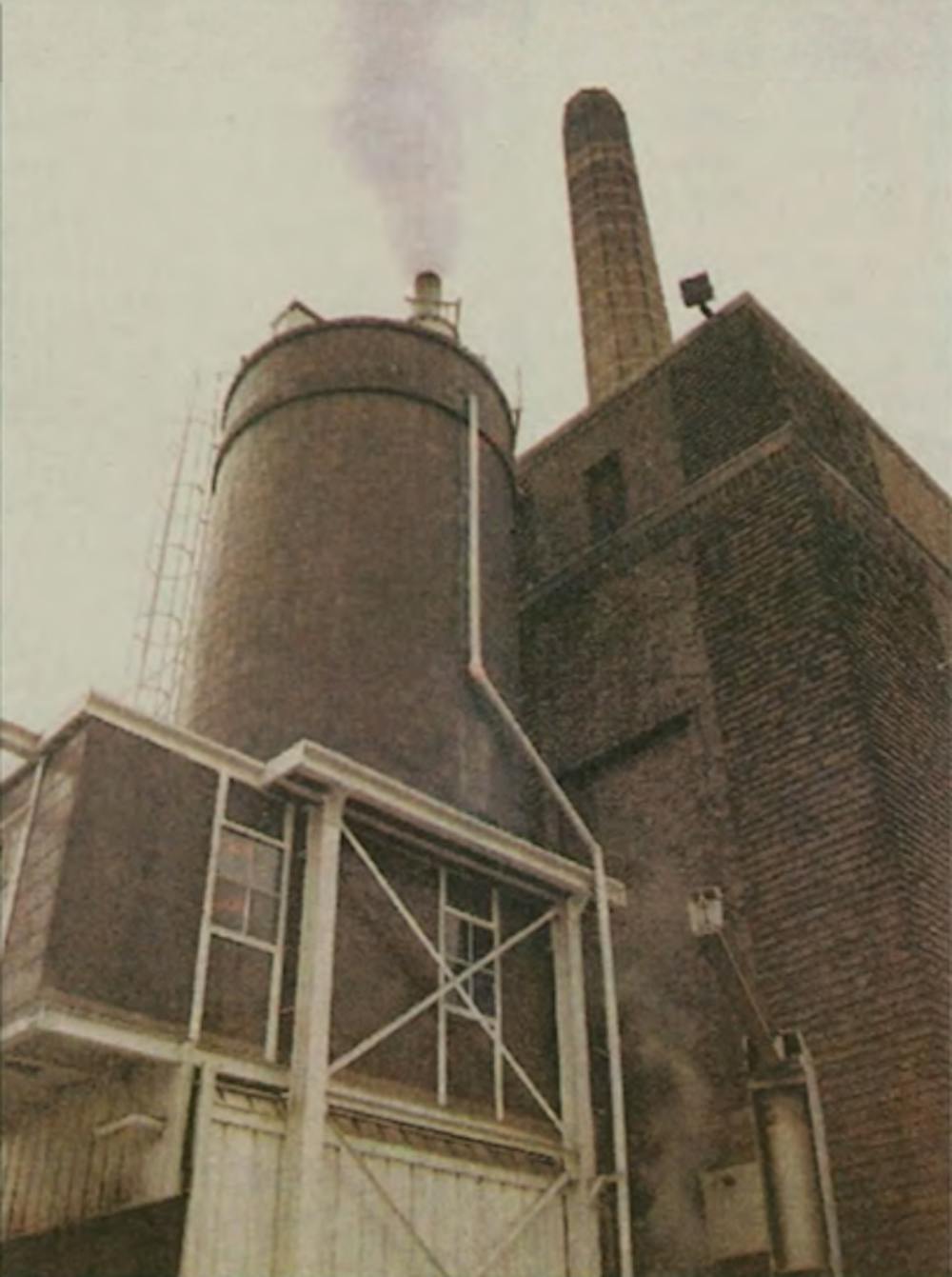

First built in 1932, Notre Dame’s on-campus power plant illustrates an ongoing journey from an era of energy crisis to its present-day commitment to sustainability. Initially caught unprepared during the 1970s energy crisis, the University’s early inaction and the subsequent scramble for policy formulation set the stage for a broader narrative of adaptation and change. This storyline unfolds with a pivotal moment in 1999, when an explosion at the campus power plant not only caused significant damage but also sparked a reevaluation of energy practices and infrastructure. Further complicating the narrative, Notre Dame’s encounters with the EPA over violations related to the Clean Air Act underscored the challenges of aligning University operations with environmental regulations. Each of these episodes — from policy inertia and infrastructural crises to regulatory challenges — paints a vivid picture of Notre Dame’s path toward embracing renewable energy sources and implementing sustainable practices, highlighting its progress from reactive measures to a proactive embrace of a greener future.

Energy Crises to Sustainability: ND’s Increasingly Obsolescent Power Plant

Nov. 16, 1973 | Melissa Byrne | Nov. 14, 1974 | Paul Young | March 23, 2004 | Joe Trombello | Researched by Thomas Dobbs

During the energy crisis of the 1970s, Notre Dame found itself unprepared with a formal policy for energy conservation. Then-Assistant Vice President for Business Affairs, Brother Kieran Ryan, underscored the University’s early state of inaction with his remark, “The University has not yet formulated a policy concerning the conservation of energy on the Notre Dame campus.”

Waiting periods for updated guidance reflects the broader uncertainty of the 1970s oil crisis, with institutions grappling to respond to the new reality of energy scarcity.

The University’s power plant, capable of burning coal, oil and gas, with coal as the primary source, became a focal point in discussions of energy use. Chief engineer William Ganser provided insight into the looming challenges and the critical need for conservation, noting, “We anticipate the situation will grow worse.” He emphasized that effective conservation must originate from the consumer end — students, faculty and administration alike, underscoring a community-driven approach to energy savings.

The 1974 coal strike further tested Notre Dame’s resilience and preparedness. Ganser again assured the community of the University’s strategic coal reserves: “The Notre Dame power plant has enough coal stockpiled to heat the campus for almost four months, if it is a mild winter.” This stockpile was a testament to Notre Dame’s foresight in the face of potential energy shortages, demonstrating a blend of optimism and pragmatism.

A significant evolution in Notre Dame’s approach to energy conservation was evident in an 2004 energy-saving contest between dorms. Highlighting the initiative’s success, Virginia Kelly pointed out, “Welsh Family Hall reduced their total energy output by 8,310 kilowatt-hours ... This was enough to secure the dorm first place and a $100 cash prize.” This contest illustrated the potential of collective action in reducing energy consumption, showcasing the importance of awareness and simple, yet effective measures to decrease energy use.

These episodes in Notre Dame’s history underscore the evolution from an initial absence of an energy conservation policy to a proactive stance on sustainability. The University’s discontinuation of coal use in October 2019 illustrates its ongoing dedication to renewable resources. Particularly keen observers will spot the ongoing construction of a geothermal facility adjacent to the Joyce Center.

The 1999 Explosion that Shook Notre Dame

April 15, 1999 | Tim Logan and Robert Pazornik | April 27, 1999 | Observer Staff Report | Aug. 21, 1999 | Observer Staff Report | Researched by Lilyann Gardner

Campus residents nearest to the University’s power plant were awoken in the early hours of April 15, 1999 after the second largest fire in campus history led to an explosion in one of the plant’s northern cooling towers.

After raging from 12:58 a.m. to 2:25 a.m., the blaze was eventually extinguished through the joint effort of the Notre Dame and South Bend Fire Departments. Paul Kempf, chief electrical engineer, and Jami Thibodeaux, the on-call security guard, were both injured and transported to the local hospital with serious but non-life threatening injuries.

The frightened students fled from their beds to investigate into the incident themselves, lining the bank of St. Joseph’s Lake, but Notre Dame and South Bend Police forced them back due to safety concerns.

In an interview with the Observer, former Zahm Hall president James Moravek ‘00 and witness to the fire shared his initial thoughts during the ordeal.

“Our immediate concern was that something in our residence hall had exploded,” said Moravek. “We just decided the best thing we could do would be to come out here to see if we could lend some assistance to University officials.”

There was ultimately nothing that could be done in the days succeeding the explosion, and by April 27, the Indiana State Fire Marshal’s investigation was unable to determine the cause but had estimated the cost of repairs as totaling $1.35 million.

The majority of the damage affected six of the nine water cooling units, thereby disrupting air conditioning throughout the campus.

The University eventually restored air conditioning in the fall semester by spending $700,000 to rent cooling towers that would run between 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., only intended as a temporary fix for the residence halls until the towers could be fully replaced for the spring semester of 2000.

Notre Dame at Odds with the EPA

Feb. 16, 1996 | Liz Foran | Jan. 14, 1998 | Heather Cocks | May 4, 2011 | Megan Doyle | 2019 | ND Stories | Sept. 12, 2022 | ND Stories | Researched by Cade Czarnecki

The power plant on campus became more than just an eyesore when the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued a citation to Notre Dame in January 1996 for violating the Clean Air Act of 1990. According to the citation, Notre Dame exceeded the allowable limit of expelled particulate matter (fly ash, smoke, dust) and sulfur dioxide in the operations of its power plant.

Specifically, three of four coal boilers were to blame. Boilers provided the steam and electricity that powered the campus. Yet, when tested on seven separate occasions between 1991 and 1995, they were found noncompliant with federal law. In fact, it was calculated that if all four boilers ran at maximum capacity for an entire year, they would exceed the EPA’s limit for particulate matter by 400 tons and exceed the limit for sulfur dioxide by 500 tons.

By 1998, the EPA issued a $250,000 fine against the University related to the 1996 citation. The amount was paid for out of the University’s “general operations budget.” Signaling the end of EPA’s investigation of the University power plant, the University responded to the fine with a statement acknowledging that the boilers in question had been fixed in September 1996.

Notre Dame again found itself at odds with the EPA in a 2011 congressional hearing by the Subcommittee on Energy and Power. In a review of newly proposed EPA rules, Notre Dame’s Director of Utilities, Paul Kempf, testified that the EPA had not properly justified these new, stricter rules and noted the high cost of bringing the University into compliance. Additionally, he shared that the University had already spent $20 million improving the efficiency of the power plant to comply with new regulations promulgated in 2004.