Last January, I ditched my dying iPhone and bought a $35 Nokia. Everyone called it a ‘flip phone,’ but it did not even boast a second layer to flip open or slide out, as did many phones from the 2000s. My Nokia was barely larger than a business card and looked more like a mini walkie-talkie than a phone. A small, pixelated display covered the top half, and a number pad and other buttons covered the bottom. It could call and text but did not support group chats and had no camera, no maps, no internet and no social media. (It did have the game Snake, though.)

Dialing a number or calling one of my contacts was easy enough, but writing texts on the number pad took a while. (To type ‘hello,’ I pressed 44-33-555-555-666.) My connection was abysmal, especially on campus, except for a few hotspots I eventually discovered, where I often had to go to make calls and send messages.

On the other hand, my screen time, which was already low, plummeted to effectively zero.

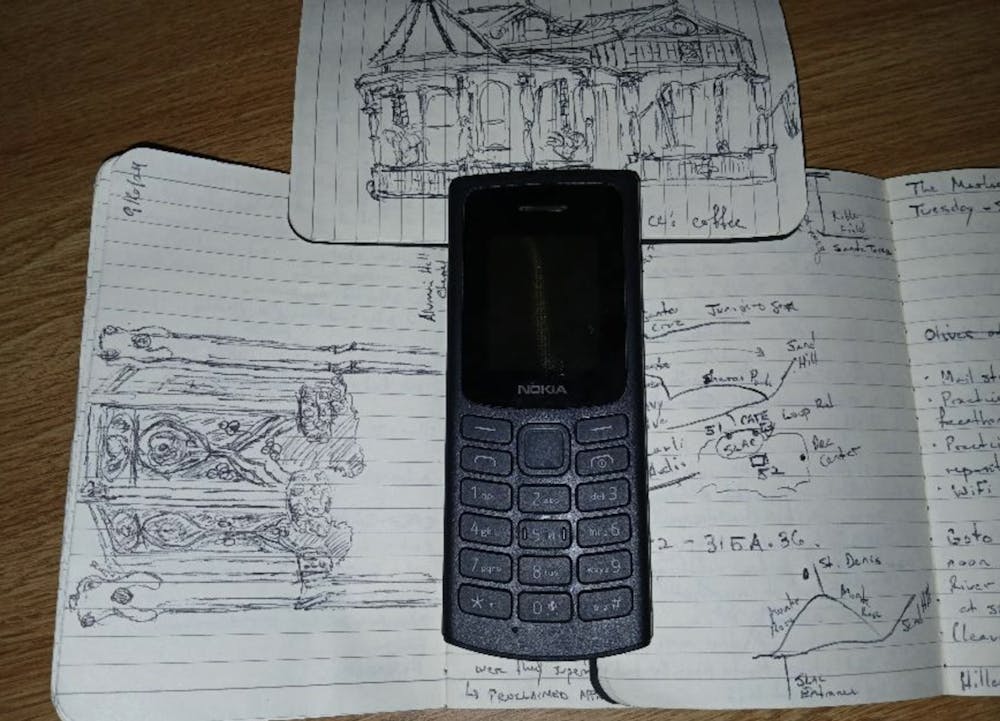

I had no way of distracting myself from a conversation, a book or an assignment, even if I wanted to. I became very comfortable being bored, very used to sitting with my own thoughts while staring into space. I learned to look longer at beautiful things, letting the world sink into me for my memory, rather than capturing an image for my camera roll. I started carrying a small notebook with me so I could jot down dates and times, directions, to-do lists, schedules and plans — all the things that typically crowd a Google calendar — as well as miscellaneous thoughts, notes and sketches.

I traded the conveniences and flash entertainments of my iPhone for the treasures hidden in the world in plain sight, buried in books or waiting to be unearthed in simple conversations with plenty of eye contact. I traded my iPhone’s most powerful tools, which I had used to get or do what I wanted when I wanted, for peace of mind, a long attention span and a will unburdened by the guilt of wasting my time. Like all trades, I had to give up things and make sacrifices; but, like all good trades, what I gained was worth more to me than what I lost.

A common response I got from people when I showed them my Nokia was, ‘Why would you go out of your way to make your life harder?’ These people saw only the conveniences I had lost and not the treasures I had dug up through the labor of inconvenience.

Another common response was, ‘Wow! Props to you, but I could never.’ I believe these people underestimated themselves. I admit that the world is designed for iPhone users and that many practical tasks seem to absolutely require an iPhone (or some kind of smartphone). But there are still old-fashioned ways of doing most things. If you are willing to make the sacrifices, to jump ‘off the grid,’ you will learn to find a way, because you have to find a way, because you are perhaps smarter, more resilient and more resourceful than your iPhone says you are. Here are some of the ways I dealt with miscellaneous practical tasks:

- I looked up directions at home on my laptop and wrote them down in my pocket notebook. I started memorizing routes, and internalizing maps and I learned to pay attention to street signs and to ask for help when lost.

- I used the printers on campus or the scanner in the library to scan and submit homework without taking pictures.

- I rerouted my methods of two-step verification (e.g., for Otka) from push notifications to sending me a code via text.

- I printed out all tickets with QR codes, boarding passes, etc. For my football tickets, I emailed the Ticket Office and picked up printed tickets at the Ticket Resolution Booth (which I did not even know existed).

- I sent links and photos back and forth via email. I started checking my email only a couple of times every day. Anything I wanted to look up, I wrote down and waited to look up on my laptop.

To some, this maneuvering may seem pointless (‘That’s what a phone is for!’), but to me, it was a price I was willing to pay for freedom from distractions.

But since October, when I replaced my Nokia with an upgraded dumb phone called the Wisephone (the other popular dumb phone you may have heard of is the Light Phone), I have been in the best of both worlds: freedom from distractions and freedom from inconveniences. The Wisephone has the hardware of a standard Samsung phone, with a nice touchscreen and multiple cameras, but its software is modified to allow only certain functions and certain apps.

I now have a perfectly reliable connection, can text again in group chats on a full keyboard, can take photos, listen to music and navigate with maps. There is still no internet, no social media, and no email. My Wisephone eliminates the inconveniences of my Nokia without adding distractions (no, this is not an ad), but I am not sure whether I would have reaped all the aforementioned benefits (peace of mind and will, comfort in silence and boring, ordinary life, absorption in books or in natural beauty, etc.) if I had gone straight to the Wisephone without the Nokia.

I am not sure whether this account of my experience is more likely to scare you away or convince you to get a dumb phone. In any case, it is the honest experience of someone grappling with how to use — and not be used by — technology in this modern world, and I hope there are things you can glean from it for your own life.

Richard Taylor is a senior from St. Louis living in Keenan Hall. He studies physics and also has an interest in theology. He encourages all readers to send reactions, reflections or refutations to rtaylo23@nd.edu.