Within days of the start of fall semester, a COVID-19 outbreak among Notre Dame students caused a two-week shutdown. Students once again have returned after a 10-week break to begin classes, this time to a University with immediate pre-matriculation and once-a-week surveillance testing.

Dr. Mark Fox, deputy health officer for St. Joseph County and COVID-19 response advisor to Notre Dame, told The Observer there is a risk posed by the return of Notre Dame students to the South Bend and greater St. Joseph County areas, but not to a degree of great alarm. He also opposed the conclusion found by a recent study which concluded Notre Dame’s initial August outbreak was a potential superspreader event.

The study concluded a potential correlation between Notre Dame and cases in the wider South Bend and St. Joseph County. During the fall semester, 14.5% of Notre Dame students were infected with COVID-19 and the infection rate in St. Joseph County was 7.8%, compared to the Indiana infection rate of 6.5% and national average, at the time, of 5.3%. The study published by Stanford University on Jan. 13 also concluded out of 30 universities studied, Notre Dame had the worst COVID-19 outbreak in the fall.

Fox said he was unable to duplicate the report findings as they applied to St. Joseph County and Notre Dame, WSBT reported.

Fox said after the initial return of Notre Dame students in the first few weeks of the fall semester, he found a 38% increase in cases in St. Joseph County. However, Fox told The Observer that St. Joseph County includes Notre Dame COVID-19 cases in its count. After the outbreak, the county quickly recovered to “pre-Notre Dame baseline” in less than a month.

WSBT reported Notre Dame Vice President Paul Browne said, “Dr. Fox said that if Note Dame was a superspreader, he would have expected to see a decline in the county after students left for their extended winter break. Instead, there was an increase.”

Fox said the dramatic decrease of cases in the county after the outbreak was largely due to the response by the University.

Notre Dame professor and Eck Institute for Global Health Faculty member Dr. Alex Perkins also refuted the findings of “superspreader potential” in the Stanford study. Perkins is familiar with about four other studies which have tried to connect campus and local community spread and does not find any of them particularly convincing, he said.

Perkins, who specializes in infectious disease dynamics, also noted how St. Joseph County counts Notre Dame’s COVID-19 cases into its figures and said this discrepancy could be the case with other institutions in similar surveys as well.

“That alone is already a major issue,” Perkins said.

He continued that any problem with the studies is the variety of reasons community transmission occurs, such as lifted restrictions and reopenings in some localities rather than in others.

Additionally, Fox said there is no current contact tracing nor sequencing methods to trace exact strains of transmission from Notre Dame students to the community.

“But because the county numbers overall recovered to their premium Notre Dame return baseline in that same time period [in the fall], it seemed like there was relatively little spillover from the campus,” Fox said.

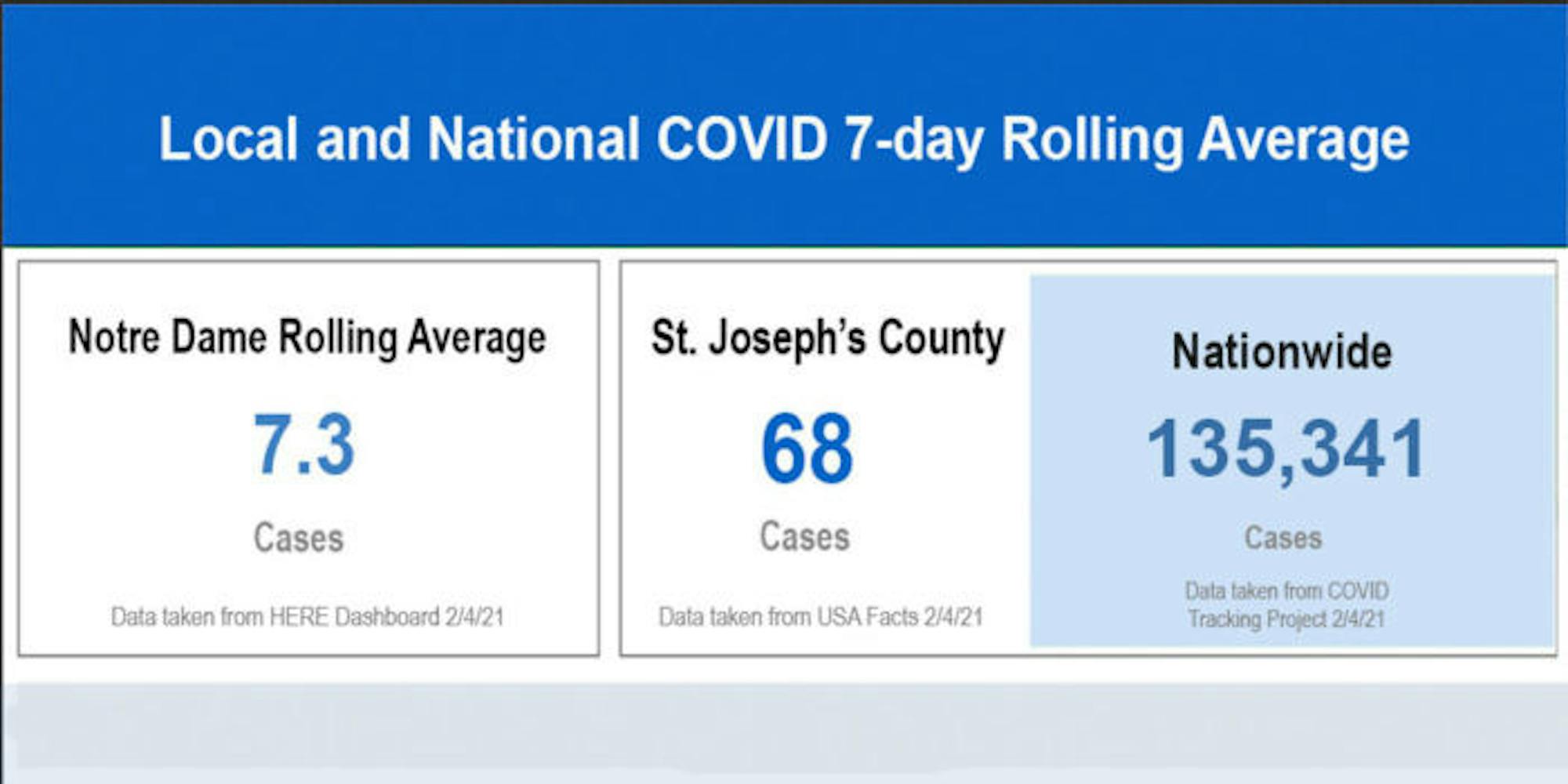

Currently, the seven-day rolling average of cases and hospitalizations in St. Joseph County has been as low as it has been since September, according to Fox.

In regards to the spring semester, Fox was more concerned with possible transmission and introduction of the newer and more contagious variants of the virus — such as the U.K. variant B.1.1.7 — as opposed to the fall semester when the University was concerned with students traveling from hotspots of virus contaminant. The COVID-19 variants have not been identified in St. Joseph County.

The Notre Dame saliva lab is able to identify the specific U.K. variant, which is the most prevalent in the U.S., Fox said.

“For the U.K. variants, there’s one genetic marker that drops out,” he said. “Somebody who’s positive with the U.K. variant will still show up as positive, but one marker will be missing.”

Concerning the once-a-week mandatory surveillance testing, Fox said the University is in a different place than it was at the start of the fall semester.

“I think [the surveillance testing] puts the University community and then by extension the county in a very different place,” he said.

Fox continued to stress the risk of transmission that comes with congregate living environments, especially since college students are often asymptomatic.

“Surveillance testing once a week is a dramatic improvement, and yet someone still could be infected, between their surveillance tests … you can do a lot of damage in that time frame,” he said.

Perkins said there is a connection between the responsibility of students in relation to COVID transmission into the surrounding county, but said there is currently nothing other than isolated incidents of this situation.

“I do think what happens on the campus has consequences for the community,” Perkins said. “I’m just skeptical of studies that have tried to pin the blame on universities as sort of being the major cause.”

Fox expects an initial rise in University COVID-19 cases because of the nature of congregate living, but he said the surveillance testing positions the University differently than in August.

Fox went on to say even though many Notre Dame students were infected with the virus last semester, it is yet unknown how long immunity lasts, especially in younger populations.

“The bottom line is, in really significant ways, the students have control over their destiny,” Fox said. “I hope that students recognize that they’re the biggest driver in terms of campus transmission dynamics, and their behavior and decisions have the biggest impact on that. To preserve that semester, graduation in-person and things like that, students play the biggest role.”

Notre Dame junior Cole Carpenter expressed concern over the behavior of college students returning to live together.

Carpenter, a New York state native, was a public health assistant over the winter session in Warren County, N.Y. and worked as a contact tracer and COVID-19 investigator.

Carpenter said the biggest increase in COVID-19 cases in his home county was during the holiday season, consequently also during the time many college students returned home.

Last semester, Carpenter said he observed a direct relation between students’ actions and the level of messaging and steps to mitigate the virus from the administration.

“I think when we first returned to campus, there wasn’t as much … strictness and that led to our first outbreak,” he said. “Then I think, once we got that scaled back down, and some of the restrictions were lifted again, I think that led to our second outbreak.”

Carpenter was also pleased to see the newly implemented surveillance testing.

“I think the stance the University is taking now is more proactive both in case management and case identification as well,” Carpenter said.

While he understood the motivation for the new Campus Compact, Carpenter was skeptical of its effectiveness.

“I think that students are still going to go to bars, I think students are still going to go to restaurants,” he said.

He continued to say the status quo of student culture and University standards were set last fall and it might not be enough to prevent another outbreak.

“I’m hesitant to believe that it’ll be enough to curb a similar trajectory in the spring,” he said. “I’m hopeful but we will have to wait and see.”

Experts say University protocols lessen potential for COVID-19 outbreak

Elaine Park

Elaine Park