To myself, for myself, for the world,

As I tediously attempt to will into existence the thousand odd words necessary for this article — and fail time after time — I begin to wonder why I write in the first place. Sure, I’m talented enough — my ego won’t deny that. Moreover, I often derive a deep sense of fulfillment from the act of stringing together words into coherent, compelling and resonant thoughts.

But who am I, in the midst of this oft-fruitless process of stringing together words, to stumble upon some particular thought that has yet been expressed by another writer? And if I do happen to stumble upon this particular and unique thought, chances are, someone else did too, and possessed the ability to convey it with far more rhetorical brilliance than ever could I. I’m not Dostoevsky, nor Kierkegaard, nor Camus, and so if I can’t level with the mastery of the greats, then why even bother?

This doubt in my abilities as a writer, and in my seemingly-rash desire to pursue the discipline further, gives rise to insecurities pertaining to my own self-worth. Not in a self-loathing kind of way, but in the way that comes about when one feels absolutely certain of some particular thing, then comes to question not only that thing, but their once-foolish certainty in said thing. It’s a deeply humbling experience — is it not?

I tell people I want to be a writer. I tell others I am a writer. I tell myself I’m the best f*cking writer on the planet. But then, on a night like tonight, I can’t write. I seek out the requisite words, I call upon the faculties that typically produce the most eloquent of syntax, and yet I find only lacking fragments of worthwhile thoughts and am left to wrestle with the proposition that I am sub-par excellence at this endeavor into which I’ve staked so much of my being.

This, I think, is the humbling part: to stake a significant portion of your being into some particular pursuit, only to be proven less-than masterful — if even good — at said pursuit. This unexpected imposition of humility calls into question the whole of our worldviews — in one moment, we think ourselves to be deeply efficacious at some particular undertaking; then, in a completely separate moment, we are unable to comprehend how we ever thought ourselves competent in said undertaking, which we now flounder at most spectacularly.

This is the plight of the artist, sure, but really, it is the plight of the human being. If one ever dares to think themselves good at anything, then fails at that thing, they will be made to grapple not only with their ineptitude at such a thing, but also with their inability to make truthful approximations of reality. A helpful example to clarify what I mean: I give a presentation and speak without a trace of self-doubt to such an extent that I think of myself as possessing unshakable confidence. Then, I run into my crush, and am wrought with nerves — my voice shakes (oh, how tragic an occurrence! Is there any feeling more vulnerable than to be the victim of a trembling voice?!) — not only that, but my reddened face does little to conceal my now-flustered state.

Moments earlier, I had coronated myself with the crown of eternal confidence, but now, that self-assuredness has been irreparably lost, and so I dawn only a flimsy paper tiara, which glimmers the most foolish of golds. Is this not what it feels like to be confronted with the humbling realization that we are not who we once thought we were? Worse yet, we come to believe with such immovable certainty that we are indeed this great person so that when circumstances are such that we can no longer believe this untruth, our worldviews are annihilated — how can we ever again be trusted to formulate accurate perceptions of reality?

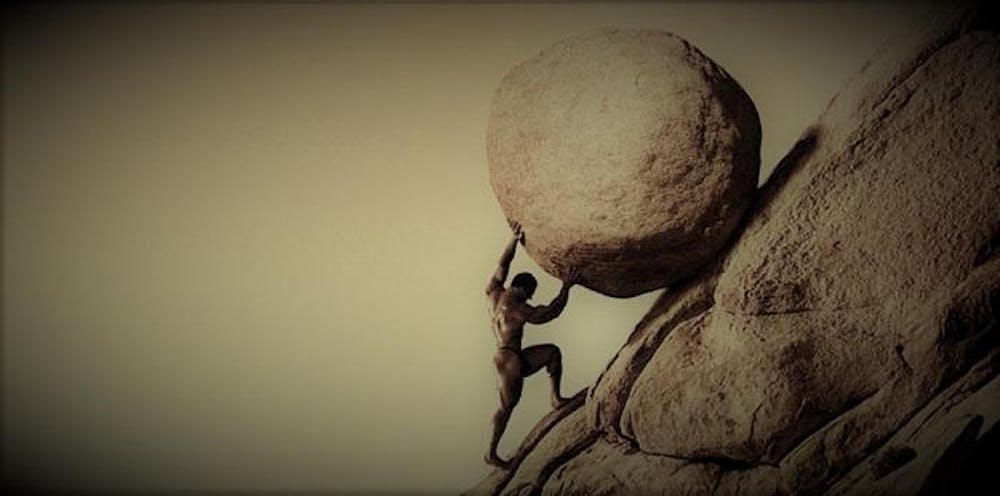

So here I sit, substantive words finally emanating from my fingertips, yet now unable to think up a satisfactory conclusion to this “exposé”. The inclination is to moralize, or to force upon this piece some unsupported, yet edifying takeaway that gives us all reason to celebrate shared hardships. But instead, I’ll call upon the plight of Sisyphus, the Greek mythological figure condemned to roll a large boulder uphill for eternity, only for that boulder to come barreling back down upon nearing the summit.

Is this myth not deeply analogous to the condition I have described above — that perpetual cycle of immense self-belief, soon and invariably followed by crushing self-doubt? The action which shatters that self-belief, the action which prohibits us from continuing to believe an untruth about ourselves, that action is Sisyphus’s boulder rolling back down to the foot of the hill. And we, much like Sisyphus, are fated to look on helplessly, before gathering together the pieces of a now-fractured self-identity and acknowledging that we must always strive upwards on this eternal hill, if only for the sake of not going down.

In Camus’ own unmatched brilliance: “The struggle towards the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

Yours defiantly,

T.W.

Jackson is an aspiring philosopher and nomadic free-spirit. He is currently wandering through an alpine meadow somewhere in Kashmir, pondering the meaning of life. If you would like to contact him, please send a carrier pigeon with a hand-written note, addressed to "The Abyss." He won't respond. (Editor's Note: you can contact Jackson at jlang2@nd.edu)