God, country, Notre Dame.

These words emblazoned above the side door of the Basilica of the Sacred Heart memorialize the 56 Notre Dame men who sacrificed their lives for our country in World War I. The phrase represents Notre Dame’s commitment to the United States of America, a civic faith that comes second only to our faith in the Creator.

Though it bears a French name and an Irish mascot, this is a decidedly American university. Notre Dame’s story has always been rooted in the promise and opportunity of this land, and it has a long-standing role in the civic life of the United States. America is what made Notre Dame possible, and it has never forgotten that. When the Union needed chaplains, Notre Dame sent its priests. When the Ku Klux Klan descended on South Bend in 1924, its students drove them out. When the nation confronted segregation, University President Fr. Ted Hesburgh helped draft the Civil Rights Act and stood with Martin Luther King Jr. Through war, intolerance and injustice, Notre Dame has never stood on the sidelines. It has led.

This commitment to country has long been an element of Notre Dame’s commencements. Less than a month after the conclusion of the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman spoke at the 1865 commencement to counsel the young men of a country that had been torn apart and successfully fought to save itself.

A broad spectrum of United States presidents have addressed Notre Dame graduates since President Dwight Eisenhower, each speaking in some way to our patriotic obligations. Even earlier, President Franklin D. Roosevelt spoke at a special convocation in 1935, receiving an honorary degree. Our nation’s first Catholic president, John F. Kennedy, followed in the steps of his father and grandfather to speak at a commencement ceremony 10 years before his election to the highest office.

When Eisenhower spoke, he was a last-minute invite. But many an accident on this campus has evolved to become tradition. The tradition of presidents speaking at a Notre Dame graduation, typically in the first year of their presidency, continued with Carter, Reagan and both Bushes. Gerald Ford spoke at a St. Patrick’s Day convocation and received an honorary degree in 1975. Bill Clinton spoke at a Stepan Center rally late in the 1992 campaign. President Barack Obama spoke in 2009, with vociferous opposition from critics who viewed his stance on abortion as irreconcilable with Catholic teaching.

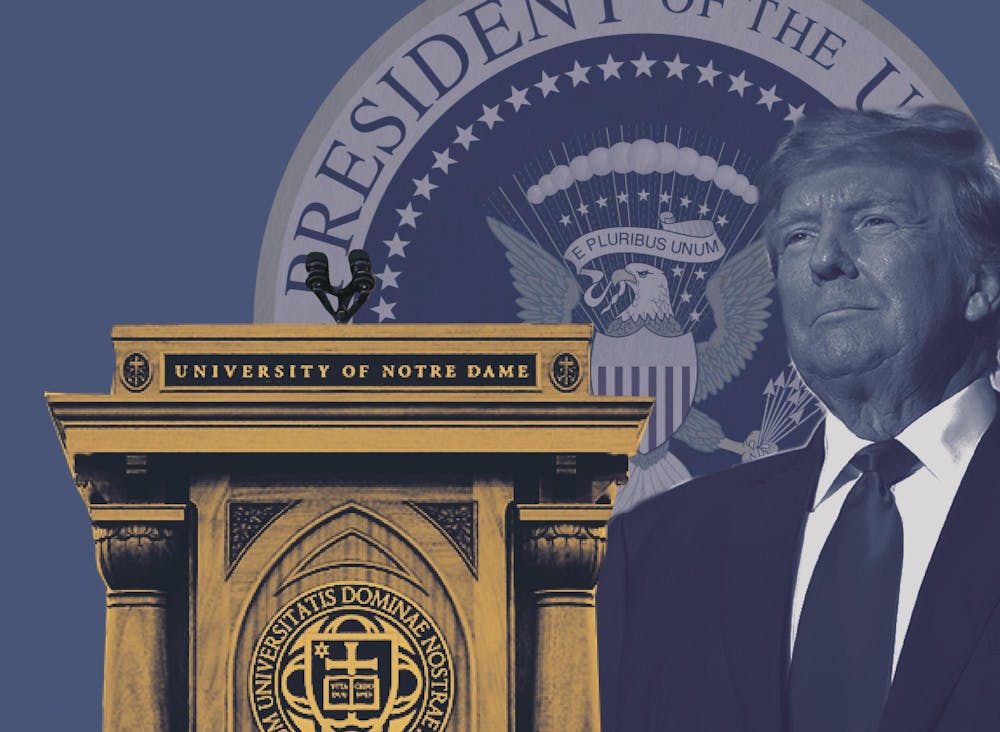

Even when a speaker is divisive, the office they hold — and the ideas they bring — demand engagement, not retreat. That is why the University invited Obama in 2009. And it is why, in 2025, Notre Dame should invite President Donald Trump.

Trump’s presence, like Obama’s before him, will ignite controversy — for reasons both personal and political. His character is deeply polarizing: crude rhetoric, habitual dishonesty, a history of proud philandering and flagrant disregard for basic decorum. His administration’s policies are no less contentious. Policies from the Trump administration’s enabling of migrants to be arrested in churches to its ambitions for Gaza will — and should — come under fire. When Obama spoke, he was met with loud opposition from critics who argued his abortion views were out of line with the Catholic faith. There’s no question that Trump too will face criticism, for a thousand reasons.

While this dialogue is essential, what opponents to inviting Obama or Trump miss is that this is bigger than one man or the politics of the day. Notre Dame’s relationship with the civil fabric of this nation — and its head of state — is a special one. If she had won, Kamala Harris should have been invited. On principle, the invitation to the president is too significant a tradition to lose. In 2017, Trump wasn’t invited on the grounds of “moral decency,” according to former University President Fr. John Jenkins in a 2024 interview. While that remains a valid concern, Trump was an anomaly in 2017, and unfortunately is not in 2025 after a decisive election victory. He is no longer beyond the pale to much of the American public as he might have been in 2016. In 2021, Biden declined the invitation, a curious decision from the nation’s second Catholic president. If Notre Dame fails to extend an invitation this year, it will be the last nail in the coffin of a long-standing tradition.

We’ve had unsavory and controversial figures speak at commencement before, and not just the aforementioned presidents — figures whose legacies, in hindsight, range from complicated to outright disgraceful. J. Edgar Hoover weaponized surveillance and blackmail. José Napoleón Duarte’s government was linked to death squads. Earl Warren, a civil rights champion on the Supreme Court, first helped orchestrate Japanese internment during WWII. And yet, Notre Dame extended the podium to them — not as an endorsement, but because engagement with powerful figures, even flawed or reprehensible ones, is part of what it means to be a great university. We understand that Trump is personally repulsive to many, including the members of this board.

To those who fear that inviting Trump normalizes his worst behavior, we counter that ignoring a sitting president does nothing to hold him accountable. If anything, granting Trump the stage forces him to confront an audience that is not unconditionally adoring, that expects a level of propriety and reflection worthy of the occasion.

Under University President Fr. Robert Dowd, Notre Dame has repeatedly voiced its desire to encourage dialogue and debate on campus, even with those with controversial or unpopular opinions. Notre Dame, unlike other campuses in this country, aspires to the capacity for respectful dissent, whether in the pages of this paper or silent protests during the ceremony. While Trump degrades our discourse, we should meet this moment by elevating it.

During his inaugural address, Dowd urged the student body to engage in “thoughtful, constructive conversations across differences.”

In an interview with The Observer last semester, Dowd worried that political polarization was leading to unproductive silos.

“We need to be willing to move beyond our comfort zones,” he said. “[If] we’re only relating with people who are like us, first of all, we’re inhibiting our own growth as human beings. And secondly, we’re not building the kind of community that I think we need to have here at Notre Dame.”

This is a test of that principle. If the University is sincere in its commitment to foster dialogue and debate, then it should not be afraid to invite the president to speak. Even if a majority of the campus may disagree with the president, the ability to listen to and respectfully engage in dialogue with those whom you disagree with ought to be a skill that all students have gained in their four years at this University. If it is not, then perhaps the University has not done its job.

The Notre Dame administration should not retreat into fear or timidity, but should stand boldly in favor of dialogue and tradition. Ultimately, hosting the president of the United States as our commencement speaker would be an experience no graduate would ever forget.

Many of Notre Dame’s 2024 graduates were frustrated with the choice to have retiring University President Fr. John Jenkins as the keynote speaker for their commencement ceremony. In fact, three of the four most recent keynote speakers have been directly affiliated with the University. It is almost as if the board of trustees glanced around the Main Building and thrust the first person they found onto the stage at Notre Dame Stadium.

As one of this country’s greatest universities, we should not pick underwhelming speakers simply because they are uncontroversial in the national discourse, as we’ve tended to do recently. President Trump would be a break from mediocrity. Whether this is a good or bad break is up to the individuals in attendance. But no other speaker would so forcefully reaffirm the University’s stature, its confidence and its willingness to engage with the most powerful office in the land. The 2025 graduates deserve nothing less.

If the University does not invite President Trump to speak, then it will be forfeiting a storied tradition that has exemplified Notre Dame’s commitment to civic duty. No other private university, not Harvard, nor Yale, has had the distinction of having so many presidents speak at commencement. As commencement draws near, the University would do well to ask itself whether it wishes to do away with this unique privilege, or if it will stand firm for civic duty and tradition, no matter who holds the office of president.

Notre Dame has never been a place for intellectual cowardice. It should not start now.