island, Robinson Crusoe stumbles upon a human footprint on the sand. Instead of rejoicing on the possibility of company or salvation, his first instinct was to retreat to his fort in fear of savages and cannibals. As I read through this passage, I couldn’t help but relate to his desire to hide inside and refuse to leave the premises of his “castle” for years. Specifically, I understood his fear of what others could do to harm him and all that he worked so hard to build and grow. This constant fear and anxiety is extremely familiar to me or any other Brazilian. However, while Robinson had no real reason to be afraid, Brazilians have many reasons to be afraid everyday, especially due to the persistent economic and political turmoil Brazil faces.

One of my earliest memories as a child is seeing my parents leave for work in the morning and going to bed before they came back. Every time I asked them why they worked so much, they always said “A gente tem que aproveitar o máximo que dá hoje, porque amanhã a gente não sabe o que vai acontecer” (We have to make the most of today because we don’t know what will happen tomorrow). That never made sense to me. Why would they think so much could change in one night? As I matured and learned more about my country’s history, I came to understand why they felt so uneasy about what tomorrow would bring.

In a country like mine, whose governmental intuitions are weak, the political and economic status quo can change in the blink of an eye. For example, in the Military Revolution of 1964, within just two days the president was deposed and exiled. That short revolution began a decade long military dictatorship. My grandmother tells me a lot about this dark period in Brazilian history: inflation was as high as 84% per month and stores changed the prices of all products at least twice a day. Even after the dictatorship ended, we were very far from being stable. During the first week of the new democratic government led by Fernando Collor, 80% of all money invested in banks was with held by the government with no previous notice. Even 30 years after the incident, some people still haven’t gotten their money back. As a response to this traumatic history, Brazilians became a sort of superpower Lockean figure. Akin to Robison Crusoe after he got to the island, we are extremely productive and feel like we constantly need additional income, even if we have well paying jobs.

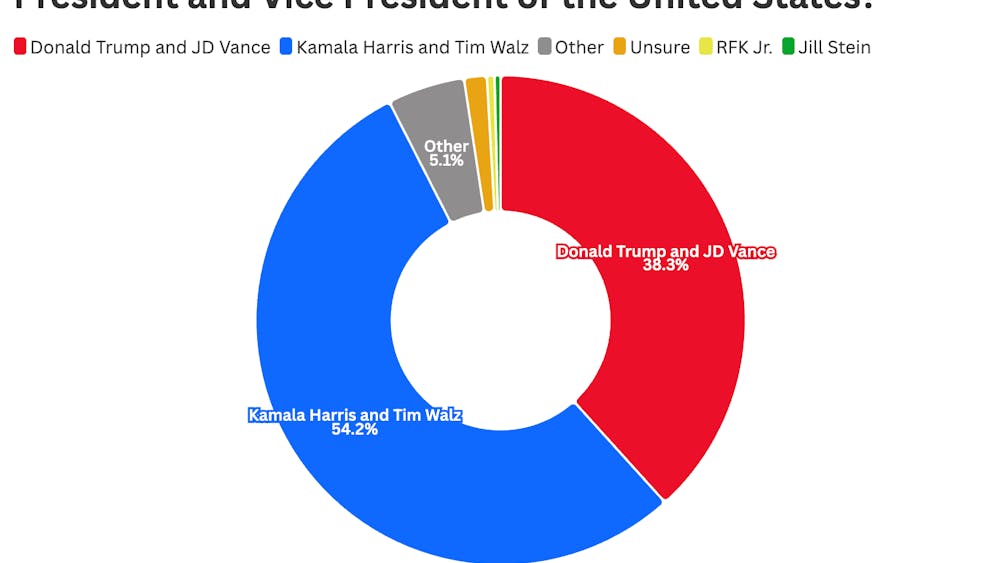

Last year, we had the Brazilian presidential elections. All of the Brazilian students in Notre Dame were extremely apprehensive about the results and spent the whole day checking how the vote count was going. Most of my American friends who saw us tirelessly refresh the government page were extremely puzzled by it. They didn’t understand why it mattered so much to us given that most of them didn’t even know when elections in the U.S. would happen again, who they would vote for and even if they were going to vote at all. That got me wondering why our political and economic status quo are fundamentally different, why we worry so much while most Americans don’t feel like politics affect their daily lives. To these questions, I came to the conclusion that from the beginning we have been fundamentally different.

English colonial settlements in America like the Province of Carolina were ruled by fundamental constitutions proposed by proprietors which in Carolina’s case included the Earl of Shaftesbury. Along with that, the settlement’s righteousness was defended by prominent philosophers such as John Locke who was at the time one of Shaftesbury’s secretaries. The concepts developed in Locke’s “Second Treatise of Government” were used to justify England’s right to American soil. This was based on the idea that Native Americans were living in a state of nature and did not exploit the land properly and therefore had no property rights over the land, as opposed to Englishmen who exploited their new estate to its fullest and, as a consequence, had this right to property.

In contrast, most proprietors of Brazilian settlements in the early colonial years never claimed their lands, let alone established a constitution with philosophical support. For most of that period, Brazil was used as a sugar plantation, wood extraction site and a way for the Catholic Church to expand its reach through the missionary education of natives Brazilians. Portugal only began to formally colonize Brazil when other nations started to invade northern regions such as Recife and Olinda. Instead of being reinvested in Brazil, the profit made out of the exploitation of Brazilian resources was used to pay the crown’s debt to the English government. Along with that, most government decisions about Brazil were made in Portugal. As a consequence, Brazil did not receive enough investment and had weak governmental structures from the very beginning. These core differences in the founding of both nations unfolded into bigger and more prominent gaps as time went by.

As the years go by and elections happen, we must decide if we want to continue to relate to Robison Crusoe after stumbling on the footprint or start to trace our long way towards becoming an economic and politically stable nation whose people don’t have the need to act as super power Lockean figures in search of greater power and property.

Lara is a member of the class of 2026 from Taubaté, Brazil with majors in economics and Chinese. When she is not complaining about the weather, you can find her studying in a random room of O'Shaughnessy with her friends or spending all her flex points in Garbanzo. You can contact Lara by email at lvictor@nd.edu.

The views expressed in this column are those of the author and not necessarily those of The Observer.