Movies, paintings and music hold the unique ability to create conversation surrounding a wide variety of topics. Whether that is food, fashion or social justice, art alone allows people to easily approach a new topic, engage with it and develop a deeper understanding and appreciation for the subject. In terms of social change, art is a powerful tool for curating productive conversations around sensitive topics involving injustice and inequality. Not only does art contribute to the existing discourse of social justice, but it invites people to join the conversation. While this powerful tool has been used in social movements, activist circles and even politics, it is essential that we critically interrogate what art is being included in the discourse of the larger art world and what art is being left out of the conversation. Art is powerful, but if only specific artists’ voices are being represented in museums, how can we cultivate a diverse multifaceted cultural discourse surrounding art as a means for social change? An anonymous activist group in the 1980s called “the Guerrilla Girls” had this very same question, and they tackled it through the creation of provocative artwork which aimed to confront the sexism and racism within the art world and which effectively captured the attention of the art community.

My infatuation with the Guerrilla Girls began in high school when I took a class called “Artist as Activist” my senior year. In this class, we learned about the impact radical artists were having in fighting against social injustice. The Guerrilla Girls stuck with me, not only because they were a punk radical feminist group but because they were questioning the entire composition of the art world by asking whose perspectives are seen and whose voices get heard. I have always thought of art as a powerful social justice tool for challenging the daunting unjust hierarchical composition of society, but I had never considered that the art world itself was biased, exclusionary and lacking in diverse perspectives. Art is infinite, yet its exposure is limited by the same structures it is attempting to challenge. The lack of diverse artist representation in galleries shows how even a discourse which is framed as unlimited is deeply affected by the oppressive composition of our society.

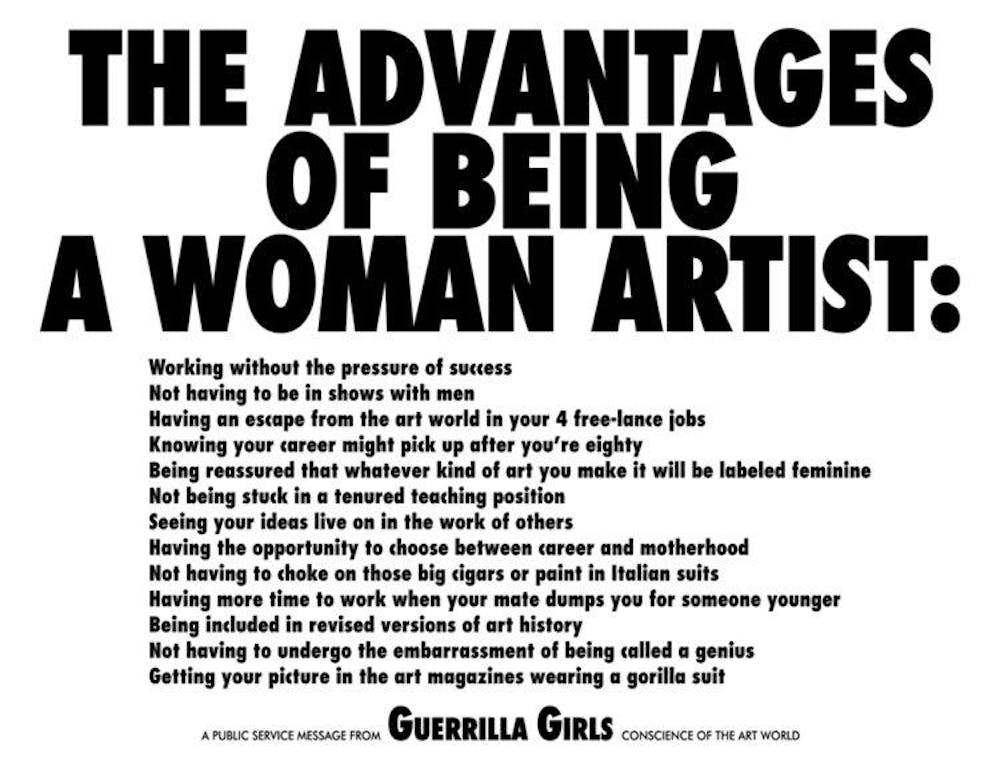

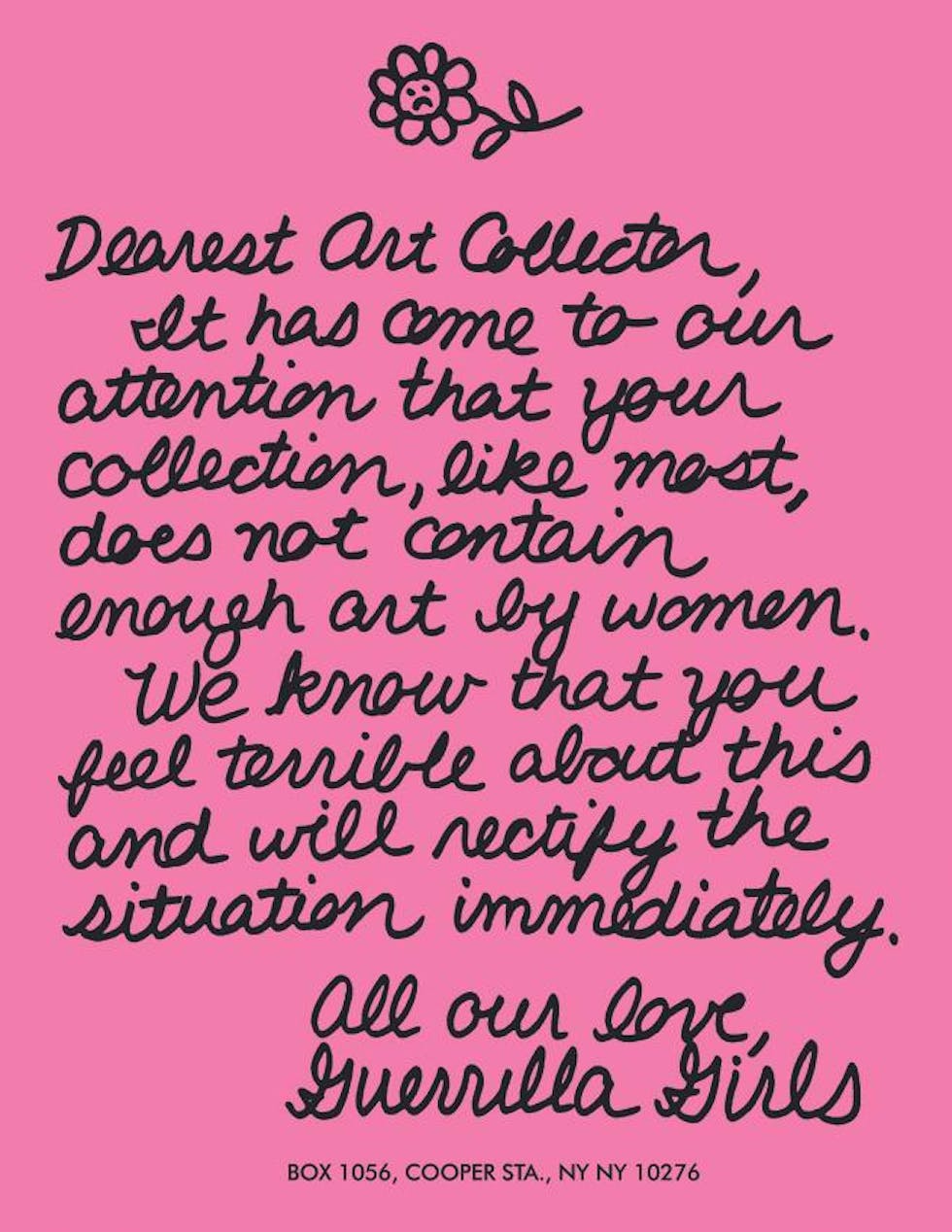

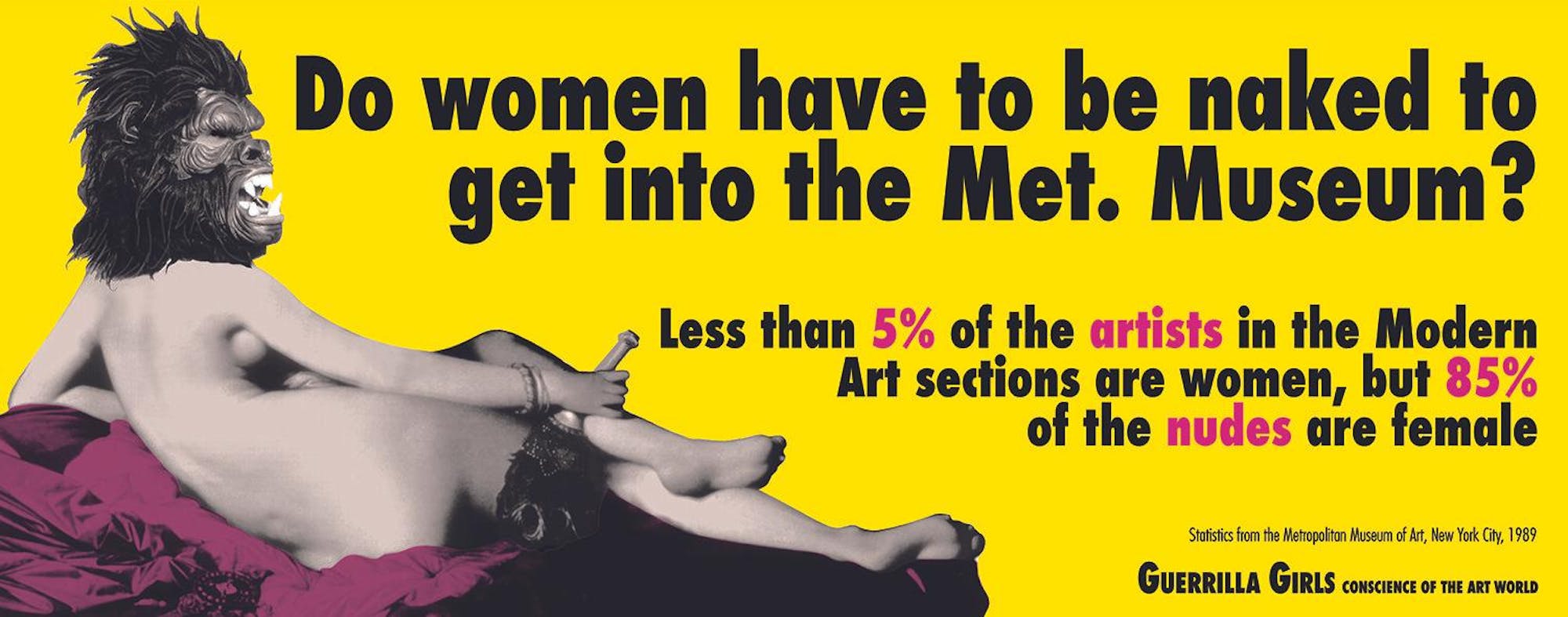

The goal of the Guerrilla Girls was to challenge the lack of representation along with the sexist and racist discrimination women face within the art world. They used the word “guerrilla” to embody the style of undercover street art while simultaneously playing on this word by using gorilla masks to hide their identities. As emphasized in this article summarizing the influential work of the Guerrilla Girls, it was important to the group that their identities were kept anonymous as they felt this allowed their audience to focus their attention on the politics of their activism rather than their own artistic identities. The Guerrilla Girls created a series of political posters that directly confronted the lack of diversity in artists represented at museums through a humorous idiom that captured the attention of a wide audience. They plastered these posters outside of art museums, art collections and in the artistic districts of New York City. The Guerrilla Girl’s work gained a large following, and their critiques of the art world were being heard. Their work ranged from posters with specific statistics surrounding artists’ representation within museums to provocative questions that effectively communicated their message. Among their most famous works — a poster which reads “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?” — communicates the reality of female artistic representation in museums. As stated on the poster, “less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 85% of the nudes are female.” Women artists exist, but the structural exclusion of their bodies of work prevents their perspectives from being seen and their artistic voices heard.

During my freshman year of college, I visited my best friend who was studying abroad in London where we went to see artwork in Tate Modern. To my surprise, there was an entire exhibit dedicated to the political artwork of the Guerrilla Girls. This emotional face-on encounter with the work of a feminist activist group I had studied and looked up to was overwhelming, and the fact that I was viewing their work in an art gallery was profound in itself. The existence of the Guerrilla Girls, their artwork and their exhibit is evidence of the revolutionary impact art can have in provoking social change. We must work to effectively interrogate whose perspectives are being represented in the discourse of art and how the rhetoric within that discourse is being framed. Women artists exist, artists of color exist, women artists of color exist, but their work is excluded from the collections within the art world. Diverse perspectives matter — they remind us we must make a conscious effort to confront inequality and injustice by challenging the mainstream exclusionary narratives within our society. Change is not easy: It takes time and effort. Art makes people feel, see and hear different perspectives of the world. It allows us to open our minds, shift our worldviews and grow our perspectives to transparently encounter the systemic forces which construct social injustice within our society. By using art to confront the very truth it delivers, we can work toward cultivating a society which listens to everyone’s voice as a way to implement a strong sense of community that celebrates our diverse human experiences.

Grace Sullivan is a sophomore at Notre Dame studying global affairs with minors in gender and peace studies. In her column I.M.P.A.C.T. (Intersectionality Makes Political Activist Change Transpire), she is passionate about looking at global social justice issues through an intersectional feminist lens. Outside of The Observer, she enjoys hiking, painting and being a plant mom. She can be reached at gsulli22@nd.edu.