There’s nothing like existential crises on Saturday morning: waking up to find oneself in the bedding of future dread and past transgressions, comforted solely by the sound of a new album from a forgotten favorite.

The Cure had been on my favorite bands lists since the dawn of my punk-rock phase in early high school. Not much has stuck with me from that time, but what did was either insatiably catchy or simply great. Weezer, for instance, barely survived.

The Cure, however, never strayed. “Boys Don’t Cry,” “Friday I’m in Love” and “A Letter to Elise” were hypnotic. At the time, the band was merely an upbeat set of classics to be played on relatively casual afternoons. My parents knew them, Target’s overhead speakers knew them, and I loved them. Though their lyrics were thematically dark, the melodic happiness hid the angsty undertones, and I was content in my punk-rock era.

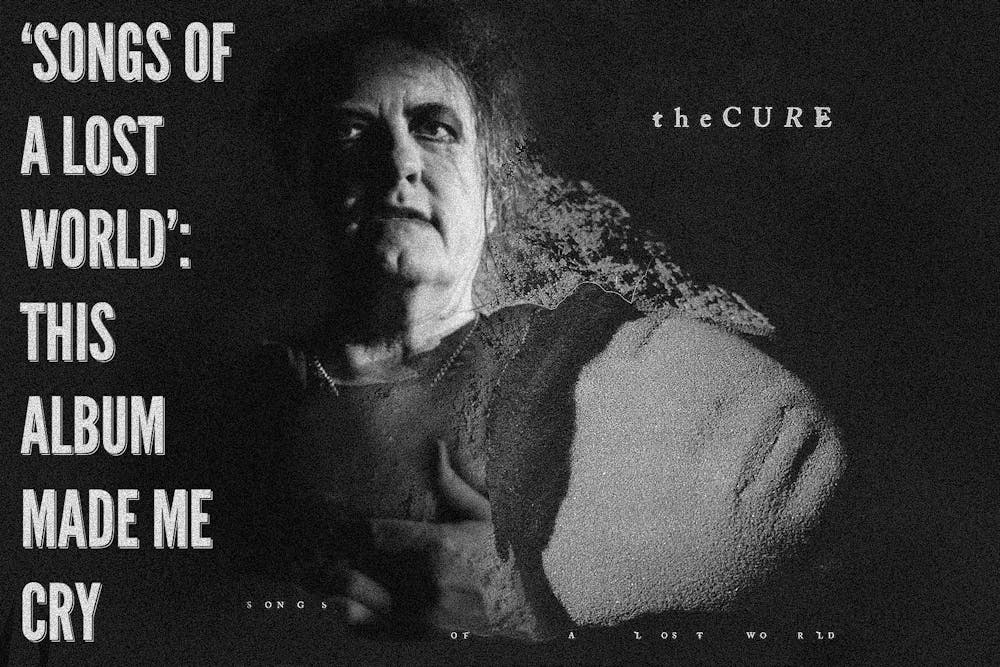

This preference for The Cure’s upbeat melodrama diminished when I listened to the entirety of “Songs for Lost World” that Saturday morning. I found myself engrossed in the existential commentary and the heart of the lyrics. Unapologetically dark and dreadful, the album pierced an unknown fear of hurt, age and regret in my soul.

“Alone” opens the album. The song reaches nearly seven minutes and is full of dark instrumentals and breathtaking lyrics: “But it all stops / and we close our eyes to sleep, / to dream a boy and girl / who dream the world is nothing but a dream.” To open an album with a message as heavy as “ends are imminent, so what do we value?” is a potent move. The lyricism allows the listener to appreciate the narrator’s discovery of what is and is not important at the end of his life, career, or what have you.

By “Warsong,” the album’s fourth song, the toil of life overcomes the narrator. The lyrics are aggressive and the delivery is blunt: “For bitter ends we tear the night in two, / I want your death, you want my life.” Later the lyrics continue, “All we will ever know is bitter ends / for we were born to war.” It appears the narrator believes there is not much else to do but fight. There is not much humanity is capable of other than to war with one another. Do we exist to conflict with one another and to conflict with ourselves?

I hate to spoil it, but this is not a story wrapped in a happy ending. The album is real. In some of the final lyrics of “Endsong” — “No, I don't belong here, / it’s all gone, it’s all gone, / I will lose myself in time, / it won’t be long” — the narrator seems to have lost the will to live. What value there once was in life no longer exists. Here we find that the question prompted by “Alone” has been answered — love mattered but no longer can love be found. Therefore, if love no longer exists neither should the fight continue.

Saturday morning, “Songs of a Lost World” made me cry.

What dampened my dawn? It was not nostalgia for my earlier years of punk-rock angst, nor was I caught off guard by any means. The album touched a vulnerable aspect of humanity that I deeply enjoy worrying about. Though not at the end of my life, I fear the end. I fear loneliness and purposelessness. I fear “Endsong.”

Although heartbreaking, the album emits hope — the hope that love always exists here. We just have to keep fighting for it. And I will keep fighting. I will keep fighting to escape an aimless end amidst a lovely reality hidden by a dreadfully dark world.

“Endsong” is not reality nor can it ever be reality. Love does not simply diminish over time. It exists despite time. I still love The Cure after 16 years album-less and 16 years worth of growth since my angsty punk-rock era. I still love the memory of my parents singing to “Friday I’m in Love.” I love this album. I think and I hope that all things I love will exist with me until finally, I am aged.