“You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backwards,” Steve Jobs once said. “So you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something — your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.”

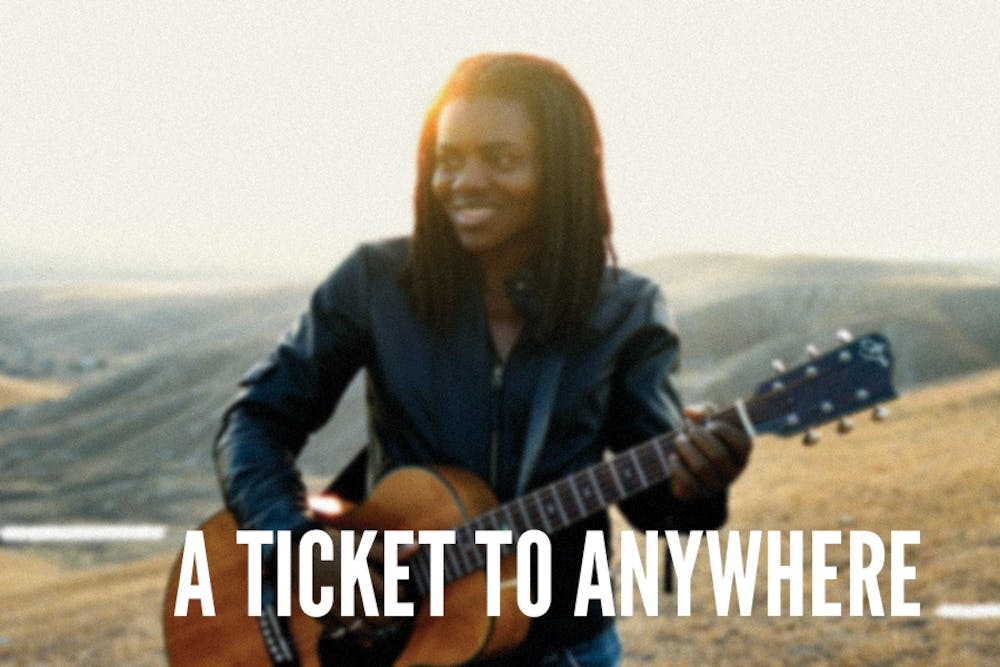

So much of life is up to chance, and singer-songwriter Tracy Chapman’s rise to fame is no different.

As a college student at Tufts on scholarship, she busked in coffee shops, Harvard Square and Boston’s subway stations. That is, until Brian Koppelman, another Tufts student with connections to the music industry, heard her music and convinced his father to help her sign with Elektra records.

After a modest release of her self-titled debut, Chapman was invited to play at Nelson Mandela’s 70th Birthday Celebration at Wembeley Stadium in London. Chapman performed earlier in the day, but she was brought back on stage after Stevie Wonder experienced technical difficulties. Somebody saw Chapman hovering around backstage, put a guitar in her hands — and she stunned an audience of nearly 75,000 into complete silence.

“Fast Car” is the kind of song to do that sort of thing. Even though Chapman wrote the song at 24, the song has the wisdom of somebody much older and wiser. It’s steeped in American imagery and ideology. It creates a world of endless highways with infinite possibilities and a deep belief that hard work will get you somewhere. The fast car Chapman sings about offers her mobility through space — but also upwards towards a higher class. All that infinite potential and hope is part of being young. For Chapman, growing up is about letting all that go.

Two weeks after her performance, her album sold 2 million copies. Chapman became an overnight sensation.

If Chapman never got her scholarship, if Koppelman never listened or if Stevie Wonder didn’t forget his synthesizer at home, “Fast Car” might have never happened. Chapman’s talent is undeniable, but she owes part of her success to a complicated Rube Goldberg machine of fate.

“I always considered trying to make a living playing music,” Tracy Chapman said in an 1988 interview with Rolling Stone. “But it was always really clear to me, at the various stages in my life, that it really wasn’t a possibility unless some phenomenal thing happened.” And it did.

But you’re only famous until you aren’t anymore. Chapman’s hesitation to make public appearances led her to fade from the public eye. That is, until 2023, when country musician Luke Combs covered “Fast Car,” which subsequently exposed the song to a new audience and revived interest in the single. Chapman later became the first Black woman to win Song of the Year at the Country Music Awards.

This week, Beyoncé became the first Black woman to top the Billboard country chart with “Texas Hold ‘Em.” Her other single “16 Carriages” is more lyrically impactful. “16 carriages drivin’ away / While I watch them ride with my fears away,” she sings. “Had to sacrifice and leave my fears behind / The legacy is the last thing I do / You’ll remember me ‘cause we got somethin’ to prove.”

If the revival of “Fast Car” and Beyoncé’s pivot into country music indicate anything, it’s that Black and white country music fans have more in common than they think. We all dream up fast cars and carriages to take us away into a brighter future.

Country music should reflect our country. It should be — and is — for everyone.