We’re coming up on the fifth anniversary of the COVID-19 shutdown. Maybe the news department or the “From the Archives” people will write something about that, but for the intents and purposes of this section — we who care more about Broadway minutia than Walk the Walk Week happenings — the real pandemic of the early 2020s might as well have been hyperpop.

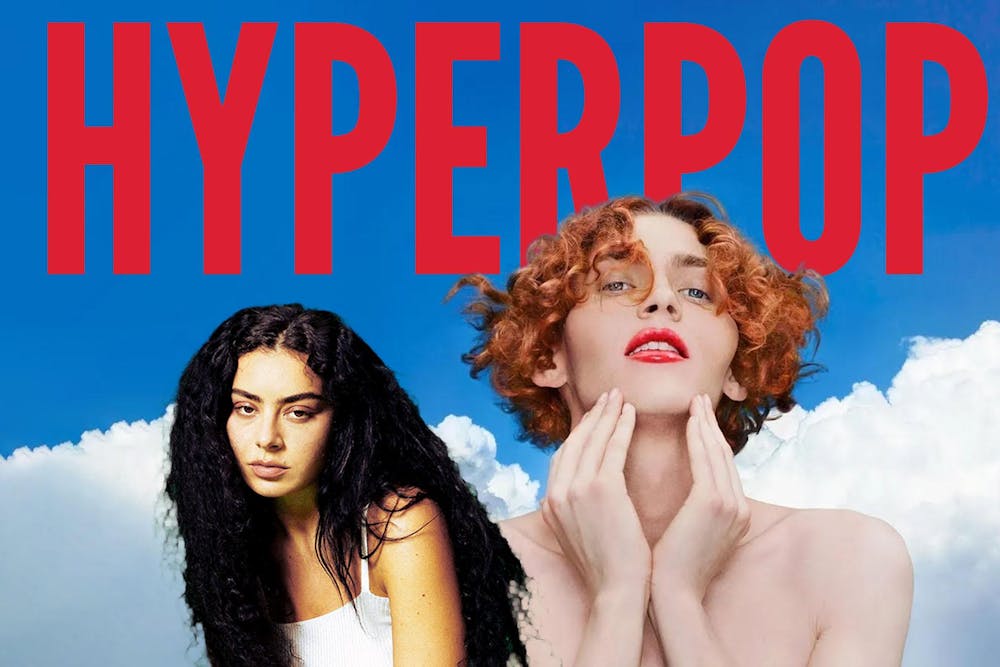

Of course, as a genre, hyperpop had a pre-COVID history. “1000 gecs,” probably the most popular album in the style, had been out for almost a year by the time of the outbreak. Charli XCX and SOPHIE’s “Vroom Vroom,” one of the movement’s early masterpieces, was released in 2016.

Still, hyperpop really started to gain traction — and importantly, its moniker — during the lockdown. The music spread across TikTok (when the app was first gaining its cultural ascendancy) like wildfire, and its fans tore across the internet like Huns.

What, then, was hyperpop? It was different things at different times in different places to different people. That is to say, hyperpop made in the early or middle part of the 2010s in Britain was substantively different from later hyperpop in America.

British hyperpop was born out of that nation’s club tradition. It was closely associated with the label PC Music, which was led by A. G. Cook and signed acts like Hannah Diamond, GFOTY and Danny L. Harle. Before the term hyperpop (which many of these acts always disliked), this genre was oftentimes just called “PC Music.”

SOPHIE’s records are the prototypical example of this strain of the style. It was bright, clean and hard — and probably meant to be listened to on MDMA.

American hyperpop came later, and felt dirtier — i.e., more weed-coded. It was a movement led by Skrillex admirers who dressed basically like My Chemical Romance fans. Many of its producers came not from high-brow metropolises but from second-tier American cities. This music, unlike its cousin across the sea, took a lot longer to jump from SoundCloud to Spotify.

All of these threads were united under the name “hyperpop.” While, in general, artists are too precious about labels — they all think they’re too good for them — it was a little odd how an Estonian rapper called Tommy Cash and a married lady from St. Louis named Laura Les came to be lumped together under one umbrella, for example.

Nevertheless, there was a golden age. Its most beautiful expression is probably Charli XCX’s “how i’m feeling now,” composed during the first summer of the pandemic.

I ought to note three other things:

First, music critics were exceptionally fond of hyperpop. In some sense, it was an outgrowth of the poptimist attitudes of the Pitchfork days.

Second, the community was always disproportionately transexual.

Third, the hyperpop fanbase underwent a demographic transition during the pandemic. When I went to a pre-pandemic Laura Les performance, there was an awe-inspiring mix of zoomer twinks and millennial women and 50-year-old men. After hyperpop exploded on TikTok, the proportion of female teenagers in graphic eye makeup at the shows quintupled. (This isn’t a value judgement, just an anthropological observation.)

Every empire has its decline and fall, of course. Charli XCX began to insist that hyperpop never existed, that it had always just been pop music. Hyperpop eventually lost its pride of place in the discourse, although its artists didn’t disappear. Charli returned to selling herself as a club act, and many other figures from the British scene with her. American acts became more and more eclectic — e.g., 100 gecs got a lot more interested in real instruments.

There still seems to be a healthy contingent of hyperpop-style DJs in a lot of cities, though. Foodhouse (the true believer’s favored hyperpop group) is even releasing their sophomore album this February.

Hyperpop was originally a genre by millennials for millennials, and then it was by millennials for zoomers and finally it became by zoomers for zoomers. That newest crop of artists isn’t going anywhere any time soon, I think.

Take punk. It’s not what it used to be, but — as its fans insist — “punk’s not dead.” And they’re right. Punk will never die because it’s easy to make and it’s fun to watch. It’s a self-perpetuating scene like that. My money’s on hyperpop heading in a similar direction.