The spirit of activism at Notre Dame is not new; historical campaigns like the six-year boycott against Campbell's Soup and debates on nuclear weapons divestment exemplify a long-standing tradition of student-led advocacy with varying success. The campus now debates whether the University should divest from companies linked to Israel during their ongoing war against Hamas.

Notre Dame’s Boycott of Campbell’s Soup Products

Feb. 26, 1986 | Amelia Munoz | Feb. 27, 1986 | Cliff Stevens & Frank Lipo | March 7, 1986 | Frank Lipo | Researched by Cade Czarnecki

Notre Dame student groups have long seen their efforts make an impact in the world beyond South Bend. Such was true during the campus’ six-year boycott of Campbell’s Soup Company products, an effort initiated by a newly formed student group.

In 1980, the Notre Dame Farm Labor Organizing Committee (FLOC) Support Group was formed in solidarity with and support of the FLOC’s efforts to improve working conditions and wages for Midwestern farm workers. These workers labored on tomato and cucumber farms which sold their produce to Campbell’s Soup Company at a fixed price set by Campbell’s.

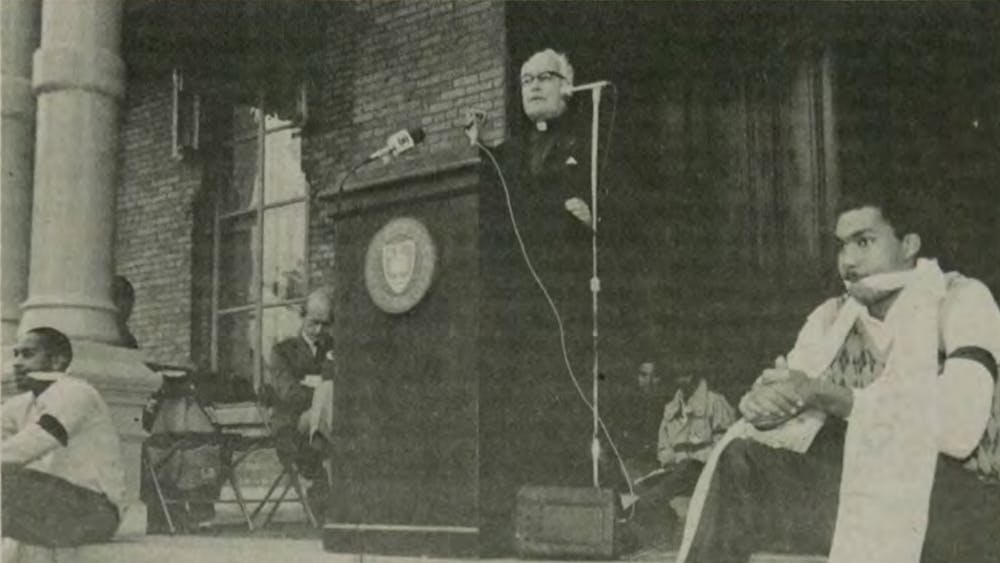

Highlighting injustices in conditions and pay, the student group persuaded the University to officially end the sale and consumption of all Campbell’s products until Campbell’s signed an agreement with FLOC to improve working conditions and wages.

Notre Dame was the first major academic institution to enact such a boycott. The boycott at Notre Dame would last six entire years. During this time all Campbell’s products were pulled from the shelves of The Huddle and both dining halls ended their relationships with the company.

Finally, after years of negotiation, FLOC signed a Feb. 21, 1986 agreement that, among other benefits, recognized FLOC as an official union, raised wages from $2.50 per hour to $4.50 per hour, granted one paid holiday per year and provided insurance for farm workers.

The monumental moment was celebrated by Baldemar Velasquez, president of FLOC, at Notre Dame. In a speech, he officially ended the nationwide boycott of Campbell’s products and vehemently thanked the Notre Dame community—and the FLOC support group in particular—for their impactful efforts in bringing about the end of farmworker mistreatment by the Campbell’s Soup Company.

Divesting from Deterrence: Notre Dame's 1984 Debate on Nuclear Weapons Investments

Feb. 07, 1984 | Jane Kravcik | May 18, 1984 | Michael Brennan | Researched by Thomas Dobbs

In Feb. 1984, the student senate called on the University to divest from nuclear weapons manufacturing, protesting nuclear proliferation amidst the Cold War. “A policy calling for the divestment of University funds from companies which manufacture nuclear weapons and their components was passed 10-3 at the Student Senate meeting last night,” reported Jane Kravcik ’87.

The policy crafted by Michael Brennan ’84 was unambiguous yet selective; it targeted companies deeply enmeshed with the Department of Defense, those that derive over half their revenue from defense contracts and those involved in producing nuclear weaponry. Brennan clarified, “The three guidelines are very limited. The University only supports one company which meets these – Lockheed.”

Assistant student body treasurer Bob Gleason ’84 presented a counter-narrative, underlining the role of nuclear weapons as a deterrent, asserting, “I personally don't see anything wrong with investing in defense. Nuclear weapons should be a deterrent. If we are pulling out, we are pulling out of defense.”

The dialogue transcended mere financial investments, touching on ethical questions about the role of an educational institution in global military engagements. Brennan commended the University for creating a “Nuclear Dilemma” course and for offering peace studies as a second major.

Brennan’s criticism, however, was steeped in a broader philosophical dissent. He referenced the stance of the U.S. Bishops in their pastoral letter, affirming, “Our government has set the priorities of our society … I think the reason for Notre Dame divesting is to say we disagree with this policy.”

The bishops’ letter, as outlined by Brennan on a later date, critiqued the “first use” strategy of nuclear deployment and advocated for stringent controls against the proliferation of these formidable arms. Brennan insisted on aligning the University’s fiscal actions with its foundational values, suggesting that where and how Notre Dame invested its substantial endowment—$250 million—was itself a declaration of University priorities and values, akin to its earlier stance against apartheid through adherence to the Sullivan Principles.

Despite the vigorous student-led initiative, the proposal met its demise at the hands of the investment committee, showcasing a stark disconnect between student activism and institutional apathy. Clashes over divestment are once again relevant at Notre Dame, compelling us to scrutinize the moral obligations tied to investments and to reassess the true impact and appropriateness of divestment strategies.