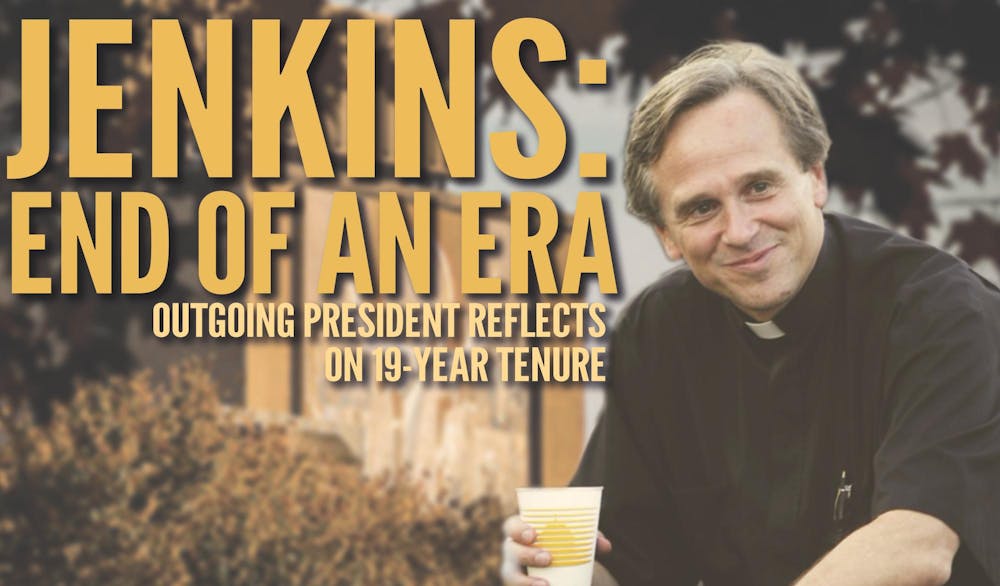

Over the last 19 years, University President Fr. John Ignatius Jenkins hasn’t had much free time.

“There are only so many hours in the day,” he told The Observer as he prepares to step down on June 1.

The occasion has not gone unnoticed. The campus community marked it last Thursday with festivities held by the Office of the President as a way of “thanking students” for supporting Jenkins during his presidency. Students received commemorative mugs reading “Rev. John I. Jenkins, C.S.C., University of Notre Dame President, 2005-2024” on one side and “Be a force for good” on the other. Later in the night, fireworks lit up the sky as protestors marched South Quad chanting about Palestine — and Jenkins himself, calling on the president to “act” on his statement calling for a ceasefire.

Jenkins spoke to The Observer earlier that day, in the first interview he’s given to the tri-campus’s independent newspaper since 2016.

The philosopher administrator

After graduating from Notre Dame in 1976 and 1978 with bachelor’s and master’s degrees in philosophy, Jenkins was ordained a priest and went on to pursue a doctorate in the same field at the University of Oxford. He wrote his dissertation on “knowledge, faith and philosophy in Thomas Aquinas.” Jenkins returned to Notre Dame to teach philosophy from 1990 until his selection as president.

When he first graduated from Notre Dame “long, long ago,” Jenkins said he did not know what he wanted to do.

“I wasn't sure what I was going to do, but I wanted to live a meaningful life, that is a life that was about something beyond myself and had meaning, beyond simply self-interest or self-serving, and I've been given that in abundance,” Jenkins said.

In “The Republic,” Plato wrote about the idea of a philosopher king, an ideal ruler who combines political skill with philosophical knowledge. Jenkins, with all his expertise in philosophy, has in a sense served as a philosopher administrator. He said that philosophy has undoubtedly shaped his outlook.

“I'm sure there are many things [from studies in philosophy] that kind of informed my work,” he said.

He zeroed in on Aquinas.

“I'd say there's a deep sense in Aquinas — going all through that tradition, from Aristotle to Aquinas and beyond — of community and our responsibility to one another, and that’s sort of very much part of what it is to be a university,” he said.

Aquinas wrote in a dialogic form, Jenkins said, harkening back to a lecture he gave his students, and Aquinas’ attempts to emulate a conversation are not unlike Notre Dame as a “community in conversation.”

Two decades of dialogue, two decades of controversy

With conversation comes controversy, and Jenkins has handled his fair share.

“Dialogue, and to an extent, controversy is what we do,” he said.

Uproar early in his tenure over performances of “The Vagina Monologues” was followed by controversy over President Barack Obama’s appearance at the 2009 commencement, the awarding of the Laetare Medal to current president Joe Biden and former Speaker of the House John Boehner, Mike Pence’s speech at commencement in 2017, Jenkins’ unmasked appearance at the White House Rose Garden and various other media cycles.

Jenkins said he regretted removing his mask at the White House while attending a ceremony for Amy Coney Barrett’s nomination to the Supreme Court, though he does not regret attending.

“I don't regret being there, because the court has been dominated by two schools, Harvard and Yale, and to have a Notre Dame alum and professor … I’m very proud of that, not that I'm endorsing [Justice Amy Coney] Barrett's views,” he said.

Jenkins said that Notre Dame has a unique position.

“Our position invites controversies that other places don't have because there's a set of values that may conflict with various views, but I feel proud that we've worked through those disagreements, controversies … that's what we should be about,” he said.

Jenkins has waded into some of this discourse on occasion, including when he wrote a letter to the Chicago Tribune distancing the University from two professors’ op-ed arguing for abortion rights. He emphasized that Notre Dame’s priority is not institutional neutrality but the University’s guiding Catholic commitments.

“As a Catholic university, we are just different than most of our peers and there's a set of moral commitments and a moral tradition as well as a religious tradition that informs our work. That doesn't mean that everyone accepts it. It doesn't mean that everyone has to agree to it. It doesn't mean that people can't speak against it. All those things can happen,” he said. “But as the leader of this institution, that broad framework should inform what we do … I tried to do that and articulate as best I could, as best I see it, what Notre Dame's broad position is.”

Balancing Catholic values with academic freedom and dialogue has been at the forefront of these arguments. Jenkins is eager to discuss Obama’s appearance as commencement speaker, which he said was welcomed.

“There was a lot of agitation, much of it from outside of the campus. But I think on campus, there was a general affirmation that the elected leader of the nation should speak and was received to speak,” he said.

On that graduation day, however, Fr. Wilson Miscamble, a history professor, spoke at a rally against Obama’s presence and argued that administrators were falling short of the University’s values.

“Instead of fostering the moral development of its students Notre Dame’s leaders have planted the damaging seeds of moral confusion,” Miscamble said in his speech.

Critics have repeated those concerns over the allowance of a drag performance on campus and other recent administration moves.

In an interview earlier in the year, Jenkins told the National Catholic Reporter he is concerned about increasing polarization among American Catholics and that some special interest groups in the Church have tried to focus solely on questions regarding gay marriage or abortion.

Jenkins will serve as commencement speaker next month, a move that has elicited some criticism from graduates in the class of 2024.

“Honored to be asked, happy to do it. Will try to give a good speech,” he said bluntly. He offered no preview of what his speech might look like.

“I can’t ruin the suspense.”

Becoming an elite university

Under Jenkins' tenure, the University has continued its ascension to the status of an elite university, becoming more selective, higher-ranked and expensive.

“I believe the world does not necessarily need another prestigious university,” Jenkins told the National Catholic Reporter. “But a Catholic university in the richest, broadest sense is something the world needs and the church needs.”

As Notre Dame has nonetheless achieved that prestige, Jenkins said that despite mistakes, he is proud of the University’s trajectory.

“I think it is a remarkable story of how not me, but the whole University has moved forward, academically but also in terms of a distinctive mission,” he said.

Two decades is a long time, as Jenkins acknowledges. He said that he has been concerned about societal trends that have occurred across the country in this period.

“I think it's a general phenomenon that people of the younger generation are disengaged from not only the Church but from many institutions, and so that does concern me a bit,” he said. “To be honest with you, what worries me most is a certain isolation.”

He also mentioned concerns over social capital.

“There's a tendency, really for society in general, but young people in particular, to have fewer friends, fewer connections. I agree with those who say that's one of the pernicious effects of the digital revolution, and those phones. We kind of connect digitally, but we don't connect humanly, and I think in the long run, that's not healthy for people, and it doesn't lead to the best outcomes of human development,” he said.

Former presidents and becoming one

Jenkins said that the examples and guidance of former presidents Fr. Ted Hesburgh and Fr. Edward “Monk” Malloy were helpful as he learned the ropes.

“One of [Notre Dame’s] strengths is a certain continuity of leadership and consistency of purpose,” he said. “Personally, Fr. Hesburgh and Fr. Malloy were very supportive of me and gave me great advice. I'm deeply indebted to both of them,” Jenkins said. “And that doesn't always happen in institutions where the new guy comes in and the old guy is shoved aside, and I hope I will be the same sort of help to my successor, Fr. [Robert] Dowd.”

While decades have passed since Hesburgh’s famous open-door policy and midnight chats, Jenkins says he didn’t feel removed from the student body.

“One of the best things about my situation is I live in Fisher Graduate Apartments and, you know, you walk to campus and you'll run into people and have a conversation with them. Sometimes it wasn't the best conversations, but those are the ways, you know … obviously, you get to interact with student government and student leaders a lot and those kinds of things,” he said.

Jenkins said he is excited for the change and looks forward to teaching rather than administering.

“I did love the job. I love the people I work with, but, you know, it's time for a change after a while — both for the University and for me — and I very much look forward to getting back to reading and writing and teaching. So I'm actually excited about that,” he said.