The fervor for divestment at universities such as Notre Dame has historically sparked pivotal debates about the role of academic institutions in global ethical issues. This fervor is once again at the forefront as contemporary student movements call for the divestment from fossil fuels, echoing one of the largest and most coordinated divestment campaigns in history — against apartheid South Africa. Just as past students rallied against the moral contradictions of investing in apartheid, today’s advocates argue against supporting industries contributing to environmental degradation. In this two-week series, we first explore the South Africa divestment movement at Notre Dame, drawing clear parallels between past and present. We underscore the ongoing quest to align institutional investments with ethical convictions.

Divestment and Dissent

Nov. 2, 1978 | Kevin P. Ceary | Dec. 7, 1978 | Terri Walsh | Feb. 11, 1988 | Matthew Cleary and Patrick Kusek | Feb. 21, 1990 | Michael Allen | Researched by Thomas Dobbs

In the first student opinion piece in the Observer on divestment in South Africa, Kevin P. Ceary ‘81 sharply criticized Notre Dame's reluctance to divest from apartheid South Africa. He expressed strong disapproval of the University's stance, writing, “Because Notre Dame is an institution nurtured with a Christian tradition, one would expect Notre Dame to pioneer the withdrawal of investments from a corrupt society,” highlighting his profound disappointment in the University’s ethical inconsistency.

Terri Walsh ‘91 sharpened her criticism by focusing on the economic exploitation at the core of South Africa’s success, which heavily relied on an oppressed black labor force. She advocated for a reevaluation of Notre Dame’s investment policies to consider more than just financial gains, stating, “The economy of the Republic of South Africa is undeniably a very successful one. It is also undeniable that its success rate is directly attributable to the black labor force in South Africa.”

In contrast, a 1988 opinion challenged the effectiveness of divestment, suggesting that it would not significantly impact the South African government and could even worsen conditions for the black population.

Matthew Cleary ‘91 and Patrick Kusek ‘91 argued for strategic engagement rather than withdrawal. They proposed, “Instead of divestment, America should invest in South Africa. If America’s trade grew to the point at which South Africa depended upon our goods, then we could pressure them in much the same way that OPEC ran an oil embargo against the United States,” advocating for maintaining economic ties to encourage change.

In 1990, Michael Allen offered a pragmatic perspective on the U.S. presence in South Africa. He suggested that U.S. companies should not divest because doing so “would lose any direct chance of making life better for blacks in South Africa because it would lack the foundation from which to launch any kind of initiative.” Allen maintained that retaining investments could provide leverage for improving conditions and influencing policy within the country.

Students protest in favor of divestment

Oct. 14, 1985 | Mark Pankowski | Nov. 12, 1985 | Theresa A. Guarino | April 17, 1989 | John Zaller | Researched by Lilyann Gardner

Throughout the 1980s, Notre Dame students, in conjunction with the Anti-Apartheid Network, set out to challenge the University’s administration by calling for an immediate divestment from U.S. companies doing business in South Africa during the previously ongoing apartheid.

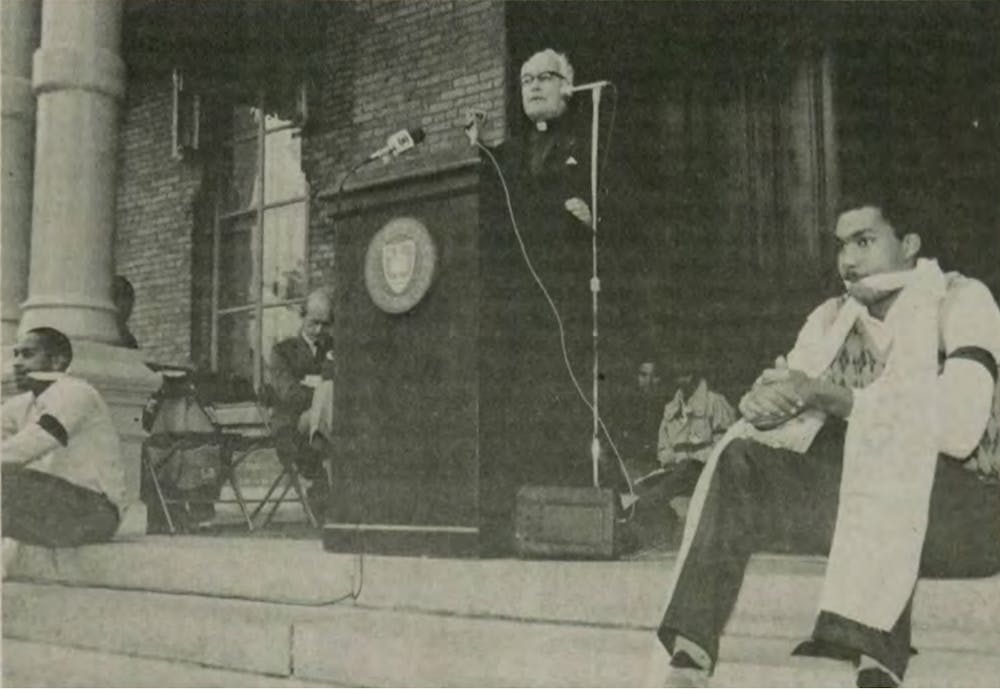

On October 14, 1985, as part of National Anti-Apartheid Protest Day, over 400 students organized the largest rally at the Administration Building. They wore black armbands, held signs and chanted “Divest Now” to protest against the inaction of University President Father Theodore Hesburgh and the financial decisions of the Board of Trustees.

Although the chants did not interrupt Fr. Hesburgh’s speech at the rally, he declared that total divestment would not be possible. He announced that the Ad Hoc Committee on South African Investments would prepare a statement to present to the Board in the coming weeks.

Fr. Hesburgh and then-student body president Bill Healy '87, who also spoke at the rally, faced outrage for their lack of urgency. Students and professors alike continued to disavow the University’s decision to invest, arguing that merely upholding the Sullivan Principles by these companies was insufficient.

After John Dettling ’86 was dismissed from his position as the chairman of the student government’s committee for responsible University business practices for allegedly insinuating that an administrator had lied to him, he became a powerful voice among the student protesters. Dettling asserted that the University had a responsibility to send an explicit anti-apartheid message to corporations.

“Notre Dame should be the most radical university because to be an authentic Christian is the most radical commitment,” Dettling stated in an Observer article by Mark Pankowski ’88.

Fr. Hesburgh, while not necessarily disagreeing with this sentiment, maintained that outright divestment was too simplistic an approach. He argued that other nations would simply take over the roles that divested companies left in the South African government and economy. Nevertheless, Fr. Hesburgh’s words did not deter students, who continued to protest in the subsequent months and years.

In November 1985, a group of students in Section 30 of Notre Dame Stadium displayed banners during a football game to protest the University’s involvement in apartheid. Four years later, in April 1989, another 200 students attended a divestment rally that ended in a stalemate between supporters and opponents of divestment.

Despite the outcomes of these rallies and protests, the Notre Dame student body remained vocal and undeterred in the face of injustice, demonstrating a significant communal awareness of social and moral concerns beyond the campus boundaries.

Notre Dame Apartheid Divestment Policy

Oct. 10, 1978 | Tom Jackman | Oct. 18, 1978 | Sue Wuetcher | Feb. 21, 1985 | Mark Dillon | Oct. 29, 1985| Sarah Hamilton | Researched by Cade Czarnecki

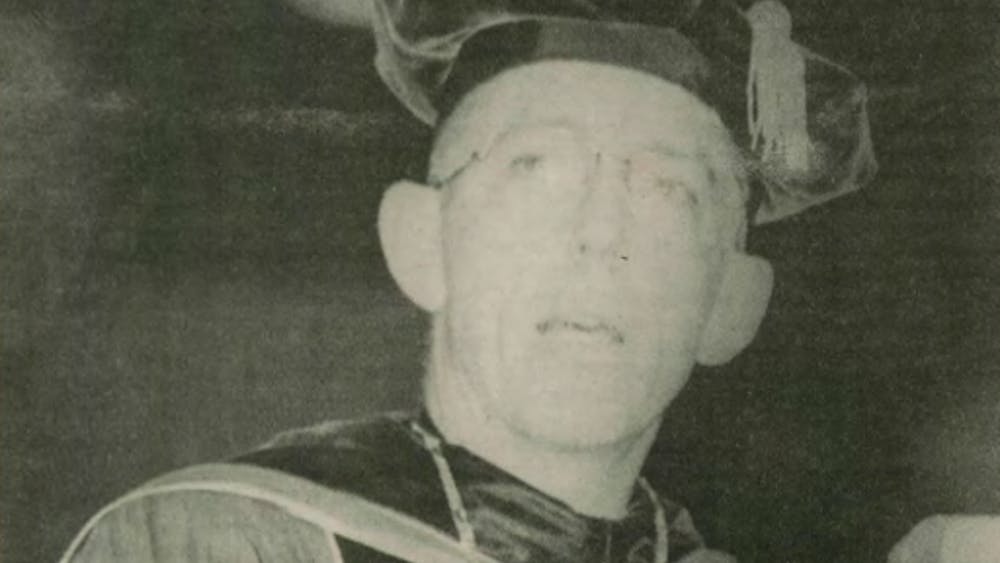

In response to several student demonstrations on campus, Fr. Hesburgh addressed Notre Dame’s potential divestiture from companies with holdings in South Africa during his annual address to the faculty senate. He declared that the University would not adopt a blanket divest policy. Instead, he stated that decisions regarding individual divestitures would be handled on a case-by-case basis.

Notre Dame planned to maintain its corporate investments and leverage its financial influence to affect policy changes in South Africa. Fr. Hesburgh argued that a complete divestiture would be ineffective, as other investors would simply take Notre Dame's place.

Over time, the official policy evolved to provide further clarity. Notre Dame decided not to divest indiscriminately but to compel the corporations it was invested in to adhere to the Sullivan Principles, which articulated specific anti-apartheid sentiments. Failure to comply would result in divestment. The Sullivan Principles were revised to compel signatories to proactively engage in efforts to end apartheid in South Africa, extending their commitment from internal company policies to broader societal change.

Ultimately, there were 11 instances where Notre Dame divested from companies that did not comply with the Sullivan Principles. Despite these divestments, about 10% of Notre Dame’s endowment fund remained invested in companies with operations in South Africa, such as General Electric and General Motors.

Notre Dame continued its policy of reviewing divestments on a case-by-case basis. The University maintained that retaining investments in companies could facilitate gradual, peaceful change in South Africa and that it could use its financial assets to promote such change.

Moreover, Notre Dame highlighted that its investments in American companies, which upheld the Sullivan Principles and employed non-whites in South Africa, were providing crucial support to those affected by discrimination.