When asked to describe the Center for Zebrafish Research (CZR), professor David Hyde, the memorial director of the research center, called it a “giant pet store.” The CZR, a 3,000 square-foot facility in the Galvin Life Science Center, houses about 100,000 zebrafish. As one of the largest zebrafish systems in the United State, the facility has been used extensively for biological research.

A few decades ago, Hyde helped to put in place Notre Dame’s first zebrafish tanks with the resources and space provided by Francis Castellino, the dean of the College of Science at the time. The first batch of zebrafish was received from University of Oregon Zebrafish Information Resource Center (ZIRC). Hyde discussed how zebrafish research facilities have continual exchanges with one another in order to further research initiatives.

“The zebrafish community, which is quite large throughout the world, is very open and generous,” Hyde said. “We’ve gotten fish from all over the world. We’ve sent fish all over the world to other people who’ve asked for them, because we have some fish that basically were created here at Notre Dame [that] either contain specific mutations or express specific genes, [making] them unique in the world, so we’ve shared those with other labs."

With his own lab research focusing on the regeneration of retinal neurons, Hyde explained how the zebrafish serves as a favorable candidate for a variety of biological research experiments.

“From a single pair of fish, we can get up to 200 fertilized eggs per week,” Hyde explained. “If we want to do genetics, we can get large numbers of progeny.”

Because the female extrudes the egg, Hyde explained, the embryonic occurs outside the female, which makes it easier to study.

“In addition, the developing embryo is transparent, so we can actually see internal organs, the heart, the brain and the kidney,” Hyde added. “We can see them develop, and we can see things happening with them.”

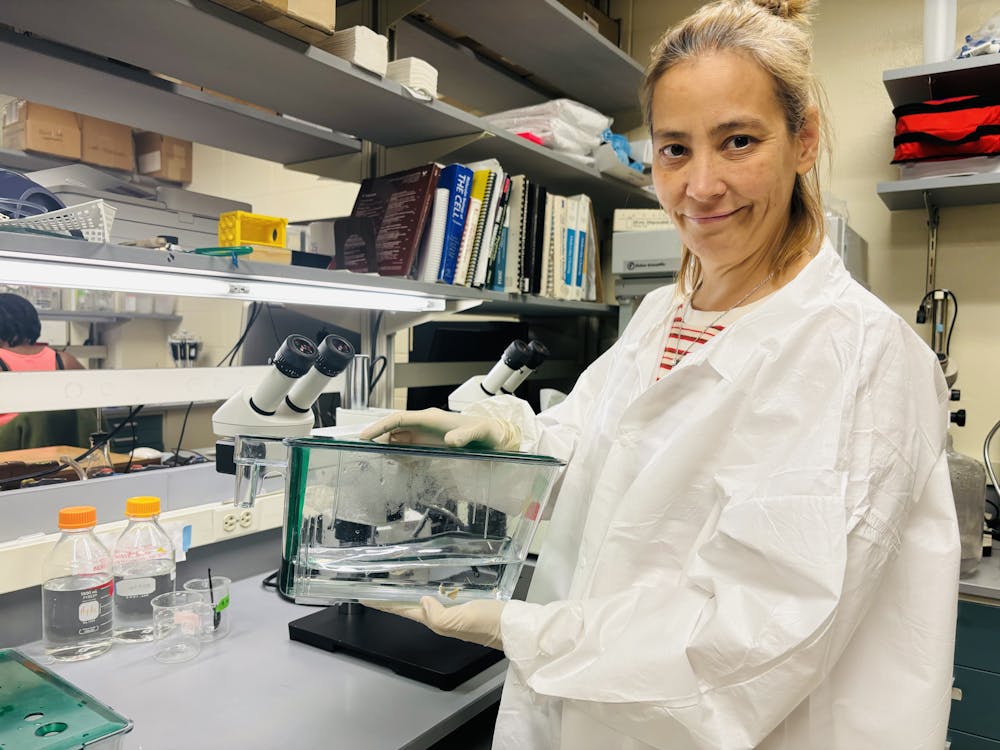

Aside from the zebrafish’s reproductive capabilities and transparent embryo, the zebrafish’s ability to regenerate cells has also proven essential in research. Maria Iribarne, a senior researcher scientist in the Hyde lab, discussed the usefulness of zebrafish’s capacity for regeneration.

“They are super successful to regenerate,” Iribarne stated. “[We] try to understand how they can do it, understand all the molecular pathways. And the idea is, in the future, we will transfer that information and induce similar results in the mice or humans.”

With the zebrafish’s regenerative capabilities, a number of research projects have been performed in conjunction with the Center for Zebrafish Research. Andrew Button, a third-year graduate student in the Hyde lab, is one of the researchers conducting experiments with the zebrafish.

“My project involves creating a transgenic zebrafish line,” Button explained. “I've created a new transgene, a gene from another animal, and I put it into the zebrafish. A lot of what I work with is the people in the fish facility who help me keep certain fish lines that have different transgenes, so that we can use them for different experiments.”

In addition to conducting extensive research with the zebrafish, Hyde emphasized the importance of proper maintenance. Due to different genetic mutations, there are approximately 50 different zebrafish lines within the facility and this calls for specific procedures tailored to each type of fish.

“Some fish get fed three times a day. Some get fed two times a day,” Hyde stated. “We have outstanding animal technicians who take care of the fish, they monitor their health, they do the feeding and they help with some of the breeding of the fish.”

Aside from basic maintenance for the zebrafish facility, the CZR also adheres to specific protocols when handling the zebrafish in experiments. Hyde explained how the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) must approve all procedures performed with the zebrafish to ensure ethical treatment of the animals.

“When we study traumatic brain injury, we basically anesthetize [the zebrafish], cause the traumatic brain injury and then monitor how they are recovering,” Hyde shared. “In the protocol that we write that has to be approved by the IACUC committee, we have to describe after we damage [the zebrafish] how we are going to monitor them to make sure that they're not in any sort of unnecessary pain or discomfort.”

Hyde continued to connect back to the zebrafish’s regenerative capabilities.

“In our case, because the fish regenerate, even though we blind them, even though we give them a traumatic brain injury, they regenerate their neurons, so that they're functioning perfectly normal within a matter of a couple weeks,” he said.

With more interesting research projects in the near future, Hyde discussed his goal of increasing collaborations with other fish facilities to share knowledge and benefit the global zebrafish research community. In particular, Hyde shared his hopes of sharing the technique with other institutions as well.

“We’ve set up collaborations with groups at Johns Hopkins, University of Florida, Florida State and the Cleveland Clinic to try to take what we’ve learned in fish and try to translate it into what happens in mammals like mice,” Hyde said.

“We [are] planning to perhaps expand it, [and] continue having more collaborations with other institutions with zebrafish,” Hyde continued. “The University College Dublin is going to be sending a postdoc here in the spring to learn how to do certain techniques that we developed here at Notre Dame, so they can learn the technique and take it back to Ireland and share with other people there.”