Walking with Kaveh in the rain, I couldn’t help but think about death. The raindrops were fat and wilting, like a plastic bag sagging with pennies. He was running late, and we weren’t expecting the storm. Neither of us had packed umbrellas. I asked Kaveh what time he had gotten up that morning, and he told me he hadn’t gotten up at all. “Today is yesterday,” he said. He’d taken a red-eye from Sacramento and had not slept since reaching Indiana.

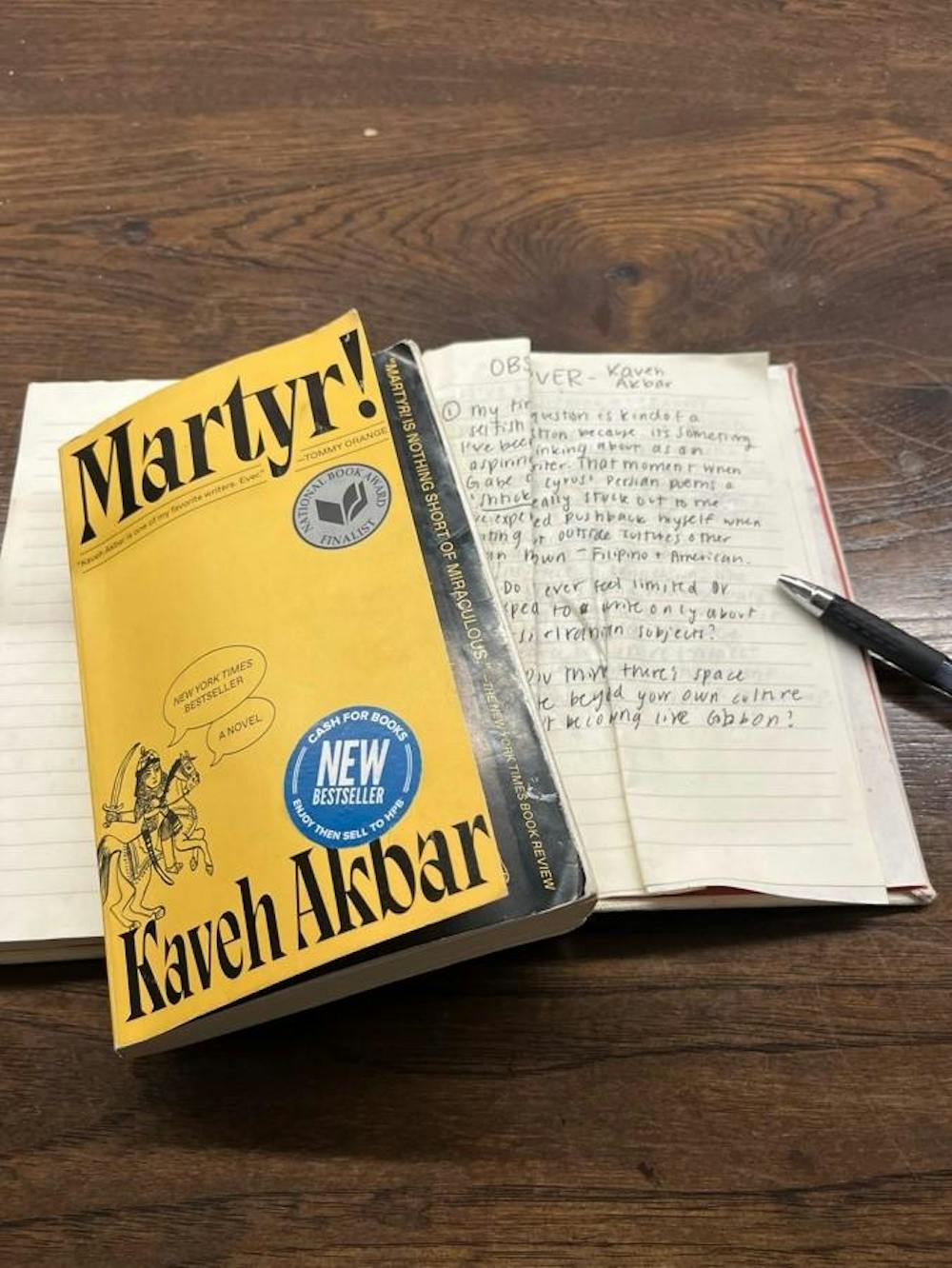

It is not every day that you get to share a storm cloud with the author of your favorite book. But at my side, there Kaveh Akbar stood, twice my height, limber as a grasshopper’s legs. Brought to Notre Dame as a part of the Literatures of Annihilation, Exile and Resistance series, Kaveh had just completed a reading of his debut novel, “Martyr!,” and now took to the rain with me. As he waited for the car that would cart him to dinner, we settled beneath the archway of the Morris Inn, both of us thoroughly sodden. I asked him my silly questions, which I would print in a silly little student newspaper, painfully aware of the fact that he’d been asked those same questions a million times before and probably a dozen times since yesterday (today).

By the time he got into the car, we were both still sopping wet but smiling. He called me his “new friend,” and I flushed with pride. I confessed I’d read his book twice the week before — once on Tuesday, then again on Wednesday. He replied, “So we’ve spent a lot of time together!” I laughed and agreed that we had, even though the voice memo recording our conversation told me that, in total, our interview was a fleeting eight minutes long.

In those eight minutes, I asked Kaveh about his book, his addiction, his thoughts on heaven and his thoughts on hell too.

“I’ve been thinking a lot about the death effect,” I told Kaveh. Because “Martyr!” is a book that’s all about mortality, and yet it encapsulates the intricacies of life in a way I have never read before. Protagonist Cyrus Shams is obsessed with dying, constantly pondering when his time will come and if he should bring it about himself. Cyrus — a poet and an addict — meets Orkideh, a terminally ill artist whose final creative act is to put herself on display in a museum in New York, allowing anyone to come speak to her.

While reading, I wondered why Orkideh’s visitors were so fascinated by her story. What makes a dying, starved artist so much more attractive than a living, well-nourished one? Why do we, as humans, all have a little bit of an obsession with death?

When Kafka kicked the bucket in a hospital outside of Vienna, no one cared that he’d written a story about a dude who woke up as a giant bug. No one knew that he’d coined a genre of surrealism that would eventually be named after him. In life, Franz Kafka was antisocial and severely miserable. In death, he is worshipped like a god.

Vincent Van Gough, Emily Dickinson and Galileo Galilei all suffered from the same cruel fate as Kafka — posthumous fame. “The death effect.” We only care about their brilliance now that they’re pushing up daisies.

“Martyr!” opens with an epigraph by Clarice Lispector: “My God, I just remembered that we die.” Death is impossible and impermeable. Earlier in the evening, in front of a room full of admirers, Kaveh said, “Just when we figure everything out, time’s up.”

If our mistreatment of Kafka proves anything, it is that we humans have a tendency to be unpunctual, to appreciate things when they’re already gone. In the most perfunctory sense of the term, as a second-semester senior, I feel like I’m experiencing something like “the death effect” myself. As my time on campus dwindles, I’ve just begun seeing everything with a newfound clarity.

It is one of life’s greatest tragedies that we are always a little bit too late. We learn to love sleep when we’ve outgrown our nap time schedule. We become grateful for the quality of our academic lectures only when we’re nearing graduation. And after all those years of yearning for more free time, at the end of our lives, we’re given much too much of it when we can least enjoy it.

Thinking about our lack of time (and our misuse of it) can become depressing. But despite the novel’s funereal title, “Martyr!” closes with a hopeful completion of Lispector’s quote: “My God, I just remembered that we die. But — but me too?! Don’t forget that for now, it’s strawberry season.”

Kaveh’s novel is more than just a commentary on life’s ending. Above all else, I think “Martyr!” revolves around the small moments in life’s middle. Fleeting yet beautiful interactions between characters prove why, day in and day out, humans continue to live despite knowing they will die.

The sky was brooding, still pelting us with droplets. We walked faster now, and the bottom of my jeans was caught in huge, black puddles. My notebook was soaked to the spine, the questions I’d carefully and eagerly composed now dripping down the page like melted Crayolas.

In response to my question about “the death effect,” Kaveh told me that he thinks that the big, eclipsing badnesses around us seem like they need big, eclipsing, monolithic goodnesses. “But my experience of life on the planet has been one where the goodnesses that have been made available to me are small and fond and local,” he said. “Here I am, talking with my new friend Gracie, and I’m going to go to dinner with my new friend Azareen and these kinds of interpersonal connections are what make the world habitable.”

Kaveh has found a cure for the death effect: relationships and gratitude. We can’t prolong our appreciation of people and experiences until after they’re gone. By then, our enjoyment is merely retrospective. Consider Vincent Van Gough’s left ear, Emily Dickinson’s rhyme, Galileo’s moons and Kafka’s bloodied kerchief — each a symbol of someone we disregarded too soon. We must recognize brilliance while it’s alive, not wait until it’s buried. There is brilliance all around us, even when our deaths seem so imminent and insignificant. There are still strawberries to eat, new friends to make and conversations to be had under shared storm clouds.

After Kaveh had driven away, the rain still fell in sloping slices like a forward slash mark. I walked back across campus alone until I heard a voice calling after me. “Come quick!” she shouted. A professor, offering me her umbrella to huddle under.

Gracie Eppler is a senior business analytics and English major from St. Louis, MO. Her three top three things ever to exist are '70’s music, Nutella and Smith Studio 3, where she can be found dancing. You can reach her at geppler@nd.edu.