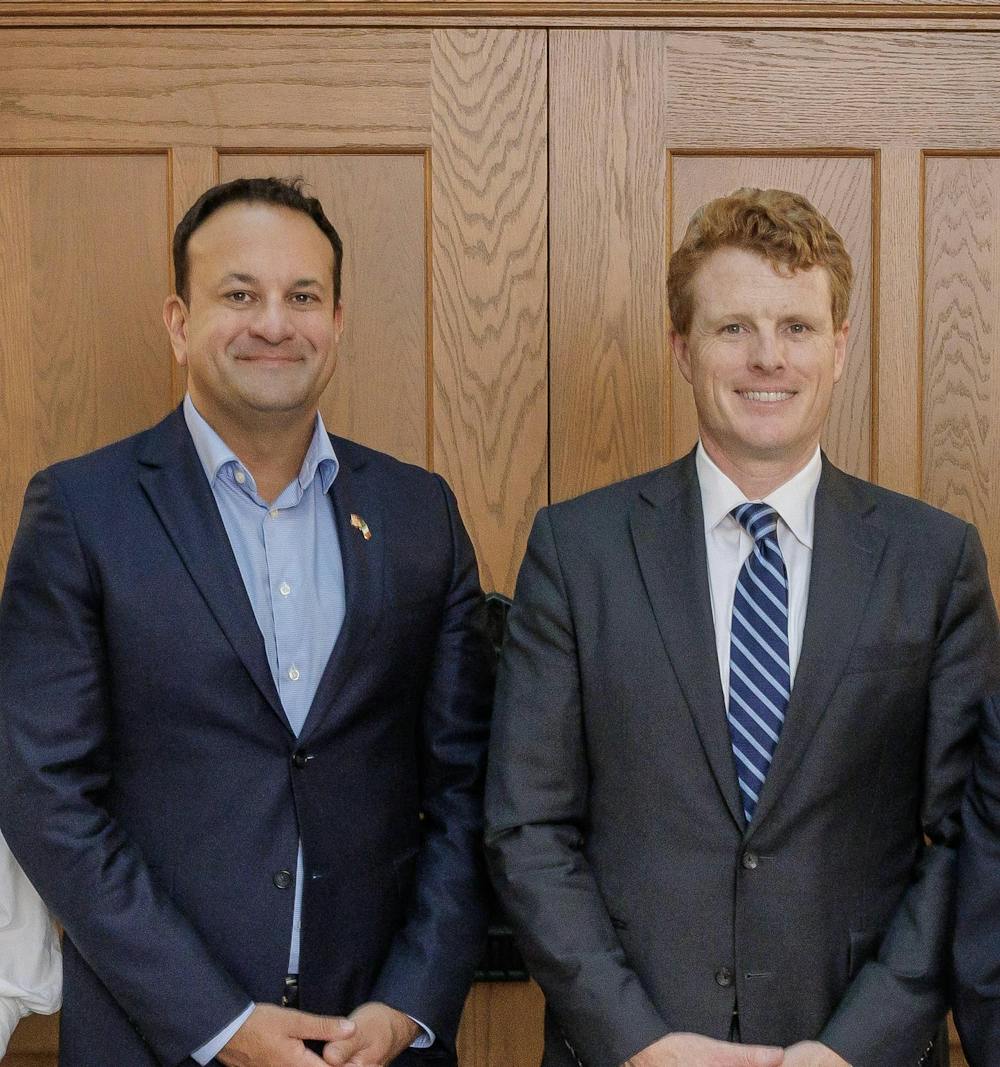

This Friday saw the arrival of two prominent figures in Irish and American politics on campus — former Irish Taoiseach (prime minister) Leo Varadkar and U.S. special envoy to Northern Ireland for economic affairs and former congressman Joe Kennedy III. Varadkar participated in a public discussion in the Hesburgh Center for International Studies in the afternoon, while Kennedy delivered private remarks at a luncheon for Notre Dame’s Ireland Council. Both events were hosted by the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies.

During their respective remarks, Varadkar discussed the possibility of a united Ireland, while Kennedy highlighted the economic and social progress of Northern Ireland in recent years.

Leo Varadkar

Varadkar served as Taoiseach (prime minister) of Ireland from 2017 to 2020 and again from 2022 to 2024, becoming the first gay and biracial person to hold the office. He resigned this March, citing “personal and political” reasons. Prior to Varadkar delivering his public remarks in the afternoon, he sat down for an interview with The Observer.

Since his resignation and the appointment of his successor, Simon Harris, Varadkar’s party, Fine Gael — who is in a coalition government with the Fianna Fail party — has improved dramatically in the polls. Six months after his resignation, Varadkar reflected on the consequences of his resignation.

“[It] was really a political calculation that my party had a better chance of doing better with a new leader,” he said. “Because people who had maybe gotten sick of us or sick of me, would look at the party again and would consider us again. And that seems to be working and working well, really in large part, because of the energy and enthusiasm of the new Taoiseach Simon Harris.”

In order for Harris’ government to be reelected, Varadkar urged Harris to call an election “sooner rather than later.” He also cautioned Harris not to let the polls get to his head, as they could easily change.

Since leaving office, Varadkar has been more outspoken in encouraging the Irish government to push for a united Ireland. He explained that now is the time to make practical preparations for such a step, as many aspects of Ireland’s relationship with the United Kingdom post-Brexit have now been settled. Nevertheless, he urged patience in pushing for a referendum on unification.

“I believe that unification should happen,” Varadkar said. “I don’t think it's inevitable. And whether it’s the referendum on a republic in Australia or independence in Scotland and Quebec, if you lose it, it’s probably off the agenda for a generation.”

A major flashpoint in Irish politics in the past few years has been the rising levels of immigration to the country. While Varadkar touted the economic benefits of migration and warned against rising prejudice and populism in the country, he acknowledged immigration was rising at too fast a pace.

“The majority of people think that the numbers have been too big in recent years, and they’re right,” he said. “A country of 5 million people seeing its population rise by 2% a year, which is what’s happening at the moment, is too fast.”

Despite his resignation, Varadkar emphasized the need to get people involved in politics and highlighted the benefits of a political career.

“While politics is tough, it’s also a privilege, it’s also extraordinarily rewarding, and that’s proven by the fact that people run for reelection,” he said. “If it was so awful, I don’t think most people would be looking to get reelected over and over again”

At 3 p.m., Varadkar took the stage at the public event with professor Colin Barr, director of the Clingen Family Center for the Study of Modern Ireland, in the auditorium of the Hesburgh Center. The auditorium was filled, with people standing along the walls to get a view of the conversation.

Varadkar reflected on his career in politics, explaining it started from “a desire to fix things that you see are wrong.” Varadkar became Taoiseach at 38 and admitted he was unsure if he was too young for the job. Seven years later, he acknowledged both the excitement and the stress of the office.

“It’s a constant roller coaster ride until the point you want to get off,” he said. “You have to keep the show on the road. You know, the economy running, society taking over, public services working, and that’s hard.”

One of the major unexpected challenges during Varadkar’s tenure in government was the Covid pandemic. Varadkar stressed that his medical background as a doctor helped him navigate the pandemic, but emphasized that “nobody got it right all the time.” He specifically acknowledged the difficulty children had learning virtually, as well as the lack of cancer screenings during the pandemic.

“I always understood when we’re making these decisions that it wasn’t just a simple choice between restrictions saving lives and people’s freedoms, that the restrictions that would save lives would also have negative consequences,” he said.

Varadkar said one of the proudest achievements of his tenure was navigating the political challenges caused by Britain’s exit from the European Union.

“We weren’t going to be taken out of the European Union in any way just because the British were leaving, and we [tried to] make sure that the Good Friday Agreement was upheld,” he said.

Again discussing the subject of a united Ireland, which he described as “the natural thing,” Varadkar acknowledged that some concessions would have to be made to unionists in Northern Ireland, potentially including enacting constitutional protections for the British minority, changing national symbols and deemphasizing the Irish language.

“You have to craft a proposition that people are willing to buy into,” he said. “Certainly, the vision for a 21st century united Ireland is not the vision of 1916.”

Joe Kennedy III

U.S. special envoy to Northern Ireland for economic affairs Joe Kennedy III spoke with Professor Patrick Griffin in Jenkins-Nanovic Hall. Courtesy of Ryan Juszkiewicz.

Before Varadkar’s public event, Kennedy spoke to members of Notre Dame’s Ireland Council in Jenkins-Nanovic Hall and sat down for a conversation with professor Patrick Griffin, director of the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies. Kennedy began by emphasizing the United States’ special connection to Ireland.

“In the United States, where partisanship seems to be tearing up the fabric of almost everything we’ve done, Ireland is one of the few things that still pulls everybody together,” he said.

In spite of the legacy of the violence and division of The Troubles in Northern Ireland, Kennedy highlighted the economic and social progress Northern Ireland has made in recent years.

“Look at artists, catalysts, driving innovations, not just here in Northern Ireland, but around the world. Watch the skyline as a harbor in Belfast changes as new buildings sprout along the street,” he said.

Economically, Kennedy also highlighted the highly educated workforce, the increasing job opportunities and the cheaper cost of living in Belfast compared to cities like Dublin or London.

Kennedy’s position of special envoy to Northern Ireland was first held by former U.S. Senate majority leader, George Mitchell, who helped negotiate the Good Friday Agreement in 1998, bringing an end to The Troubles. Kennedy emphasized that while Mitchell’s shoes were big ones to feel, he was honored to hold the position.

“By the nature of leveraging title and connection and platform, hopefully, you can artfully call out some of the challenges that are there and then nudge people towards those solutions,” he said. “We can choose to fix it, or we can choose not to.”

Kennedy stressed there is both a technical aspect of the job, which entails trying to foster economic development in the region, and a symbolic aspect which shows the commitment the United States has to peace in the region.

In an age of political polarization, Kennedy pointed to Northern Ireland as an example of how to bridge social divides and build peace.

“The United States could do well to learn a few things from Northern Ireland. Today, more than ever, we are seeing dangers of political violence threatening the stability of democracy,” Kennedy said. “There’s a lesson from Northern Ireland. It is that peace is precious and we need to care for it.”

A key part of fostering this peace, Kennedy said, involves ensuring that opportunities are open to both Catholics and Protestants and that the two communities view the advancements as favorable to everyone.

“Growth and opportunity here is not zero-sum. If you can feed your family that doesn’t mean I can’t feed mine,” Kennedy said.

Like Varadkar, Kennedy also acknowledged the destabilizing effects of Brexit on Northern Ireland.

“I’m not certain that all of the ramifications of the UK leaving the EU were wholly explored vis a vis what that would mean for Northern Ireland when that vote was taken,” he said.

Nevertheless, Kennedy noted opportunities for an improvement in the United Kingdom’s relationship with Ireland and, by extension, the European Union with a new government led by Keir Starmer and the Labour Party. Kennedy noted the Labour government has expressed more interest in moving closer to the European Union than the previous conservative government.

“There’s an opportunity though with any government change to reset some of these relationships and take a look with fresh eyes,” Kennedy said.

Kennedy also offered praise for Varadkar, who was in the audience, citing the economic success of Ireland in recent years.

“It is a reflection of what can happen when leaders choose to leverage their political capital to take on challenging issues for the sake, for the betterment of their people,” he said.